Inspired by Nature

Hiking structures in the Tampere region and the Urho Kekkonen National Park show how hiking shelters with long traditions can be updated to the 2020s.

The coronavirus pandemic has led to an explosion in the popularity of short-distance and nature tourism. Within just a few years, the Kintulammi nature reserve in Tampere has become a popular local tourist destination. In 2017, when the hiking infrastructure was being updated, the annual number of visitors was estimated at around 10,000, but the hiking trails now attract more than 50,000 visitors a year. In addition to nature, what also draws hikers to Kintulammi are the architectural shelters and rest areas designed by Malin Moisio and Manu Humppi. In addition to the shelters in Kintulammi, the following pages present the Viitastenperä Shelter in the Hervantajärvi recreational area in Tampere, as well as the wilderness cabins in the Urho Kekkonen National Park in Lapland.

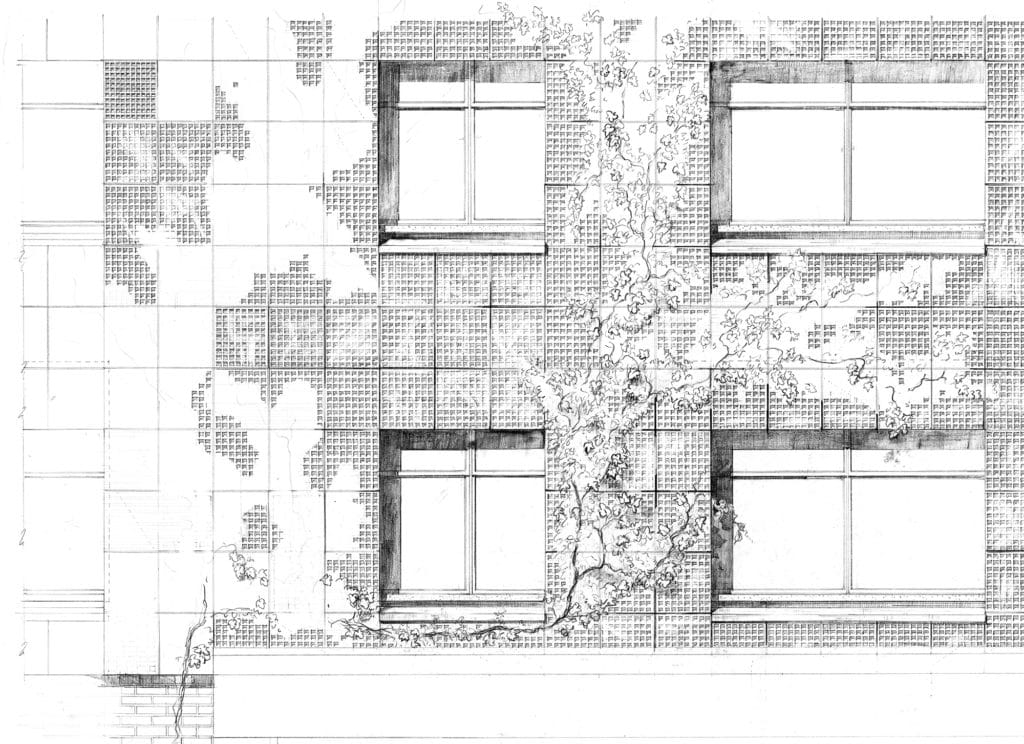

Kirkkokivi Shelter

Tilasto Architects / Malin Moisio

Location Kintulammi nature reserve, Tampere

Gross Area 23 m2

Completion 2018

More photos and drawings of Kirkkokivi Shelter →

Architects MALIN MOISIO and MANU HUMPPI, you have designed several hiking structures in the Tampere region. How did you end up designing them?

Malin Moisio: I’ve been hiking myself since the 1980s, even before I started studying architecture. While walking in the woods, I have always been bothered about how the shelters typically are stuffy and gloomy, and the potential of even the finest locations has not been realised. This is just something I’ve quietly accepted.

My spouse works for the company Ekokumppanit, which is owned by the City of Tampere. He was commissioned to develop the Kintulammi area. Of course, I immediately started pushing him hard at home on an agenda – let’s show them that something different can be done! Ekokumppanit too felt that they now wanted to create a new kind of architecture at an international level.

We gathered together a group of hiking architects for a design workshop, half in the typical voluntary work spirit. One of them was Manu. We know each other from our students days, as well as from hiking and orienteering circles.

Manu Humppi: I too have been hiking all my life, and the issue is close to my heart. My Master’s thesis in 2007 dealt with peat goahtis and wilderness huts as well as the Sámi building heritage. Professor Terttu Pakarinen encouraged me to write a book on the subject, which was eventually published in 2014. As a result, I began volunteering to design wilderness huts in Lapland. At the same time, I ended up participating in the Tampere project.

The Rautulampi wilderness hut complex, located in the Urho Kekkonen National Park, made the national news on its completion. It caused some tension among the general public because the wilderness shelters do not look like the norm. They were not log buildings with pitched roofs.

Kaukaloistenkallio Shelter

Manu Humppi Architects / Manu Humppi

Location Kintulammi nature reserve, Tampere

Gross Area 8 m2

Completion 2018

More photos and drawings of Kaukaloistenkallio Shelter →

The shelters and huts you have designed are indeed different from the Finnish tradition of building amidst nature. How did you come up with such forms?

Moisio: For me, the spirit of the place is central. In the Kirkkokivi Shelter, for example, a boulder-shaped church stone is the real attraction, and it provided the inspiration. I also want to draw from tradition: when, for example, a campfire is built on the ground, the shelter looks like a traditional dwelling, but the shape can still be modern.

Humppi: The design is based on recognising and cherishing the values of the Finnish hiking tradition. It is often the purpose and functionality that guide the design. In Rautulampi, for example, the starting point is an almost over-the-top functionalist idea: one end of the building is lower because less space is needed there. This way, not so much firewood is required for heating, as it’s an expense to transport it to the site.

Manu Humppi Architects / Manu Humppi

Location Urho Kekkonen National Park, Sodankylä

Gross Area 91 m2

Completion 2021

More photos and drawings of Rautulampi Huts →

What other limitations are involved in the design of structures in remote locations?

Humppi: Zero-maintenance is important. For instance, to avoid someone having to regularly renew paintwork, the materials received no finishing treatments. Structures need to be able to cope with both hot and cold. Serious consideration must be given to the site conditions. One night the roof of the previous Rautulampi hut, which later on burned down, blew away due to the strong winds in the open fell.

Moisio: At Kintulammi, the aim was for it to be accessible only along footpaths. I myself am all for this idea. Barbecue shelters can be built even in urban areas, but a wilderness shelter should somehow differ from them. Since there are no roads, all the building materials have been towed to the site by snowmobile and all-terrain vehicle, and to the Viitastenperä Shelter by boat. The shelters of Kirkkokivi and Viitastenperä are made entirely of the same type of timber, which was hauled in abundance to the site. Since there is no electricity on the site, practically all the work was done with a chainsaw. This places limits on how fine a finish can be achieved. The construction of shelters involves more of a rugged kind of forest construction.

Viitastenperä Shelter

Tilasto Architects / Malin Moisio

Location Hervantajärvi recreational area, Tampere

Gross Area 9 m2

Completion 2021

More photos and drawings of Viitastenperä Shelter →

As hikers, you yourselves also use hiking shelters. What is the perfect shelter?

Moisio: Hiking shelters should be easy to use. It’s a question about the basics. You carry stuff along on the trip, and at the shelter you shouldn’t have to think about where to put it. The campfire provides warmth and is placed not too far from the occupants. The fire and the edge of the shelter are of a suitable sitting height. You shouldn’t need a headlamp when using the dry latrine in the middle of the day. These are simple things, but if the professionals haven’t thought about them, they won’t miraculously turn out successful. When I visit the forest, however, the most important thing is nature. All too often, for instance, the lakeshore shelter is placed in a thicket so that you cannot see the lake.

Humppi: The perfect shelter is a result of subtle observations that can make life easier. Where can you hang a shirt to dry, for instance? All sorts of small things you won’t necessarily think about when sitting by your worktable in the warmth of a studio. It’s not the architecture itself, however, that is being designed here, but rather sites where you can enjoy being amidst nature. The structures are just backdrops for other activities.

Moisio: Although the location is the most important aspect, the architecture adds value to it. I am immensely delighted when I go to a new place and see that some thought has gone into the architecture. Even in Kintulammi, people go expressly to see the shelters. As people go out into nature, they learn to appreciate and protect it. The more that people move around in nature, the more beneficial it will be.

For which location are you designing your next shelters?

Moisio: At the moment we are designing together a range of different rest areas for Metsähallitus. Instead of fitting it into a specific place, I now have to imagine a shelter that is replicable. We have divided the designs into archipelago and wilderness ranges, as these are such vastly different habitats.

The design of hiking structures is breaking new ground in Finland. One often hears “Was it really necessary to have an architect for this too?” But just as you can see the planned environment in city parks, so too does nature deserve professional design. ↙

Edited by: Essi Oikarinen, Kristo Vesikansa