Helsinki is a Prisoner of its Geography and Government

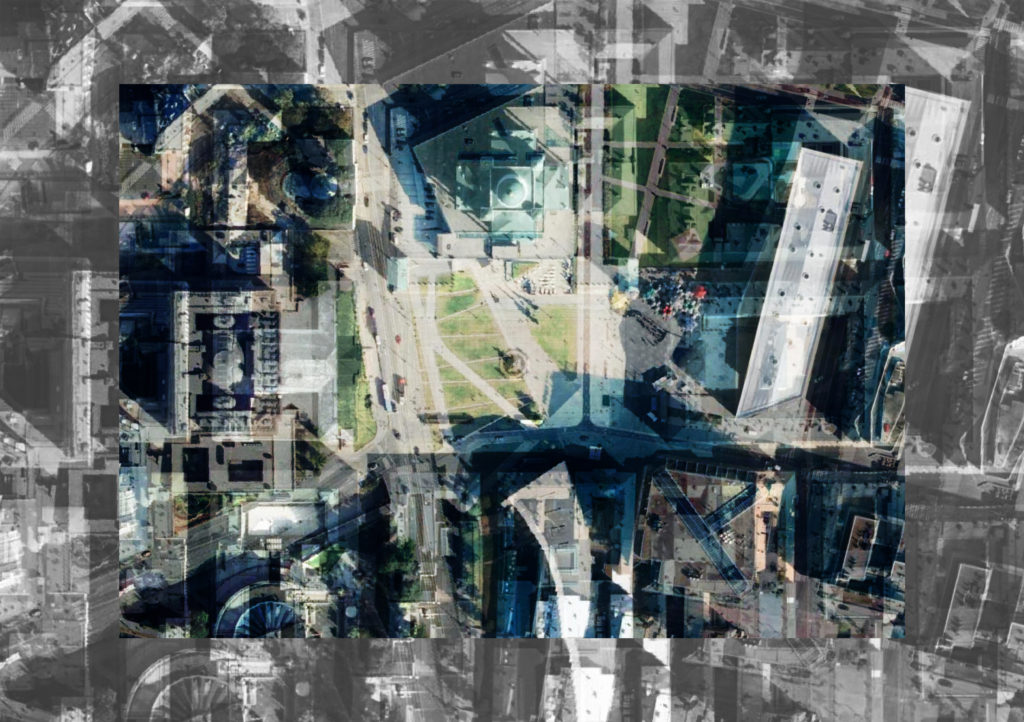

The growth of the Helsinki region is a challenge for the development of Helsinki’s city centre.

The urban development ideals that have taken over the planning in Helsinki over the last few decades have failed to recognize the nature of urbanization in the long term. In particular, perspectives arising from the sphere of urban economics have been adopted as policy on rather flimsy grounds. An example of this discourse is the so-called “urban shortage” that was heavily featured in the Helsingin Sanomat newspapersome years ago, referring to the scarceness of land area regarded as being urban in terms of its population density.1 Over the last couple of years, discussions sparked by a type of change hangover in Helsinki have revolved around the waning of the inner city. It is regrettable that the debate is dominated by abstract ideological and theoretical perspectives, even though the nature of the problem is very much concrete – geographic and geometric.

In order to understand the current development, we might look at the 1992 and 2002 master plans, which constitute a significant turning point. The former initiated the relocation of harbour functions away from the inner city, and, following international examples, the latter allocated the areas vacated as a result to housing. The latest layer in this development is represented by the City Plan 2050, a long-term strategic land use plan launched in 2013, in which Helsinki, with its “urban boulevards”, aspires to be more Continental than all the Continental European cities themselves.

Post-Blomstedt Helsinki

The physical realities of the Helsinki region are already evident in the very early metropolitan visions. In his 1915 plan for the Munkkiniemi–Haaga districts, Eliel Saarinen stated that Helsinki, which is positioned on a headland, has a relatively small amount of land area suitable for development around the city centre in comparison to the other Nordic capitals.2 However, the impact of the city’s geographic characteristics on future development was not truly recognized until the debate that followed the Pro Helsingfors plan that Saarinen and Bertel Jung drew up three years later, and the city’s first master town plan drawn up by Berndt Aminoff in 1932.3 A potent three-part series of articles by a young Pauli Blomstedt published in Arkkitehti questioned the visions of the contemporary powers that be.4

Eliel Saarinen compared the expansion possibilities of the Nordic capitals in 1915. The percentage and sector of suitable land for construction from left to right for each city: Copenhagen 228.4° (63%), Stockholm 291.5° (81%), Oslo 264.5° (74%), and Helsinki 115.7° (32%). Image: Eliel Saarinen: Munkkiniemi-Haaga ja Suur-Helsinki, 1915

In 1932, Blomstedt was ahead of his time in recognizing a shift that would not be realised in Helsinki until the period spanning from the 1960s to the 2000s. He served up his own vision with striking acuity: “Never again shall we witness the birth of the type of metropolises that exist today. Should the cities that are currently in the region of a quarter of a million inhabitants ever grow their population into the millions, their land area would correspond to that of an entire province. A future metropolis might be ‘the City’ to which people living in the country come to work during the day and to play in the evenings.”

In modern terms, Blomstedt’s view was that density and accessibility are interchangeable attributes of a metropolis. The Helsinki inner city – i.e. “the City”, as Blomsted also referred to it in Finnish – does not need to become more densely built, nor does it need to be relocated in the name of efficiency, but the historical centre can be preserved as the city centre by building onto the archipelago and the shoreline. On the other hand, suburban development (the “outer settlement” in Blomstedt’s words) that supports a smallish city centre requires an efficient and functioning transport system.

The urban planning that was implemented over the following decades primarily consisted of selected notations made as an aside to Blomstedt’s critical observations. Both of the development trends recognized by Blomstedt have been noticeable in the urban planning for the Helsinki Metropolitan Area as a continuous push and pull between the city centre and the suburban areas. Work on the regional transport system has been overshadowed by the national transport policy adopted in the 1960s, and the situation is not alleviated by the fact that public transport is being developed in an inner-city-centric fashion in accordance with the suburban transport principles created in 1926.5 The matter is also not helped by the fact that the City of Helsinki has, in its own plans, stuck to Saarinen’s and Jung’s ideal of the “little Greater Helsinki”, a metropolis that encompasses a peripheral expansion of the small inner city.

Blomstedt criticized the plans for ”little Greater Helsinki” by Eliel Saarinen, Bertel Jung, and Berndt Aminoff. On the right is his own vision of the future Helsinki region, enabled by the developments in transportation and new types of housing needs. Source: Arkkitehti 11/1932

The Challenge of a Densifying Inner City

Between 1990 and 2020, some five million square metres in gross floor area of new housing have been built in Helsinki’s inner city on land that has become available through the relocation of harbour and industrial operations. In terms of the overall volume, this ambitious urban renewal has increased the size of the inner city’s building stock by a third. However, five sixths of this growth has been directed outside of the city centre. At present, the density of central Helsinki is on a par with the other Nordic capitals. On the other hand, the population of the surrounding region is smaller than in, say, Stockholm for the simple reason that Helsinki, as a whole, is smaller.

The city’s geographic special characteristic is identifiable in the implemented fabric: a restricted historical centre and an urban fringe that spans several municipalities. If an urban economist considers Helsinki to be a puny capital, it is because of the land area and not the volume or quality of construction in the central area.6

It remains unclear, however, whether the proclaimed shortage of urban land is ultimately more problematic for the suburbia than it is for the inner city itself. The increase in travel speeds that began in the 1960s generated a rather unstructured “commuter zone” alongside the inner city, and a suburban fringe without a distinct identity came about as an inexpensive alternative for functions that spilled out of the city centre. As the suburban area grew, however, it changed the position of the inner city permanently.7 Back in the 1980s, the suburbs were still viewed to have grown on the coat-tails of the historical city, but the recent discussions on the waning of the city centre demonstrate that the inner city, as it is today, is just as much a dependant of its suburban surroundings.

Back in the 1980s, the suburbs were still viewed to have grown on the coat-tails of the historical city, but the inner city, as it is today, is just as much a dependant of its suburban surroundings.

Turning Towards the Suburbs

The transformation of inner Helsinki that started in the 1990s is now a few last districts away from completion. Even though the gross floor area of the building stock has increased during this period from 16.6 million to 21.6 million square metres, the inner city’s share of the region’s population has remained steady at around 15 percent. The inner city development has focussed strongly on housing, which is evident in the decrease in the relative proportion of overall construction volume. While the inner city building stock in the 1990s still made up a quarter of the construction in the overall metropolitan area, the current share has dropped to a fifth. As a local service, the city centre is not really functional, and the increasing housing in the centre diminishes its regional significance. This is not a problem for central living per se, but the city centre has lost its position of representing the entire metropolitan area due to the changing structure. Even with densification measures, the future fabric of the city is more loosely built than the historical centre.

In any other area of society, the selection of a non-representative fifth as the basis for policy would be regarded as objectionable idealism or populism. In Finnish urban planning, however, the way that the inner city has been built and its importance for the whole area has been taken as gospel, which is creating new, unanticipated challenges for the current development of the Helsinki Metropolitan Area. It is of note that the role of the inner city, when examined in both absolute and relative terms, continues to diminish. If the population in the Helsinki Region is to reach the declared ideal of two million, maintaining the inner city’s relative size in proportion to the overall urban area would require a 1.5-fold increase in the inner city’s building stock. In terms of construction volume, this would entail the doubling of the pre-1990s built volume, or the quadrupling of the volume of areas developed within the last 30 years. The current plans show no signs of such visions.

For some time now, the focus of development has remained outside of central Helsinki. Today, the suburban area is four times the size of the inner city when it comes to the population and three times larger when it comes to the volume of building stock. The combined population of the surrounding municipalities in the greater Helsinki Region already exceeds that of Helsinki’s inner city, and people living in this outer fringe have no need to travel to central Helsinki – with the arrival of electric cars, it would even appear to be wiser for the residents to use the services offered at the hypermarkets located along the ring road.8 It is outrageous that the outer municipalities have been left waiting for 30 years for the tramlines to reach them. The ideal in public transport plans can no longer be to find the scheme that offers the greatest capacity or simply feeds inner Helsinki, but rather to identify the mode of transport that best suits the entire landscape and the changing traffic directions. Could it be time to turn our gaze towards the suburbs and begin to view them as something that is not merely an undeveloped stage in the evolution of a historical urban ideal but as something whose existence is justified in its own right? ↙

ANSSI JOUTSINIEMI is an Associate Professor of Urban Design and Planning at the University of Oulu.