Would Joint Building Ventures Save the Quality of Housing Production?

Contrary to what is often thought, joint building ventures have a long history in Finland. If things had turned out differently in the 1960s, joint building ventures could still be mainstream.

In Finland, joint building ventures have been brought into the discussion during this millennium, but, so far, they have remained a marginal phenomenon. Models are searched for especially in Central Europe, where joint building ventures are common. However, the phenomenon is not new in Finland, either: most of the blocks of flats that were built in Helsinki before the 1960s were developed jointly by a group of people. At the time, similar construction companies as today – that bought a plot, founded a housing company, developed a building and sold the homes – constituted a minority in the housing production.

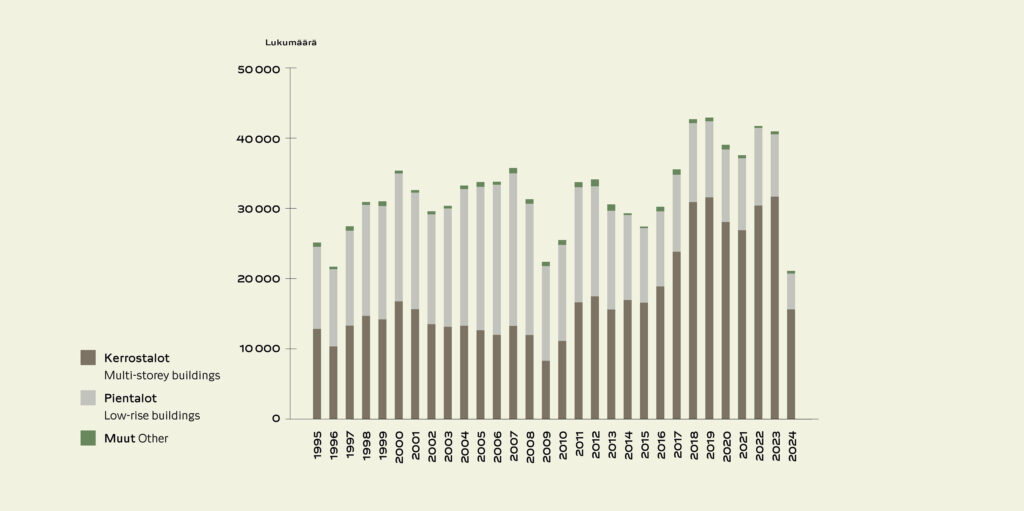

Joint building ventures enabled an exceptionally large housing production in Helsinki during the period between the First and Second World Wars. For instance, in 1928, more homes were completed in Helsinki than in 2018. However, politicians made joint building ventures almost impossible in the 1960s, because they ate up the profit margins of the investors and construction companies.

Housing Companies as Developers

The foundation of joint building ventures was laid by the Limited Liability Companies Act from 1895, which clarified the joint ownership, design, development and administration of properties. The situation further improved due to the Limited Liability Housing Companies Act, which was laid down in 1926. It was exceptional, even on an international scale. As a poor country, Finland could not afford to build large non-profit residential areas, which were, at the time, constructed especially in Germany and the Netherlands. Thanks to the Limited Liability Housing Companies Act, shareholders were able to receive a loan against their shares and correspondingly, housing companies were able to receive a construction loan against the property. This way, poor banks were able to borrow capital from abroad. This money was also smoothly transferred to the industry that manufactured paper, pulp and plywood for exports, making Finland wealthy.1

Before the Second World War, many housing companies in Helsinki were founded this way: a group of interested people drew up a shareholders’ agreement and articles of association, and they provided the original own funds, bought a plot, hired an architect and, in a year, moved to a completed building together with others who had purchased their shares later. The founders and developers of the housing companies represented various social classes: blocks of flats were developed by railway workers, teachers, civil servants, capital investors and bankers. Cooperatives also functioned as housing developers all the way to the 1950s. The best-known of them was Elanto, which developed several blocks of flats in Helsinki.2 The groups that developed for their own needs quickly adopted new construction technologies, such as lifts, bathrooms, central heating and modern kitchens, in particular. Aino Aalto and Salme Setälä were important actors in the development of modern kitchens.3

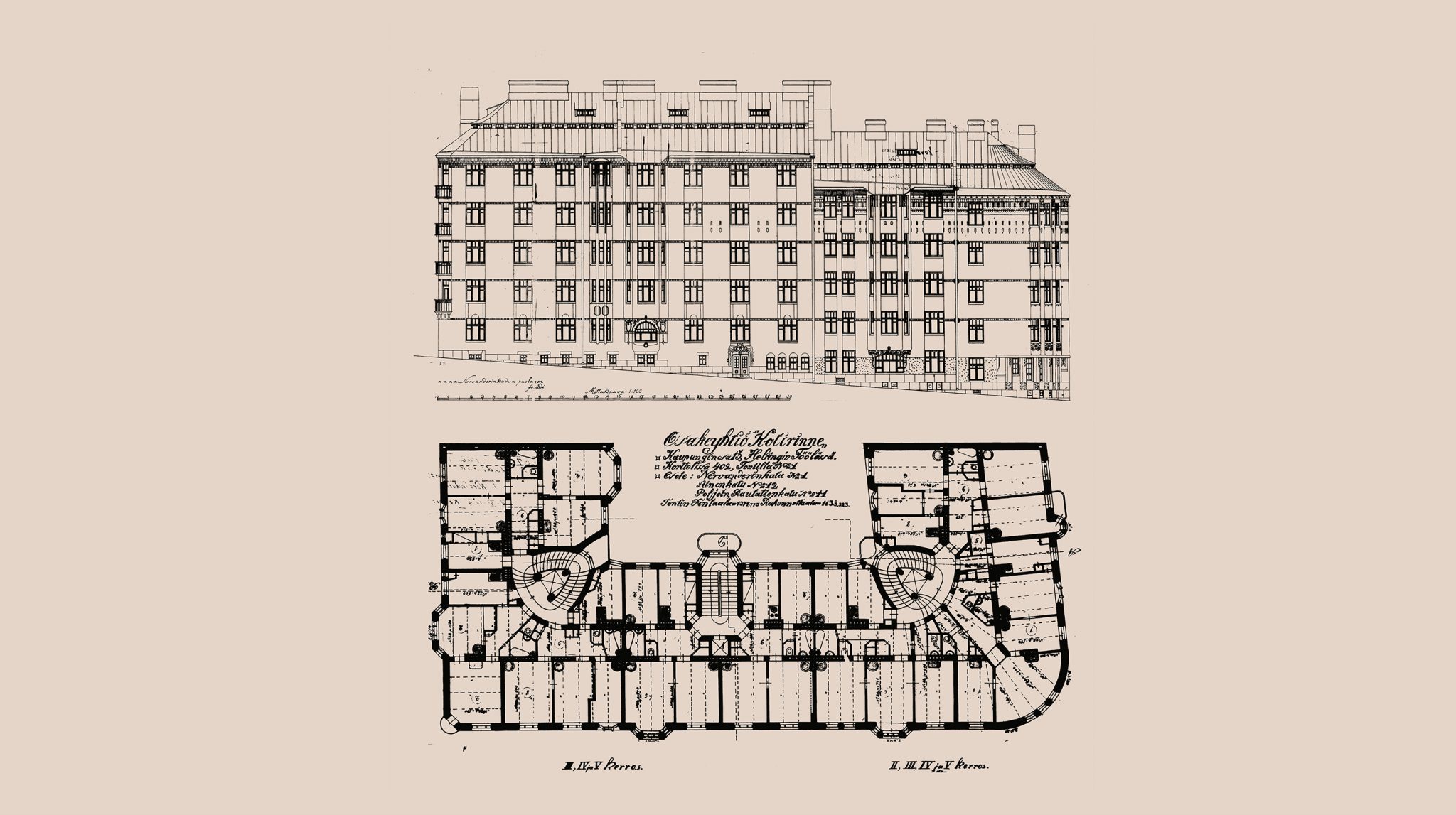

A good example of the early joint building ventures is As. Oy Kotirinne, which was completed in Etu-Töölö, Helsinki, in 1911. It was designed by Usko Nyström, a top architect of the time, for a group of school teachers. Nyström also purchased shares from the company and acted as a developer, invoicing the company. The teachers wanted to have modern architecture and new conveniences in the building: a lift reservation was made for future needs, each flat had a bathroom, and a central kitchen provided food for the busiest residents. Several flats remained in the ownership of the company in order to cover the charges for common expenses, and the company even made the building taller in 1934 in order to improve its finances.4

The execution methods of recent joint building ventures – such as the housing companies Helsingin Malta (ARK-house architects 2013), Sompasaaren Sumppi (Cederqvist & Jäntti Architects 2019) and Kalasataman Messi (Architects Sarlin+Sopanen 2021) – are more simple than the practices of the 20th century. The most significant difference is the role of developer consultants and construction companies as project leaders. Compared with other free housing production in Helsinki, the solutions of the housing companies are of a much higher quality and the purchase price of the dwellings is cheaper. However, the profit margins of the developer consultant and main contractor have also been considerable in these cases. Joint building ventures, driven by consultants and construction companies, are more simple and less risky for housing companies than the prior practices, but they are more expensive.

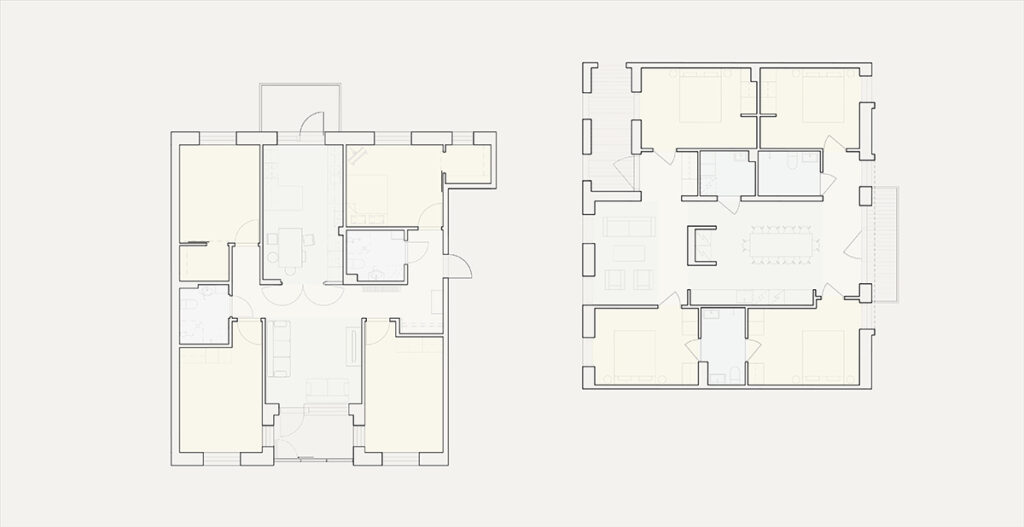

3rd floor (apartments, hobby room and rooftop terrace), As. Oy Kalasataman Messi.

Recently, smaller terraced houses and detached houses have been built independently. They are not dependent on large developer consultants and construction companies. In Helsinki, the problem is that the number of planned terraced houses is small compared with blocks of flats, even though small-scale production would allow new actors to enter the insufficiently competed market.

The largest obstacle to joint building ventures becoming more common is the fact that it is difficult to receive loans from banks, let alone from private financiers. The situation was easier one hundred years ago, when it was possible to receive financing from various sources, ranging from private investors to fire insurance funds. For instance, As. Oy L. Viertotie 36 (V. Toivio 1927) in Töölö, Helsinki, applied for loans – according to the minutes – from almost ten different sources, until the loans were consolidated to Hypoteekkipankki after the completion of the housing company. The equity for development was most often 30–40% and the loan capital 60–70%, which is also the case today in the construction of new housing financed by housing company loans. The acquisition price of dwellings, in proportion to median gross income, was only a fraction of the current acquisition price.5 However, interest rates were high at the time – about 10% during the period between the First and Second World Wars – and the Wall Street Crash 1929 suspended the loan market for years.

Architects, Construction and the Finances of the Housing Companies

In the early 20th century, a housing company that was to be founded and built jointly usually first hired an architect who often also became a shareholder in the housing company. Together with the housing company’s board of directors, the architect was in charge of the design, development and construction work. A clerk of works hired by the housing company received and inspected the construction materials at the worksite, and the clerk of works was in charge of the work of, at the most, a few dozens of builders and paid them in cash, which was borrowed by the housing company.

Occasionally, it has been claimed in literature that the architects who worked during the first part of the 20th century disliked the design of blocks of flats. This incorrect idea is due to the fact that the early construction companies that carried out speculative development did not use architects, because the master builders who owned the companies designed the buildings themselves. However, the developers in joint building ventures used the best architects of their time. For instance, in Jyväskylä, railway workers hired Alvar Aalto to design the Aira building in 1924. In addition, many other architects, such as Lars Sonck, Ole Gripenberg, Sigurd Frosterus, Niilo Kokko and Arvo Aalto, acted as speculative developers before the Second World War.

Compared with the housing production designed by the master builders, the housing companies that were constructed in joint building ventures were clearly of a higher quality, which is why there was lively discussion on the quality of the housing production one hundred years ago. Housing speculation carried out by master builders was criticised on the pages of Arkkitehti in particular, and Hilding Ekelund, Editor-in-Chief, called the architects used by speculators spineless.6

The criticism was especially targeted at Leuto A. Pajunen and his brothers. Pajunen was the most successful and notorious of the speculative developers. He became known for using the same facade in many different blocks of flats, very large plan depths and gloomy central corridors that only had one lift. It is easy to find similarities between the criticism provided one hundred years ago and the discussion that is held today. In the end, discipline was restored amongst the early speculative developers by adopting new building regulations and ordinances.

During the period between the First and Second World Wars, master builders were not eager to build street-level commercial facilities, as the profit margin from commercial facilities for a construction company was much smaller than from housing. The vibrancy of street spaces and street-level services worried many people in the same way as today, even though shopping centres were not yet planned outside city centres. Unlike the early speculative developers, the developers in joint building ventures wanted to safeguard the finances of the housing company that they had founded. This meant the renting out of dwellings owned by the housing company in order to cover the company’s running expenses. In some cases, the housing companies were made so rich that the rental income also covered the amortisation of the building loans. Good examples of this are the housing companies founded by architects Niilo Kokko and Arvo Aalto in Kamppi and Lauttasaari, Helsinki. These housing companies owned two thirds of the flats and all commercial facilities.

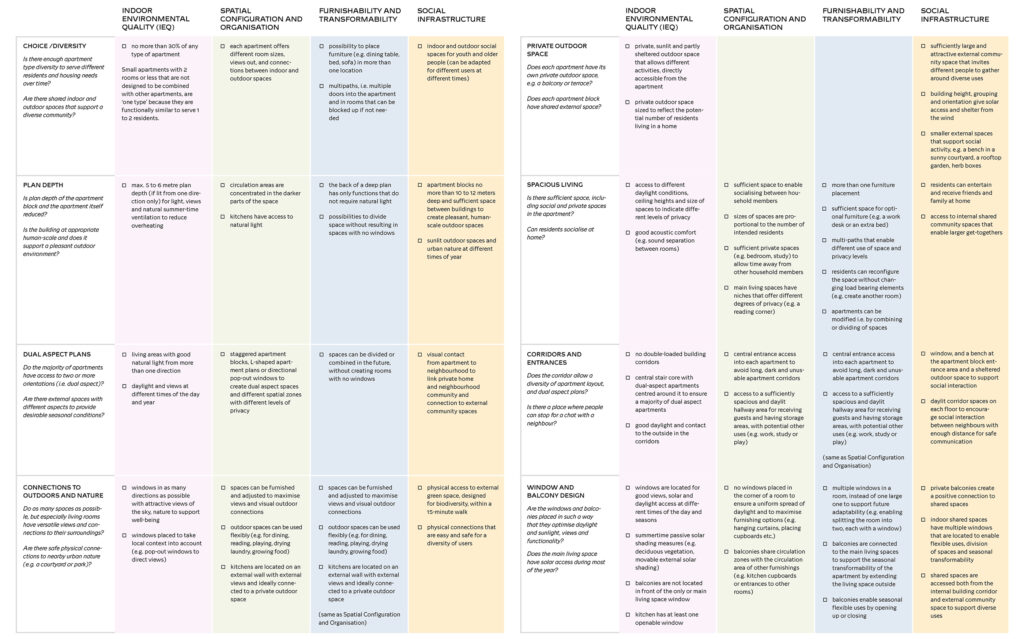

In addition to housing, recent joint building ventures have also come up with group facilities that improve the quality of housing, such as shared kitchens and roof terraces with gardens. In the production of other forms of owner-occupied housing, these are only built when particularly demanded by the City or building regulations. Consequently, organisations that advocate the interests of property investors and developers have demanded, for a long time, that these kinds of regulations are given up and that they return to the same kind of comprehensive construction as was driven by speculative developers in the 1970s, when the developers of large suburbs were almost given free hands in the design and execution on the condition that they also fulfilled the obligations that would otherwise belong to the municipalities, such as streets, technical networks and services. However, the construction companies of today would not be willing to fulfil these obligations. As a result, the objective that is included in the new Land Use and Building Act, which is being prepared, might lead to a lower quality level than what was produced during the most criticised phase of the history of housing production in Finland.7

Joint Building Ventures Came to an End due to Political Decisions

After the Second World War, construction companies took an increasing amount of power in speculative development, but the old practices were still in force during the reconstruction period. Arava, which was the first State support system for housing production, was founded – alongside the rural settlement support – in 1949, and, in some cases, the State guarantee for the loan provided front-line veterans and war widows with an opportunity to acquire the shares for their homes without initial capital. Along with the new financial arrangements, the housing production in Helsinki achieved its peak in the 1960s, when the largest political parties decided that plots planned for blocks of flats are only allocated to those construction companies whose political opinions are similar to those of the largest political parties. One reason for this was the Asuntosäästäjät association, led by Matti Ilveskorpi. The association carried out joint building ventures successfully in Vuosaari, Helsinki. Construction companies and banks that financed them felt that the association posed a major threat to them.

The new cartel situation led to a crash in the volume of housing production in Helsinki in the 1970s and a subsequent long period of low production. In order to solve these grave mistakes made in economic policy, the Hitas system was created in the early 1980s. The purpose of the Hitas system was to attract middle-class residents – who had fled the housing prices that had been increased by the cartel – back to Helsinki. Despite many efforts, it is only now that the volume of the housing production is rising to the level of the peak years of the early 1970s. This also deals with the fact that the labour productivity in the construction sector has remained at the same level for almost half a century – in the past, a brick-framed block of flats in Töölö, Helsinki, was drawn and masoned by hand in a shorter period of time than a data modelled, prefabricated building is completed today.8 Although labour productivity has not increased, the housing prices in the centres of growth have risen to a much higher level than, for instance, in Germany, which is a model country of joint building ventures.

Taxation Favours Housing Investment

The land use policy and taxation have, for a long time, favoured large construction companies and investors, at the expense of residents: at its best, 70% of the acquisition price of an investment dwelling – in addition to other costs – is deductible in taxation. The last rights dealing with the deduction of home loan interest are being removed from owner-occupiers, but, at the same time, the loopholes in the taxation of housing investment and housing benefits increase the prices of the smallest dwellings.9 Consequently, Hannu Rossilahti, Director General of the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (Ara), has aptly called this neoliberal redistribution of housing wealth neo-feudalism in which property assets are only consolidated to the ownership of a few modern feudal lords.10 Hannu Rossilahti and Hannu Penttilä, Deputy Mayor of the City of Vantaa, also consider it to be a shame that housing finance support has been removed from owner-occupied housing.11

In practice, housing companies do not need to pay taxes, as they do not usually make a profit. However, VATT Institute for Economic Research has brought to the discussion a possible taxation of imputed rental income that the owner-occupiers would pay – as capital income tax – from the imputed rental income dealing with their homes.12 This would make the conditions of owner-occupied housing more difficult and benefit rental housing investment that is partly funded by tax revenue. A considerable increase in the taxation of owner-occupied housing – for the benefit of investment activities – would hardly improve the quality of housing production, as an owner-occupier requires higher quality than a housing investor.

The quality of the production of new housing most of which will become investment dwellings has continued to decrease, so it is justifiable to ask whether the quality would improve if there were more joint building ventures carried out by owner-occupiers on the market? One can even claim that the construction companies that operate in the free owner-occupied market are, in many ways, expensive and unnecessary intermediaries for buyers of dwellings, as they order most of the construction work from subcontractors, in the same way as the developers in joint building ventures. The decentralised production of owner-occupied housing built for oneself – which was dominant until the 1960s – was much cheaper and of a higher quality. In Finland, there are also a large number of architects specialised in housing design who would be capable of acting as developer consultants in joint building ventures.

In recent years, Helsinki has taken careful steps towards joint building ventures, but, so far, the political measures have been insufficient. Joint building ventures are no silver bullet that would find solutions for all problems in the housing production, but they would help to improve the poorly functioning market. The largest obstacles to joint building ventures are the availability of financing for the construction period, municipal land-use policy and the unfair taxation of owner-occupied housing for the benefit of housing investors. Fixing one of these obstacles would make it possible to relaunch the form of housing production that has proved to be good. At the same time, it would also provide better alternatives to bulk production, as the architects would directly respond to the owner-occupiers’ needs. ↙

JUHANA HEIKONEN

Architect SAFA, D.Sc. (Tech.), post-doctoral researcher in the ERC funded project Law, Governance and Space. Questioning the Foundations of the Republican Tradition at the University of Helsinki. Specialised in the history of housing production and the impact of classical antiquity on western architecture.

1 Seminal works on the subject: Nurmi, Esko; Puro, Laura & Lujanen, Martti: Kansan osake. Suomalaisen asunto-osakeyhtiön vaiheet. Suomen Kiinteistöliitto ry 2017. Neuvonen, Petri; Mäkiö, Erkki & Malinen, Maarit: Kerrostalot 1880–1940. Rakennustietosäätiö 2002.

2 Leppänen, Laura: Osuusliike Elannon Helsinkiin rakennuttamat asuintalot, Helsingin yliopisto 1997.

3 Heikonen, Juhana: “The Influence of German Siedlungen and Bauhaus on Helsinki’s Prewar Housing Companies”. TAHITI. Fokus Bauhaus 2021.

4 Heinämies, Kati: Tästä alkaa Töölö. Asunto-osakeyhtiö Kotirinne, Asunto-osakeyhtiö Kotirinne 2016.

5 Heikonen, Juhana: ”Töölön yksityiset taloyhtiöiden rakennuttajat ja As. Oy L. Viertotie 36”.

RY Rakennettu ympäristö 1/2020.

6 Arkkitehti 3/1938, s. 34 – 35. In addition: Arkkitehti 9/1937, s. 34–35.

7 RAKLI & Kiinteistöliitto: Selvitys kaavamääräysten kustannusvaikutuksista. 2021. The report explains, in a simplified manner, how much more it costs to produce a residential building that is different from the exposed aggregate concrete cubes that were built in the comprehensive construction projects of the 1970s, but without the narrow plan depths and practical layouts of the time.

8 Lohilahti, Oona: ”Rakennusalalla työn tuottavuus ei ole kasvanut 40 vuodessa – onko allianssista tai leanista apua?” Rakennuslehti 4.9.2017.

9 Rantanen, Henrik: The role of housing company loans in apartment price determination. Empirical evidence from largest cities in Finland. Aalto-yliopisto 2019. There is no proper study on the effects of housing benefits, but it has been assumed that housing benefits capitalise into property prices, in the same way as agricultural subsidies.

10 Housing policy presentation 01/2021 of Hannu Rossilahti, Director General of the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA), at the ARA event on 21 January 2021.

11 Hannu Penttilä, long-time Deputy Mayor of the City of Vantaa, criticises the development of housing prices in his retirement interview in Helsingin Sanomat 18 July 2021.

12 Eerola, Essi; Lyytikäinen, Teemu & Saarimaa, Tuukka: Asumisen verotus. Katsaus taloustieteelliseen kirjallisuuteen. Valtion taloudellinen tutkimuskeskus VATT 2014. Response to this: Heikonen, Juhana: ”Omistusasumisen uudet ja vanhat verot”. Kiinteistölehti Uusimaa 1/2021.