Open the Box!

The Finnish Architectural Review has followed theatre construction since the early years of our publication, writes Editor-in-Chief Kristo Vesikansa. Instead of the generic facilities provided by the black box, many of today’s theatre-makers are intrigued by staging performances in other existing spaces, which then become an integral element of the dramatic piece itself.

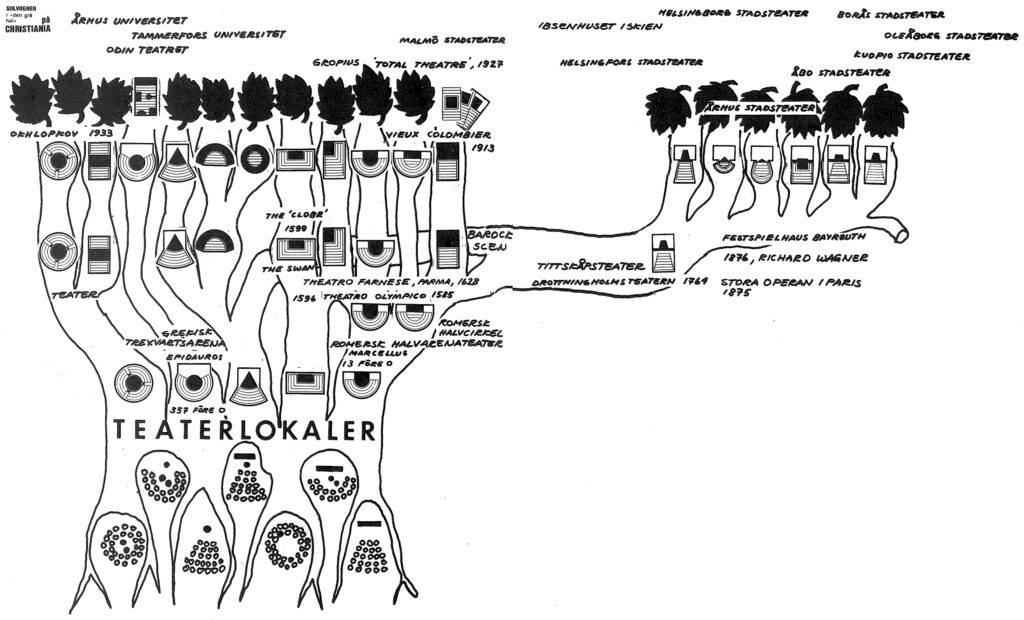

Out of all our cultural institutions, the theatre most likely has the strongest architectural traditions. It established its customary form in ancient Greece, while the most influential of the later interpretations has been the so-called “diorama theatre” developed in the Baroque era. Original theatre typologies have also been created outside the Western sphere, such as the Japanese Nō theatre with its pavilion-like stage.

The Finnish Architectural Review has followed theatre construction since the early years of our publication. The specialty was afforded particular attention in the 1960s–1980s, when the nationwide network of local city theatres grew into its current scope with support from the state government. For architects, theatres offered a rare opportunity to create monumental works that elevated art beyond the mundane existence. The result was several outstanding works of architecture, such as the Helsinki City Theatre by Timo Penttilä, which was featured in our special issue 10–11/1967 that was dedicated to theatre architecture.

Young architects who were inspired by contemporary theatre, however, viewed city theatres as monuments to a dusty old elite culture. Sakari Laitinen captured the sentiment in his editorial for the 1967 theatre issue: “The most important task of architecture, now and in the future, is to attempt to solve the problem of large numbers. This means that the main aim of theatre planning must be to increase variety, tolerance and flexibility to counterbalance the one-sided, rigid monumental theatre.” The time was ripe for a new type of theatre to emerge.

The modern alternative has since been named the “black box”. The goal was to create a space that would be as neutral and versatile as possible and would easily transform to suit the needs of varied performances, thus reaching new theatre audiences. The space did not need to be wrapped up in a monumental frame, but would rather position itself as a natural part of the existing urban fabric, as one public service among all the others. Over the last fifty-odd years, this radical spatial concept has established itself as the norm for theatres and other performance venues. In fact, no free-standing theatre buildings have been constructed in Finland since the 1980s, as new performance spaces have been integrated into multipurpose cultural centres – and, in Lappeenranta, even within a shopping centre.

One of the leading proponents of the new type of theatre building was architect Pentti Piha, whose work and activities are examined in this instalment of our journal by Kaisa Karvinen. Overall, Karvinen has played an important role in developing the theme and content of this issue. The various dimensions of the black box are also reviewed in other articles: Venla Kotilainen and Heini Hermunen, for instance, reflect on the limitations imposed by its ostensible neutrality from the perspective of social accessibility.

Over the last fifty-odd years, this radical spatial concept has established itself as the norm for theatres and other performance venues.

Instead of the generic facilities provided by the black box, many of today’s theatre-makers are intrigued by staging performances in other existing spaces, which then become an integral element of the dramatic piece itself. The chosen venue is typically a vacant, condemned building, which entails that the performance inevitably takes a stand on the current issues of protecting and demolishing buildings. Dramaturge Henriikka Himma contemplates these themes through the lens of two of her recent, place-bound productions.

Modern cinemas are also black boxes of sorts, intended to protect the illusion of the viewing experience by hiding both the spatial framework and the necessary audiovisual technology. In his piece, Jaakko Karhunen writes about the counter reaction to this type of theatre design, describing the nostalgia for the disappearing projectors and other equipment, which can be sensed particularly in the temporary viewing venues of film festivals.

Another type of contemporary stage is represented by multipurpose arenas that serve the purposes of sports, concerts and other events. Over the last fifteen years, they have become a key component of ambitious development projects involving our city centres, and the plans are often driven by construction companies and property investors. Tommy Lindgren writes about the type of urban environment that has been or is being created based on this premise in four large Finnish cities.

The current issue also introduces three recent projects built in the service of theatre, events and sports. The 1950s Small Stage at the Finnish National Theatre has been renovated with reverence to the original architecture, and former auxiliary rooms have been converted into new types of performance spaces. The Event Centre Satama in Kotka is an archetypical black box that facilitates a multitude of events, with architecture that draws inspiration from the grand scale and rugged image of the harbour area. Finally, the Tammela Stadium in Tampere demonstrates that the increasingly popular hybrid model of development – the construction of the football stadium was financed by integrating housing and commercial premises into the project – can be applied to create impressive architecture and to reconcile a fragmented cityscape, provided that the volume of construction is in proportion to its environment. ↙