The Views Are What Really Matters

If the plans materialise, the new business district on Makasiiniranta will become part of Helsinki’s national landscape during the 2030s. Architect Mikko Summanen considers its design a “once in a lifetime” project.

“I like the Finnish word suunnitella [to plan, to design]. Because we are dealing with directions [suunnat] here.”

In his office’s conference room, Mikko Summanen, architect and partner at K2S Architects, presents plans of the new buildings that will be constructed on Makasiiniranta. Makasiiniranta is part of the western side of Helsinki’s South Harbour.

“It’s not inconsequential that, for example, the alley is specifically oriented that way, because it opens a view in the direction of the Uspenski Cathedral. The principle is the same as, for example, along Unioninkatu, where Kallio Church is at one end and the Tähtitorninvuori Observatory at the other. Although this is new urban planning, it uses old, proven principles.”

The planning process for the South Harbour took a step forward in December when the Urban Environment Committee approved the draft local detailed plan for Makasiiniranta and Olympiaranta. It is based on the proposal called Saaret that won the quality and concept competition for the design of the area in 2021–2022, and was designed by a joint team consisting of K2S, the Swedish office White Arkitekter, the Sweden-based real estate investment company Niam, and the multinational planning consultancy Ramboll. Summanen is the head of the planning team.

Saaret and the resulting draft local detailed plan comprises four new buildings, which will accommodate offices and hotel facilities, as well as restaurants, cafés and other commercial spaces at street level.

Landscape design and green elements play an important role in the plan, says Summanen. The buildings will have green roofs, and parts of the ground area will be left unpaved. This will delay stormwater runoff and bring built nature to the area, which is currently just asphalt and parking lots.

“Green will flow like small streams or branches from Tähtitorninvuori down to the waterfront. Closest to the sea will be low-lying archipelago vegetation that will not obscure the views of the opposite shore”, describes Summanen.

For the same reason, the four buildings in the Saaret proposal are low in height: they leave space, on the one hand, for the greenery of Tähtitorninvuori and, on the other hand, for the new museum of architecture and design, explains Summanen.

“This is a very sensitive location, a national landscape when viewed both from the sea and from the other direction, from Tähtitorninvuori. Views from the hill were already taken into consideration at the time when Tähtitorninpuisto was planned.”

“Although this is new urban planning, it uses old, proven principles.”

The observatory designed by C.L. Engel was completed on Tähtitorninvuori in 1834, and the park around it in the early 20th century. The design of Makasiiniranta must also take into account the Suomenlinna World Heritage Site, as it is located in its buffer zone and the larger landscape.

When approving the draft local detailed plan, however, the Urban Environment Committee hoped that an increase in the height differences between new buildings would be explored.

According to Summanen, the place cannot withstand very tall construction, due already to the valuable views. The current “very restrained horizontal appearance” is based on the city’s own planning principles and the competition programme in turn is based on them, offers Summanen in justification.

“We are currently examining a small variance in the heights of the buildings. There’s probably nothing dramatic to be expected, more like fine-tuning.”

Two Museums

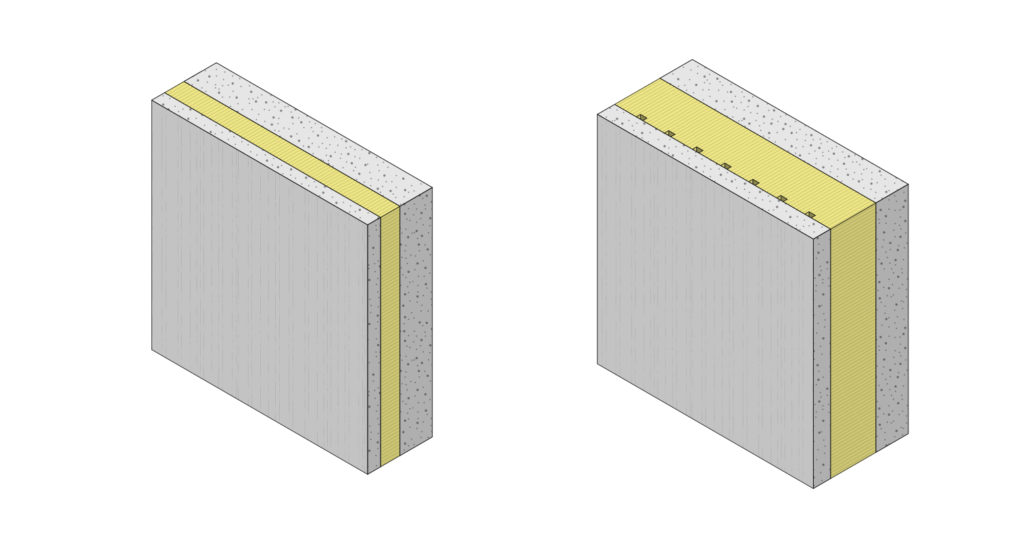

One factor that guided the design process has been sustainability, says Summanen.

“We are trying to use as low-carbon building materials as possible, such as wood. We are currently investigating the use of renewable energy in the area, possibly geothermal energy.”

Long-term conversion flexibility has also been given attention. The buildings are designed so that they can be converted from a hotel to offices or vice versa, for example.

Part of the sustainability thinking involves the reuse of existing buildings in the area, that is, Port House and the Olympic Terminal completed in the early 1950s, once regular ferry traffic to Tallinn and Stockholm moves away from the port.

The Helsinki Art Museum is currently looking for new exhibition spaces, and the port buildings are strong candidates.

“Port House was originally a tall, imposing warehouse space with beautiful cast-in-situ concrete structures. Later it was converted into offices and new mezzanine floors were inserted. Just by dismantling these low mezzanine floors, you would get a promising embryo of an exhibition space that can be refined into an exciting whole.”

Summanen says that in stage one of the Saaret group’s competition proposal, they proposed buildings for the new museum of architecture and design.

“At the time, I thought, and I still think, that it would have been a sustainable solution for this time and in terms of the future. But I also understand the reasons why it was not possible.”

The main reason was the schedule, says Summanen. The vacating of Port House and the Olympic Terminal depends on the transfer of port operations, which will possibly take place in the early 2030s, but there are still many uncertainties. The aim is to open the new museum of architecture and design to the public as early as 2030.

Makasiiniranta is planned to be built in stages, with the two northernmost buildings of the Saaret proposal to be completed first in 2029–2030, and the two buildings located closer to the ship terminals later in the 2030s.

The Museum of Architecture and Design is about to get a new building in the area located between the Saaret proposal’s commercial district and the Old Market Hall, but so far, its place in the draft local detailed plan is just empty space. The five proposals that made it to stage 2 of the museum’s architectural competition were announced at the end of December, but the winner will not be announced until next autumn.

The museum project has, nevertheless, from the very beginning influenced the design of the commercial blocks. In Summanen’s opinion, they must not draw too much attention away from the future museum building.

“I think the museum should be dominant in this building frontage. Saaret is not a special public building in the same way, but rather four blocks that accompany the museum.”

Once in a Lifetime

The practical architectural design work for Makasiiniranta, according to Summanen, is being carried out in collaboration between K2S and White Arkitekter as an equal team effort. Other design work, such as the structures, traffic and technical installations, is provided by Ramboll.

White Arkitekter has been a familiar partner for K2S already from the time of the renovation and extension of the Helsinki Olympic Stadium in 2013–2020, says Summanen.

“Fredrik Källström was involved in the project as an expert consultant; they had just completed the Tele2 Arena in Stockholm. Our cooperation went so well that we invited them to join us when the Makasiiniranta competition team was being put together.”

For Summanen, the design of Makasiiniranta has been one of his main projects already for several years.

“I have felt that this is a project full of responsibility yet nevertheless truly inspiring. This is, on the one hand, virgin new construction that is committed to the old historical city centre, harbour architecture and railway tunnels, and, on the other hand, a combination of architecture and landscape architecture, where the old, beautiful Tähtitorninpuisto slides down to become part of a new landscape. All the elements of urban planning are present within a small area.”

“I have to say, this is one of those once-in-a-lifetime projects.”

Discussion About the Competition

The Saaret project is being financed and implemented by Niam, a real estate investment company with a Swedish background. Summanen says that he has been following the recent public discussion about the role of real-estate investors in urban development.

“In urban planning, different parties have different roles, which can also be criticized. I think, however, that the design of Makasiiniranta is fairly conventional urban development, and the city’s steering role is rather strong here. I also think that there is no such pursuit of hyper building density, that real-estate investors are sometimes criticized for. And, of course, it is always someone that has to pay for the construction,” reflects Summanen.

The Finnish Association of Architects (Safa) did not participate in the competition for the design of Makasiiniranta. Safa would have wished for an open architectural competition for the design of this valuable area, so that as many diverse proposals as possible would have been obtained.

In Summanen’s opinion, Safa should nevertheless have been involved in the competition.

“Even if Safa at times would have disagreed with the organisers about the competition’s framework, when it comes to such central locations as Makasiiniranta or even Elielinaukio, I think it would be important that Safa’s voice be heard on the competition jury. ”

“And Safa has been quite ambitious in developing the competition system, which is a good thing,” adds Summanen.

“It was not a free pass for real-estate investors.”

The current Chairman of Safa, Asko Takala, was not involved in making the decision whether or not to participate in the competition, but notes that it is good to have a public discussion about the competition principles and how they fit with Safa’s values. For example, if economic factors are strongly emphasized, there may be a fear that architectural design will come second in the evaluation.

“We are happy to offer our expertise to various competitions and we constantly strive to find ways to be involved in them. On the other hand, it is also important that the central principles of architecture competitions are adhered to,” says Takala.

The City of Helsinki’s urban planning of the South Harbour is led by Salla Hoppu, manager of the city centre team. According to Hoppu, the competition format was chosen because they wanted to find a plan that could actually be implemented, as well as a developer who was committed to the project from the start.

“The city has been trying to develop the South Harbour for years through traditional architectural competitions. Competitions have been organised for, among others, the Armi Centre, the Guggenheim Helsinki and an ideas competition for developing the urban structure of the South Harbour area. None of these have led to any implementations.”

Although the Makasiiniranta competition was aimed at developers rather than architects, the evaluation criteria were based on the planning principles and the quality of architecture defined by the urban planning, says Hoppu.

“It was not a free pass for real-estate investors. The planning principles themselves pay a lot of attention to the cityscape, the height of buildings and the valuable views. The starting point in the planning of the South Harbour is its status as a national landscape.”

Public Urban Space

Now that the draft local detailed plan has been approved, the next step is to make a plan proposal.

The plan is being prepared as a partnership plan. In addition to the City of Helsinki’s urban planning department, the designers of the Saaret group and the real-estate developer Niam, also involved in the preparation of the plan are the museum of architecture and design project representatives as well as the Port of Helsinki, which will continue to operate in the area. According to the current plan, international cruise ships will continue to stop at Makasiiniranta during the summer, even though scheduled service traffic will be transferred elsewhere.

Preparing a local detailed plan together with private partners is a normal practice in Helsinki, says Hoppu.

“Most of the plots in the centre of Helsinki are privately owned land. In that case, the local detailed plans are prepared as partnership planning together with the landowner and the projects.”

Partnership planning is not exceptional on the city’s own land either, says Hoppu. For example, several blocks in Kalasatama have been planned in this way.

Makasiiniranta is city-owned land, but according to the competition brief, it can later be sold to the project developer, that is, to Niam.

“They have a purchase option, but a separate decision must be made about the sale. It is by no means certain that the land will be sold,” clarifies Hoppu.

The Saaret plan has also been criticized for not including any housing, which is why some have feared that the area will become too quiet in the evenings.

Hoppu believes that there is no need to worry about this.

“Vitality at different times of the day and year has been considered in the design process. Makasiiniranta is surrounded by the residential districts of Ullanlinna, Kaartinkaupunki and Kaivopuisto, and in addition, a hotel, the new museum of architecture and design, as well as cultural and restaurant activities are coming to the area. Housing does not mix very well with sidewalk bars that are open late, because experience has shown that Helsinki residents crave peace for their residential environment.”

The starting point for the development of Makasiiniranta has, from the beginning, been that it is a public, inner-city-type space, says Hoppu. A key aspect of the planning of the area, in addition to cityscape factors, is to open up the closed waterfront – which currently serves as the harbour’s parking lot – to all the city’s inhabitants.

“This is the missing piece of the coastal route that encircles the cape of Helsinki, connecting the Market Square to Kaivopuisto park.”

“This is the missing piece of the coastal route that encircles the cape of Helsinki.”

Infill Construction on the Katajanokka Waterfront

The South Harbour area also includes the Katajanokka waterfront on the opposite bank to Makasiiniranta, which is being developed at the same time.

The Allas Pool, a seaside spa located on the waterfront, has received a plot reservation. Its current buildings are temporary and will soon reach the end of their useful life, and there are shortcomings, for instance, in flood protection and the condition of the harbour walls, says Hoppu.

A precondition for the plot reservation is that an architectural competition must be held for the design of the new spa building, most likely already this year. The planning principles also propose a public walkway to the waterfront and the conversion of Katajanokanlaituri into a boulevard. Additional construction is also planned along the street.

“But the height and amount of construction will be limited, so that it is low and fits in with the milieu of the Market Square.”

Apart from the temporary structures currently located in the area, such as the sea spa and the ferris wheel, nothing is planned to be demolished to make way for new construction, says Hoppu. ↙