Editorial: Finland Is Demolishing, but for How Long?

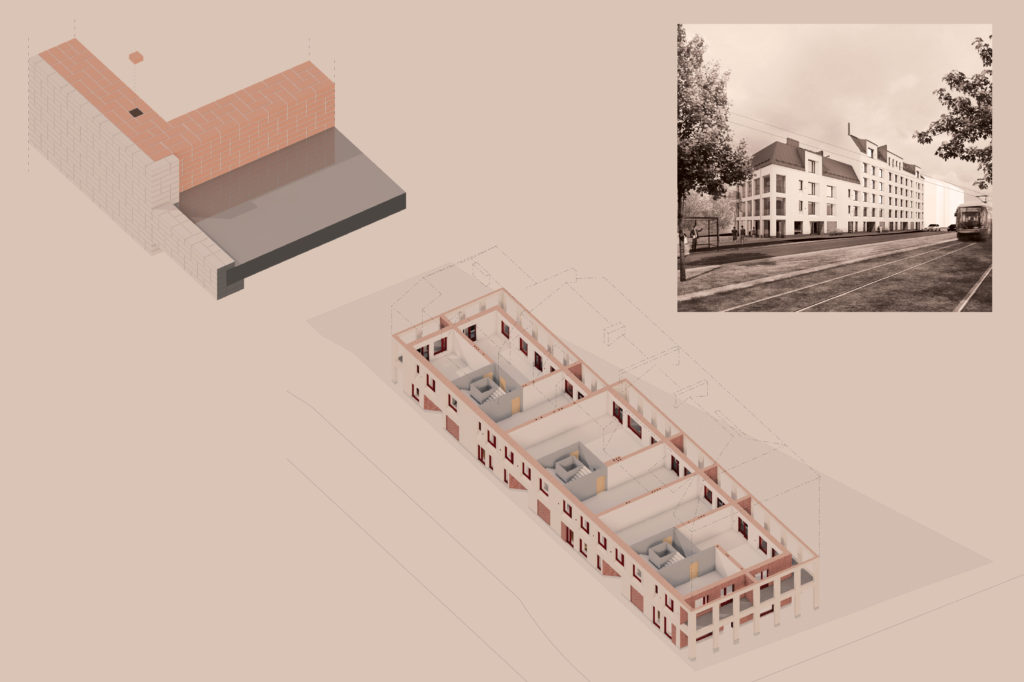

monumental building in the city. Nevertheless, it was demolished just 34 years later. Image: Finnish Heritage Agency / Cultural Heritage Drawing Collection / Åkerfelt Collection

Newbuild and refurbishment always require the destruction of existing things – no matter whether it deals with the soil and vegetation in a plot, buildings on the plot, later additions, or damaged and worn building elements. However, along with short-sighted techno-economic thinking, we have drifted to a situation in which useful buildings are torn down, as the solutions in the buildings, which used to be modern at their time, no longer fulfil the demands of the present. This results in a constantly growing mountain of construction and demolition waste – which amounts, in Finland alone, to more than 13 million tonnes a year – the efficient utilisation of which would require the development of a new industrial infrastructure.

Hence today, demolition sites are an indivisible part of our landscapes, as office buildings, schools, hospitals, shopping centres, industrial buildings and detached houses are disappearing one after another, at an annual rate of approximately 4,000 buildings. Recently, attention has been drawn to problematic properties in declining districts in which financing for the maintenance and renovation of these properties cannot be found. However, the risk is much larger for the modern building stock in the growing cities.

Currently, the average age of buildings that are demolished is around 50 years, and therefore, the threat is, above all, directed at everyday buildings that were constructed after the Second World War – that is to say, at the infrastructure of the Finnish welfare state. Many buildings constructed as late as in the 1990s have also become demolition waste. As the architecture of this period has not yet been comprehensively studied and no broad inventory of it has been made yet, buildings may be torn down before their values have been identified. The losses suffered in recent years include sites that were earlier presented by the Finnish Architectural Review: the Rettig tobacco factory in Turku (Kurt Simberg 1960), Chydenius school in Kokkola (Osmo Sipari 1965), Kainuu central hospital in Kajaani (Reino Koivula 1969), Pieksämäki town hall (Arto Sipinen & Mane Hetzer 1973) and Metsola primary school in Helsinki (Bitumi Manner 1991).

Less than 6% of the building stock in Finland are buildings that are older than one hundred years. Even so, not even useful and healthy buildings that are of a high cultural heritage value seem to be completely safe. For instance, there are currently plans to replace a printing shop that was completed in the courtyard of the Government Palace in 1900 with a new, larger building. This would irreparably change the unique courtyard created by Carl Ludvig Engel in the early 1800s.

The State should, in every way, promote the preservation and reuse of existing buildings.

Besides the cultural heritage values, demolitions also waste tangible resources. A study published by the Ministry of the Environment last year, Purkaa vai korjata? [Demolish or repair?], pointed out that the demolition of a building and redevelopment cause such a high carbon spike that it takes decades before the new building has compensated for it by means of its higher energy efficiency. In some locations, a demolition may be justified by a densification of the urban structure and the resulting decrease in the construction of infrastructure and traffic emissions, but even then, careful calculations should be made regarding the impacts of all alternatives. So far, there is no credible research available into the combined effect of demolition and densification.

The goal of the Finnish Government is to make Finland carbon neutral by 2035. Consequently, the State should, in every way, promote the preservation and reuse of existing buildings. The new Building Act, which is currently being handled by the Finnish Parliament, seems to steer, however, the development in the wrong direction by allowing deviations in the granting of a demolition permit by using the reuse and recycling of demolition waste as excuses.

Hence, would it be possible to imagine a future in which buildings would only be demolished if absolutely necessary? In order to achieve this objective, fundamental reforms should, at least, be made in the legislation, operating methods and education regarding the construction field. Undoubtedly, an efficient steering method would be to direct taxation into the carbon footprint, the consumption of virgin natural resources or the amount of demolition waste. And could building conservation focus, alongside the cultural heritage values, on natural resources embedded in buildings?

The articles in this issue reflect on the questions of building conservation, demolition, repair and reuse from various perspectives. The project presentations deal with the diverse field of renovation, including restoration, refurbishment, extensions, extra buildings, conversions, transformations and their combinations. ↙