Architects as Mediators of Change

Over the recent decades, the temporary use of vacant spaces has been recognised as a sustainable and inclusive approach for managing urban change. In her doctoral thesis, Hella Hernberg found out that, for architects, working with temporary uses can be an opportunity to challenge structures that restrict typical architectural work.

In February 2017, I sat in a meeting room in a vacant office building in the Kera suburb in Espoo, the neighbour city of Helsinki. I was accompanied by a representative of a large Finnish property investment company and three high-level municipal officials. I had been commissioned as a consultant to initiate the temporary use of vacant office and warehouse spaces in a district struggling with almost 50 per cent vacancy. The goal of the project was to revitalise the dormant office district, together with local cultural actors, sports clubs and entrepreneurs, while the longer-term urban planning was being prepared.

The intention was to start the temporary use of Kera in this building, for which we had already found potential tenants. However, the property owner announced a withdrawal from the project, as they had faced problems in air conditioning. Arguments for sustainable or profitable property management were of little help. In the end, the temporary use project progressed with other property owners in the area. Now, five and a half years later, the same office building still stands vacant.

As an architect in a temporary use project, I was caught up in a tangle of divergent interests. There were conflicts between the established operational models of the property owners, the City of Espoo strategic goals and bureaucratic practices, as well as the needs and wishes of those searching for premises.

As a result of societal changes, various kinds of spaces and buildings are continuously left vacant. One example is that the Helsinki metropolitan area currently has 1.2 million square metres of vacant office spaces.1 Different types of vacant spaces, such as schools, retail or industrial premises, often remain pending decisions on their future use for months, years or even decades.

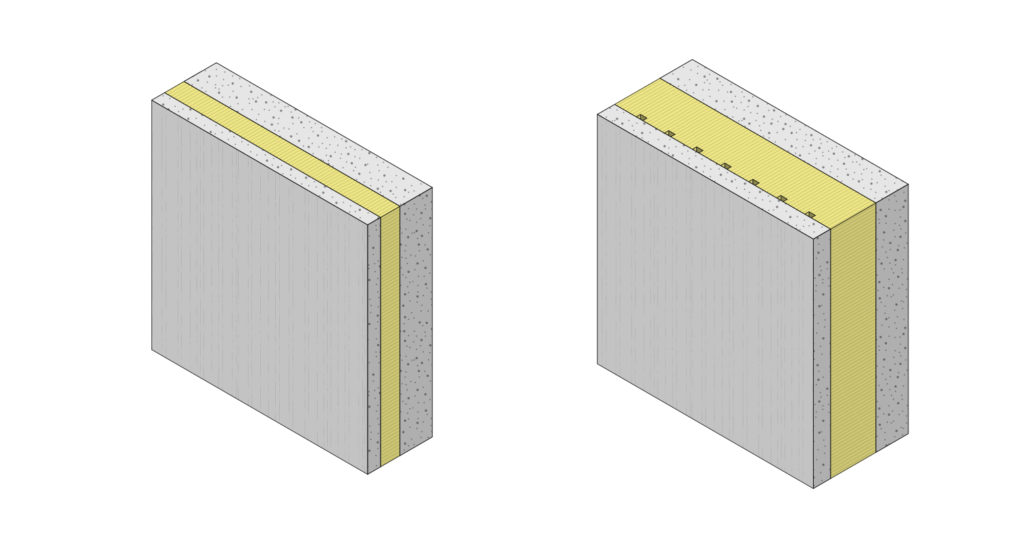

At the same time, there is an urgent need to radically reduce the emissions and the use of material resources within the built environment.2 Vacant spaces are a waste of resources and a lost opportunity for the potential users. Therefore, an important question is how to enable more flexible and adaptable use of existing spaces and buildings over long lifecycles. Could a more flexible reuse of existing spaces and buildings be a way to reduce the need for new construction?

Changing Architectural Work in Times of Environmental Crisis

The flexible and adaptable reuse of the existing building stock requires a systemic change across the industry, concerning also architectural work. My doctoral thesis, examined at the Department of Design at Aalto University in June 2022, discussed the changing work of architects as part of the temporary use of vacant spaces. I investigated the roles of architects as “mediators”, who seek to advance the flexible use of vacant spaces by, for instance, steering the collaboration between stakeholders, and by negotiating administrative and legislative matters. By “mediator”, I refer to an actor or organisation that manages such processes between stakeholders and societal structures that concern the use of spaces. Mediation work of this kind differs from the work of a real-estate agent but also from the traditional job description and training of an architect. In practice, however, architects are often involved in temporary use. One example is my 14-year experience in projects concerning the use of vacant spaces, urban redevelopment and participation as entrepreneur, civil servant, architect and researcher.

Architecture and architectural work face a pressure for change in the face of the urgent environmental crisis. Scholars have criticised mainstream architectural work of too narrowly foregrounding aesthetic and functional questions and distancing its focus from social matters.3 Furthermore, architects’ dependence on the property sector and speculative development has reduced their impact on what gets built.4 A new kind of active agency is required in order to solve complex global challenges.

Even though the mainstream of architecture changes slowly, there are signs of change. Instead of designing (new) buildings, architects may turn their attention to processes concerning the built environment, such as steering complex collaboration and participation processes. Such a shift of attention away from physical products towards processes is also visible in other fields of design. In architecture, the financial crisis of 2008 and the crash of property markets in many countries made architects reconsider whom they serve and what kinds of problems they were seeking to solve. This change is aptly captured by the concept of spatial agency5 coined by scholars and architects Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider and Jeremy Till. As spatial agents, architects strive to enable the empowerment of others in spatial production. Spatial agents are proactive and define their project briefs themselves. This way, they seek to challenge and change the structures underlying the construction and real-estate industries. A corresponding change is also described by Harriet Harriss, Rory Hyde and Roberta Marcaccio in their book Architects after Architecture (2021)6. They use the term “mediator” for describing central features of architectural work today, such as bridging between diverse actors and seeking to understand and redefine complex problems.

Instead of designing (new) buildings, architects may turn their attention to processes concerning the built environment.

Temporary Use is a Means to Renew Urban Areas and Planning Processes

The term temporary use refers to the activation of vacant or underused premises that are pending decisions on their future use. One of the examples in my doctoral thesis is the Île de Nantes port area, in which temporary use began in 2003 when actors of the creative industries settled in a port warehouse. Over two decades, temporary use has had a significant impact on the renewal of the entire area and the creation of its new image.

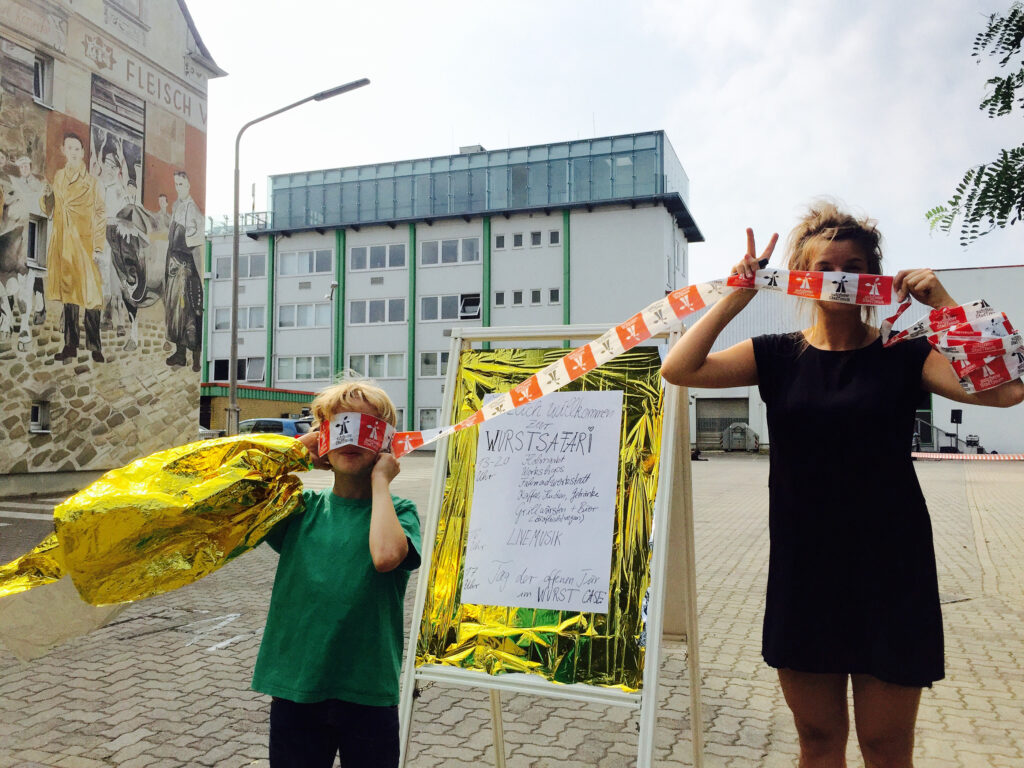

A well-known temporary use project in Helsinki is the Kalasatama temporary project, in which I was engaged as a coordinator at Part Architects.7 The opening of the vacant Kalasatama port for the public use of citizens sparked the birth of new urban culture and new thinking about the use of public spaces. Temporary use is not just a short-term solution for a more efficient use of spaces. Instead, it is also recognised as a means to develop and experiment future longer-term solutions for vacant spaces and changing areas.8 Temporary use also offers diverse local resident groups an opportunity to contribute to developing distinctive urban environments. Furthermore, many scholars have suggested temporary use as part of a broader transformation towards more iterative and flexible planning processes.9 This way, cities could better respond to the changing needs and conditions.

However, temporary uses face many barriers in practice. In Finnish municipalities, these include contradictory interests between various actors, rigid zoning processes, ambiguous legislation, as well as the conventional operational and financial models in property management and development.

For instance, the initial setup of the Kera project in Espoo was challenging. There were many artists in the area who had been struggling to find affordable workspaces for a long time. However, many of the property owners did not consider artists as preferrable tenants. Despite the worsening spiral of vacancy, the owners were sceptical about temporary use; their primary interest was the longer-term repurposing of the properties after five or ten years. The municipal project commissioner aimed to promote bottom-up urban development and circular economy. Yet, at the same time, bureaucratic problems emerged, such as high permission fees for the repurposing of warehouse spaces, which were collected from the tenants. Consequently, as a mediator, I focussed on negotiating with the property owners, advancing the collaboration and synergies between the user groups, and aligning the interests and needs of various groups, in order to enable temporary use.

The flexible and adaptable reuse of the existing building stock requires a systemic change across the industry.

Mediation Work Is Social, Political and Spatial

In my doctoral thesis, I studied both my own work as a mediator and the work of other mediators. As part of the research, I interviewed five European actors. The interviewees include mediators from Samoa, a property development company based in Nantes, ZwischenZeitZentrale, a temporary use agency whose work is commissioned by the City of Bremen, and Free Riga, an NGO that provides a co-development and guardian service for the owners of vacant in Riga, as well as two “neighbourhood managers” from the City of Ghent.

All interviewees considered it important to open vacant spaces for diverse user groups, with inexpensive rents. This way, it is possible to create various alternatives for commercial property development. At the same time, the mediators advanced a dialogue between citizens, property owners and local administration. In a broader sense, mediation work aims to turn the entrenched processes of urban and real-estate development more flexible and inclusive.

A key finding in my doctoral thesis was the social and political nature of mediation work, even though the work deals with spaces. Mediation work does benefit from the spatial competencies of an architect; the understanding of architectural drawings, zoning plans and processes, as well as regulatory issues is useful. Yet, the work also concerns social and political issues such as the ownership of spaces, power relations, prevailing practices and norms, the dynamics between actors, and real-estate business.

Mediation work contains an opportunity to reconfigure architectural work and, to a degree, break away from the structures that steer it.

Three Mediator Roles

In my doctoral thesis, I identified three key mediator roles that are based on my empirical studies, as well as on literature in the fields of architecture, participatory design and urban sustainability transitions. The nature of the first role is social: mediators broker the collaboration and partnerships between actors. It is essential for mediators to build trust and mutual understanding between the users of spaces, the property owners and local government officials. These actors often simply speak a different language. In Riga, the mediator developed a novel co-development model between the users and the property owner. In the model, temporary use was a means of experimental property development, and the resulting increase in value would be shared between the users (i.e. the content developers) and the owner.

The second mediator role is more political: mediators negotiate the structural conditions in temporary use, such as legislative and administrative questions or other matters relating to prevailing practices. The activities of a mediator include lobbying for temporary uses, negotiating interpretations of and exemptions from regulations, identifying incentives, as well as tailoring the operational models and rental contract terms for temporary use. For instance, the City of Ghent neighbourhood managers had a mandate to negotiate temporary exemptions from regulations, as the city strategy aimed to promote experiments. In turn, the mediator based in Nantes had become an expert in developing creative solutions within the strict framework of French legislation. This enabled, for instance, the use of former port warehouses as office space for creative industries.

The third mediator role that I identified focusses on building capabilities for temporary use. As temporary use differs from many established conventions in urban planning and development, there is a need to develop related competence and understanding. The different actor groups can also learn from each other. For instance, experimental user communities have knowhow that can be useful for property owners. The task of mediators is to advance collaborative learning between the different actors with the help of experimentation, participation and by bringing different actors together. According to the mediator based in Nantes, the new insights gained through experiments were the most significant outcome of temporary uses.

How Does Mediation Change Architectural Work?

The mediator roles described above are different from our typical understanding of architectural work, but they also have shared features. In many architectural tasks, architects must negotiate various interests, engage users, or deal with interpretating legislation, even though these matters are not, necessarily, emphasised in their education. In turn, the mediator role focussing on capacity building and experimentation may seem less familiar for architects.

By positioning mediation as architectural work, I do not claim mediation as the exclusive domain of architects only. On the contrary; mediation work benefits from multidisciplinary collaboration and training. Nevertheless, it is useful to study mediation work from an architectural perspective, as it also relates to the broader needs for change that are topical in the field.

How does acting as a mediator change architectural work? Evidently, the focus is shifted from spatial to social and political perspectives. Perhaps the most striking change, however, is about professional ethos. Mediation work does not correspond to a picture of a starchitect, which is, in any case, an outdated image. Mediation work does not highlight the architect’s visual or physical handprint, nor their individual authorship. Mediation work is not as clearly visible – it takes time for change processes to develop. Mediation work is based on multidisciplinary collaboration that requires a humble attitude, as well as an ability to listen to and understand diverging views concerning the use of spaces. These features – collaboration, a humble attitude, as well as a focus on societal structures, processes, and other issues beyond buildings – also correspond to more general changes in architectural work.

I argue that mediation work contains an opportunity to reconfigure architectural work and, to a degree, break away from the structures that steer it. For instance, architects are dependent on clients in real-estate business, but to address the environmental crisis architects must take a stronger role. As the eventual goal in mediation work is to advance change processes, mediators must negotiate and challenge prevailing practices and norms. Mediators, too, are naturally dependent on paying clients. However, as their work is of emerging and constantly developing kind, mediators have agency in shaping the contents of their project briefs. A search for new professional approaches requires a proactive attitude and it may include risks. At the same time, however, it empowers us to choose what kinds of problems we want to solve in our work. In my view, this is one key to a sustainable change in the field. ↙

HELLA HERNBERG

An architect and scholar specialising in sustainable and resource efficient urban development and the mediation of multi-stakeholder collaboration. Before her doctoral research, she ran her own company, Urban Dream Management, and worked at the Ministry of the Environment and different architecture firms. The thesis Architects as ‘Mediators’ – Socio-political roles in mediating the ‘temporary use’ of vacant spaces (Aalto 2022) is available online.

1 Catella: Markkinakatsaus, Suomi. Kevät 2021.

2 On the global scale, the construction sector produces approximately 35% of greenhouse gas emissions and 30% of waste. Buildings embed approximately 50% of the world’s natural resources. The embodied emissions from building materials and construction have a significant share out of the life cycle emissions. Ympäristöministeriö: Rakentamisen kiertotalous. Verkkosivu 2021; Martin Röck, Marcella Ruschi Mendes Saade, Maria Balouktsi ym.: ”Embodied GHG emissions of buildings – The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation”, Applied Energy 258 2020, 1–12.

3 Kenny Cuper: ”Where is the social project?”. Teoksessa Swati Chattopadhyay & Jeremy White (toim.): The Routledge Companion to Critical Approaches to Contemporary Architecture. Routledge 2020.

4 Jeremy Till: ”Architecture After Architecture”. Teoksessa Harriet Harriss, Rory Hyde & Roberta Marcaccio (toim.): Architects After Architecture: Alternative Pathways for Practice. Routledge 2021; Peggy Deamer: The Architect as Worker: Immaterial Labor, the Creative Class, and the Politics of Design. Bloomsbury 2015.

5 Nishat Awan, Tatjana Schneider & Jeremy Till: Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture. Routledge 2011.

6 Harriet Harriss, Rory Hyde & Roberta Marcaccio (toim.): Architects After Architecture: Alternative Pathways for Practice. Routledge 2021.

7 Part Architects acted as the coordinator of the Kalasatama Temporary project in Helsinki from 2009 to 2011. I contributed in the project as a Part employee, together with partners Johanna Hyrkäs and Tuomas Siitonen.

8 Panu Lehtovuori & Sampo Ruoppila: ”Temporary Uses as Means of Experimental Urban Planning”, Serbian Architecture Journal, 4(1) 2012, 29–54; Lauren Andres & Peter Kraftl: ”New directions in the theorisation of temporary urbanisms: Adaptability, activation and trajectory”, Progress in Human Geography 2021, 1–17.

9 Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer & Philipp Misselwitz: Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use. DOM Publishers 2013.