A Recipe for Sustainable Construction

The log row house in the wooden residential district of Honkasuo aims to be an example of how to build as sustainably as possible. Is it enough?

For the last twenty years, densely built urban neighbourhoods of low-rise timber construction in Finland have been inspired by the milieu and scale of historical wooden towns, so it was about time for the field to welcome some new applications for the method of construction in such areas.

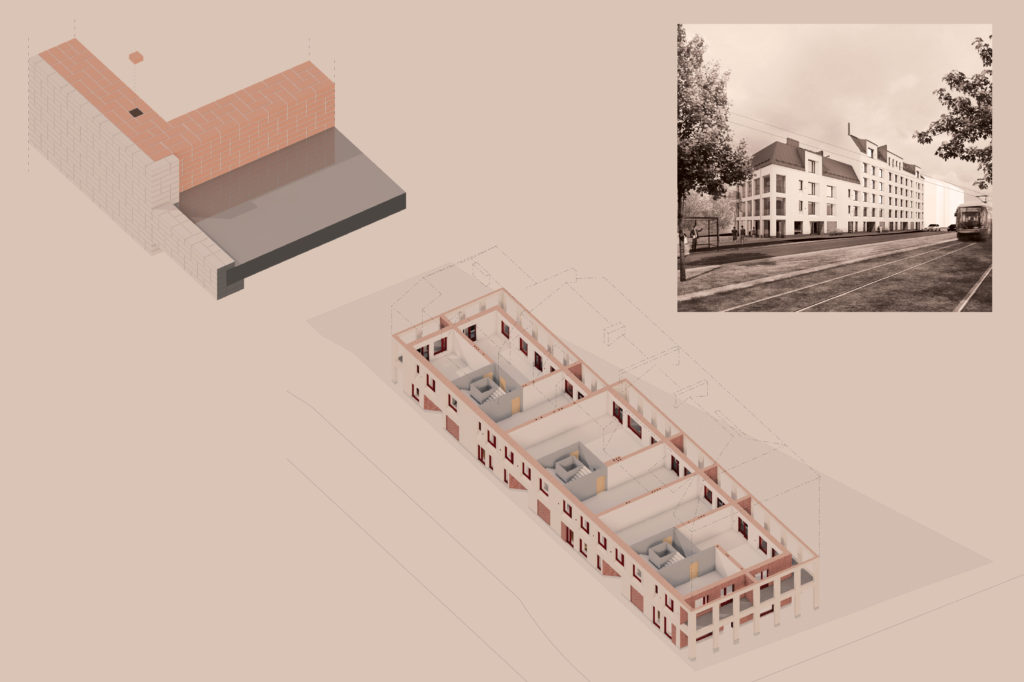

One is found in Helsinki’s Honkasuo, at the edge of the “wooden eco-district” planned for 1,500 residents: a sweeping row house of seven linked units built from hand-carved logs. It is as if an 18th-century carpenter had hand-crafted a stretch of Portobello Road townhouses in a modern-day suburb.

Behind the project, entitled Log Row House Aarre (i.e. “treasure”), is a classic tale of heroism in which an underdog defies the odds and goes to battle for a better world. Faced with the climate crisis, architect Minna Aarnio and construction engineer Jukka Reinikainen had an epiphany on the destructiveness of their field and decided to take concrete action to enact positive change – they decided to design and develop a project to show others that it is already possible to build in a more sustainable manner.

The timber was felled in a forest in Ähtäri, and the project employed Finnish log-hewing knowhow. Each unit in the building is comprised of its own 8.2-by-8.2-metre log frame. One side is slightly shorter in order to create the curved shape specified in the detailed plan. As with log buildings in general, this construction can also be moved in time to another location, and the modules can be reassembled in a different configuration, should the need arise.

Log Row House Aarre

Rakennusasiaintoimisto Aarre / Minna Aarnio

LPV architects / Tarmo Peltonen, Rosa Paukio

Location Haapaperhosentie 27 / Leirikuja 4, Helsinki

Gross Area 907 m2

Completion 2023

More photos and drawings of the project →

For Aarnio, the project revealed that sustainable building practices are only now just taking shape, which added to the designers’ workload during many stages of the project. For example, the use of renovated windows in the outbuildings was initially ruled out due to the lack of CE marking and required an extra round of statements by an expert in building product approval.

“At the same time, we have paved the way for others, and this will hopefully make it all easier for the next ones to brave a similar venture”, says Aarnio. The Ministry of the Environment has, in fact, since adjusted their stance on recycled building components.

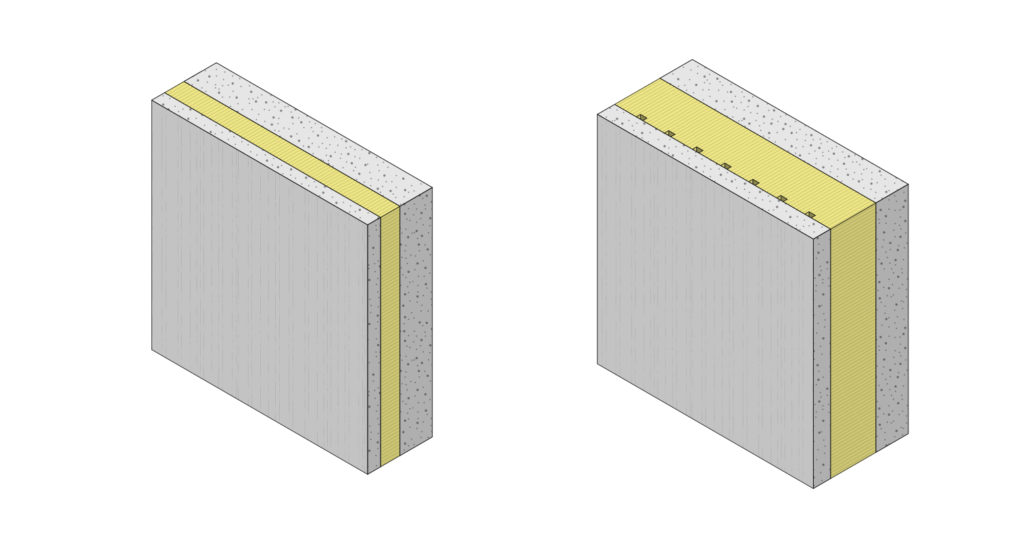

Another example of facing ossified attitudes is that, while Honkasuo is profiled as an area for timber construction, logs were not immediately accepted as an exterior finish. However, weatherboarding would have prevented the storage of heat from the sun into the log frame, which, in turn, would have lowered the energy rating from the highest class. This was what finally changed the official’s mind.

“Weatherboarding can always be added at a later date, if it turns out that the sun beats down too hotly on any given spot. That’s what builders used to do in the old days”, Aarnio explains.

For Aarnio, architecture that is designed on the terms of sustainability boils down to what are essentially obvious and rational solutions: the angle of the roof is determined by solar panels, and the height of buildings and the positioning of windows are optimized to facilitate natural ventilation. Aarnio would have loved to leave the dovetail joints in the log structure visible, but the corner boards help to preserve the logs in good condition.

The distempered logs are paired with white-painted window frames and a sympathetic row of Falun red outbuildings and a sauna, underscoring the notion of a vernacular where the wheel does not need to be reinvented, but only put to good use – unlike a usual heroic architect would do.

Spread out over 150 years, the carbon footprint of these log-framed treasure troves is a third lower than that of a concrete building of similar size. Moreover, a log building binds five times as much carbon, and because the carbon handprint is larger than the carbon footprint, the building can be regarded as carbon-neutral, or even carbon-positive.

However, even the most environmentally-friendly construction always causes a spike in emissions. “This is the huge elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about. What is the selection of practices that we are even able to use when emissions are regulated more strictly?” Aarnio reflects.

But if we must build, doing it sustainably is, in Aarnio’s view, best achieved precisely on this scale. She would also like to see the practices trickle down, or rather up, to the construction industry and town planning at large.

Instead of the carbon calculations, the success of the Aarreaitat building will ultimately be decided by whether people will want to live in a terraced log house in Honkasuo today as well as in the 2180s. It is impossible to see the world as it will be 150 years from now. But if one looks at the kinds of constructions that have been preserved and remained in use from centuries ago to this day, the simplicity and adaptability of the Aarreaitat concept seems to be among the best guesses as to the recipe for future construction. ↙