Halting New Construction – Interview with Charlotte Malterre-Barthes

The moratorium on new construction is one of the most attention-grabbing manifestos in the field of architecture in recent years. Architect Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, its initiator, explains what the initiative is actually about.

“To build is to destroy” is a quote attributed to French architect Charlotte Malterre-Barthes. With the quote she has spoken about how architecture has become detached from the material reality, and about the destructive force of construction and architecture’s complicity in it.

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is an architect, urban designer, and Assistant Professor of Architectural and Urban Design at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), where she leads a lab called RIOT, Research and Development for Innovation on Architecture, Urban Design and Territory. She is perhaps best known for launching an initiative calling for a global moratorium on new construction. The initiative calls for a stop on new construction, extraction and demolition so that the industry could realign itself to working with what already exists.

The initiative is radical, yet there is historical precedent for construction moratoriums. Moratorium is a legislative device that has been used, for example, in the context of protecting historical environments or in the case of seizing the construction of nuclear power plants. Moratoriums can be short term or indefinite.

Malterre-Barthes claims that one of the benefits of the moratorium is to make visible how much of contemporary construction is actually unnecessary. Will this render architects obsolete or can stopping construction in fact be one of the most exciting things to happen to the profession?

Matti Jänkälä: You started your initiative A Moratorium on New Construction in 2021. How did it come about?

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes: One of the very clear prompts was the Covid crisis that brought the world to a halt. Many things that were previously not considered to be stoppable stopped. But not everything stopped. Quite strikingly, construction continued on after only a few months’ pause in most parts. Many sectors underwent a longer halt resulting in great changes and reflection on their practices but construction continued with business as usual. Critical questions about the profession remained unaddressed.

Additionally, the research that I had carried out in my dissertation in ETH Zürich on commodities, food production, and commodified supply chains provided me with the theoretical background needed to articulate a reflection on the political economy of construction. Construction is never just building but it relates to larger commodity systems, extractive mechanisms, and so on.

These two issues merging are in a way the basis for a moratorium on new construction. If everything could be stopped, and we understand that construction is a part of the problem, how come it was not stopped?

MJ: What forms did your initiative take in the beginning?

CMB: Instead of it being long prepared and with a lot of background research this was about throwing the idea out there to be discussed.

The first format of the initiative were four roundtables. The first one was hosted online in Harvard where I was faculty at the time, the second one at ETH Zürich, the one in Venice, and the last one was in person at the conference Berlin Questions. The discussion format was a useful tool to debate what it actually means to stop building.

It was crucial that the discussion was not only between white academics but also with colleagues active in other parts of the world. In a way, hosting the discussions in these so-called Western knowledge-production centers was useful to spread the word and gain legitimacy. But at the same time, it was important that those participating in the debates were from around the globe in order to decenter the debate. For example, what does it mean to say to stop building in places like Egypt or India? It was really helpful to give nuance to that question.

First and foremost, the moratorium is a debate device, and I think that the fact that it first emerged as such is a testimony to it as a collective tool.

When looking at the amount of building stock that we have constructed globally, it should, theoretically, be more than enough to serve our needs.

MJ: When you started the initiative, you called it “A Global Moratorium on New Construction”. Since then, there has been discussion on the word global, and whether it should be in there or not. What role does the word global play in the moratorium and how has your thinking developed in regard to the global perspective?

CMB: At one point, there was a need to take the word global out to give the initiative more nuance and to see how it could be localized.

The first instinct was to call out the privilege of demanding a moratorium from where you are, from the perspective of the consolidated building stocks in places like Finland, France or Switzerland where there are at least theoretically more than enough buildings and infrastructure to stop construction or at least pause it.

However, interestingly enough, the need to reintroduce the word global re-emerged. When looking at the processes of housing production, for example, you could see that, even in the places where construction is claimed as an absolute necessity, the new building stock does not, in fact, go to the people who need it most. A critique emerged of the construction sector in that it is global with systems of extraction and commodity markets spanning the globe.

When looking at the amount of building stock that we have constructed globally, the amount is staggering – some 250 billion square meters. It should, theoretically, be more than enough to serve our needs. But of course, it is not about advising for relocating people, but rather looking at the mechanisms of construction, and questioning claims that we have to keep building.

So, the initiative grew in complexity and benefitted from the debates among colleagues. It also benefited from concepts such as non-extractive architecture.

MJ: The complexity is visible in the nine demands that you have attached to the call for a moratorium. The first demand is to “stop building”, but then you proceed to demands like “house everyone”, “halt extraction” and finally – “take care”. Why did you select these demands and why are they especially important to you?

CMB: I believe the demands helped to articulate the call in a more manifesto-like format. I call the moratorium in a way “clickbait”. It is supposed to be provocative and demand attention. The demands attached to the moratorium help to formulate a program, that emerged from many conversations. For example, this is why “house everyone” is the second demand – it is to establish that you don’t only call for a stop but take responsibility for providing housing for everyone. However, building new is not the only way to provide housing.

I call the moratorium in a way “clickbait”. It is supposed to be provocative and demand attention.

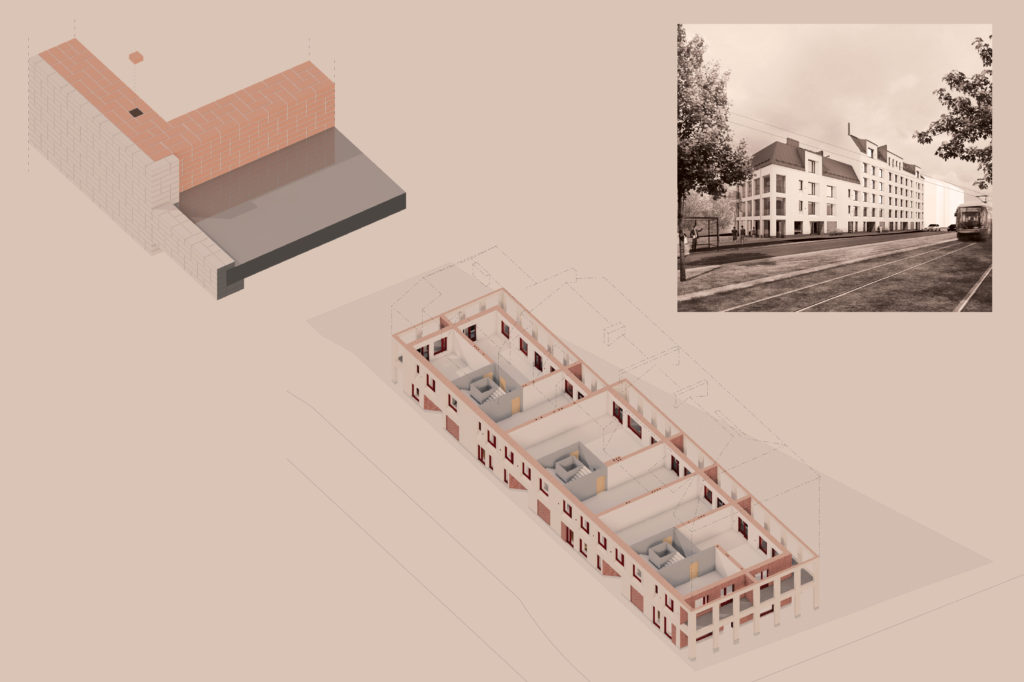

MJ: In the initiative you say that the field of construction should realign itself to work with with what already exists. What role does heritage play in your initiative?

CMB: To me, if we are serious about tackling the climate crisis, then everything is heritage. But we need to be able to work with heritage in a more flexible way, more in tune with how people live. If you want to keep everything, compromises must be made about interior systems in the way that things are preserved. If everything is heritage, which is what I believe, then heritage also needs to give us a little slack.

MJ: How do you see the future of the profession? What should architects be doing in these times?

CMB: You know it is funny – there is an idea that to call for a moratorium on new construction is to call for an end to architecture. But this is not the case. Architects have the capacity to envision futures. Now, there is an urgency to act upon these futures. Getting from the utopian envisioning towards a more active way of practicing architecture.

To me there is an urgency to act at the level of clients and of policy making – that is, law. For example, at my lab, RIOT at EPFL, we are getting closer to policymakers. And when talking about policy, I don’t necessarily mean planning but also about specs. Who writes the material specs? All of these things that are so important but don’t sound very attractive. In my lab, we work for example, with insulation. We have seen in the UK, for example, with the Grenfell tragedy that the ways in which specs for insulation were written were destructive, even lethal.

It also means opposing projects. I am now working on a counter project for a client who wants to demolish and replace a building – to not demolish. Of course, the question is who needs to change: is it your client’s budget or the city’s regulation that needs to change so that you can accommodate your client’s expectations and not demolish? This requires a significant amount of literacy. This is something that we architects are good at. We know how to deal with the complexity of the construction site, so we must be more courageous at the level of the day-to-day engagement with the client.

MJ: Do you think architects should be more involved in the brief making itself and not just executing a brief?

CMB: Yes, and in challenging the brief. Good architects have been very skilled at challenging briefs for themselves. For their own design desires. To force upon the client the form they wanted to have or the materials they wanted to have.

It seems that, since we can push for our aesthetic and formal agendas, we should be able to push for other agendas. And I don’t think these are necessarily disassociated. I don’t think that architecture that is non-extractive or socially or politically aware needs to be ugly. I believe that there is a possibility to reconcile form and content. It means that you have to rethink your design. You need to accommodate. For example, for people who work with reuse, this is a clear surrendering of some power from the point of view of the architect. You might not be able to have the form you wanted if you have to accommodate existing materials.

This is a design task! I believe that this is something we are good at. To me, as a profession, we are not at all endangered by these questions. On the contrary, it means more work. Repurposing and refurbishing the built environment as we know it. This is a fantastic task ahead, quite the opposite to the end of architecture. ↙

MATTI JÄNKÄLÄ

Architect finding his place in the Anthropocene. Working to change paradigms of construction as part of the You Tell Me Collective. Exploring the dynamics between architecture, social movements, and property markets as part of the architectural practice Vokal.