Published in 3/2021 - Sacred Space

Remembering Kristian Gullichsen (1932–2021)

The loss of Kristian Gullichsen (1932–2021) leaves a large void in the architectural world of Finland and in the lives of his family, friends and colleagues at home and abroad. As well as being an outstanding architect in his own right, he was a promoter of artistic culture in its diverse forms, even at times an ambassador representing and promoting modern Finnish architecture past and present on an international front. There were his public roles in institutions such as the Museum of Finnish Architecture, the Alvar Aalto Foundation and the restoration of Aalto’s Library in Viipuri. In these cases, he was on an international stage.

But there was also the more private Kristian, a charismatic personality active behind the scenes, ever insisting upon quality in the selection of architects, projects, even exhibitions. I recall what a pleasant surprise it was when the Alvar Aalto Medal was awarded to the fine Colombian architect Rogelio Salmona in 2003 whose buildings I knew firsthand and appreciated greatly. This was a discerning and unexpected choice in favour of work of long-term value insufficiently known outside Latin America. I later learned that Kristian had had a lot to do with this wise selection which was completely beyond the range of contemporary fashion.

There is no need here to be reminded of Kristian Gullichsen’s architectural trajectory over the years. But the time has surely come for a critical and historical reassessment rescuing his unique production from standard legends and polemics: a major retrospective exhibition and book? He drank deeply from major springs of inspiration such as the work of Le Corbusier and of course that of Aalto which he knew intimately from the experience of living as a child in the Villa Mairea and even working briefly in the Aalto office. Aalto was part of the air which he breathed but like several other architects of his generation Gullichsen needed to create distance from the master and tended to regard modern architectural tradition as a stockhouse of “ideas which have proved good”, concepts and principles that could be reworked and transformed in an evocative language of his own.

Kristian “stole” (to use T.S Eliot’s formulation on invention) what he needed from a range of other architects of course, including Nordic predecessors such as Sigurd Lewerentz. He also drew numerous lessons from vernacular buildings and urban spaces, Nordic, Japanese and Mediterranean. There was no contradiction in his mind between modern architecture and a deep sense of the past, just as had been the case for Aalto. He had a sense of Finnish continuities related to landscape, light and tradition, but his outlook was basically cosmopolitan. I got to know the works that Kristian Gullichsen designed on his own or with his partners Erkki Kairamo and Timo Vormala during several intensive visits to Finland in the 1990s, for instance, when acting as a member of the Finland Builds 8 Jury in 1992. I was gradually able to position his architecture in the complex archipelago of modern architectural culture in Finland.

Kristian Gullichsen’s church designs, Malmi and Kauniainen, made an immediate impression for their subtle siting but also their sophisticated allusions to past modern buildings. Malmi has the character of an elemental meeting house in brick and concrete, almost like a barn. Kauniainen contains echoes of Le Corbusier and Erik Bryggman and uses daylight and shadow to elicit mood. In his other works, Gullichsen worked up and down the scale from the urbane Stockmann Department Store extension to his understated wooden holiday house on an island in the archipelago. His Civic Centre at Pieksämäki (where I first met him in 1991) established an easy relationship with the fabric and landscape of a small town. Gullichsen also obtained major jobs abroad such as the Finnish Embassy in Stockholm which caught just the right note, combining the ceremonial with the informal. Then there was his Lleida University Library in Spain which responded to the warmer climate, the fiercer light and an entirely different sense of place in a Catalan city.

Poetry arising from pragmatic moves, attention to social purpose, a clear rationale, articulate structure and materials: these were among Gullichsen’s strengths. In fact, one of my favourite projects is that for the Pori Art Museum and its extension, an “art hangar” which confirms his attention to the needs of exhibitions, the combination of natural and electric light, and of course the urban context including both the old building and the riverside. When a proper history of Gullichsen’s architecture is written it will need to unravel the complexity of his intentions in responding to the often-contradictory demands of site and client, the richness of his visual culture including painting and sculpture, and his attention to craft and detail. Somewhere behind the forms was a consistent set of values: an ethos to use that word.

Kristian often used another word – empathy – when talking about the need of architecture to touch the mind, the imagination and the senses, to communicate directly by means of space, light, sequence, material and proportion. There was always the pursuit of a few central guiding architectural ideas. He believed in paring away. He detested over-intellectualised architecture and despised empty formalism. As for the sort of vapid theorising which came into vogue in the 1990s in architecture schools, he had no time for it at all: in his office he had a sign next to his desk with the words “Theory Free Zone”.

This phrase was picked up for the title of the book organised by his wife Kirsi Gullichsen and presented to Kristian on his 80th birthday, a compendium containing homages, drawings, texts from over fifty friends all around the world. He felt that buildings should speak for themselves but this did not stop him from speculating. When Kristian got going on a subject which really interested him he came out with fresh and piercing insights that were entirely original. Of course, growing up in Villa Mairea was a tough act to follow and Kristian protected himself from an overbearing mentor with a well-developed sense of irony and a dark sense of humour. He rather enjoyed shocking people with his mischievous riddles.

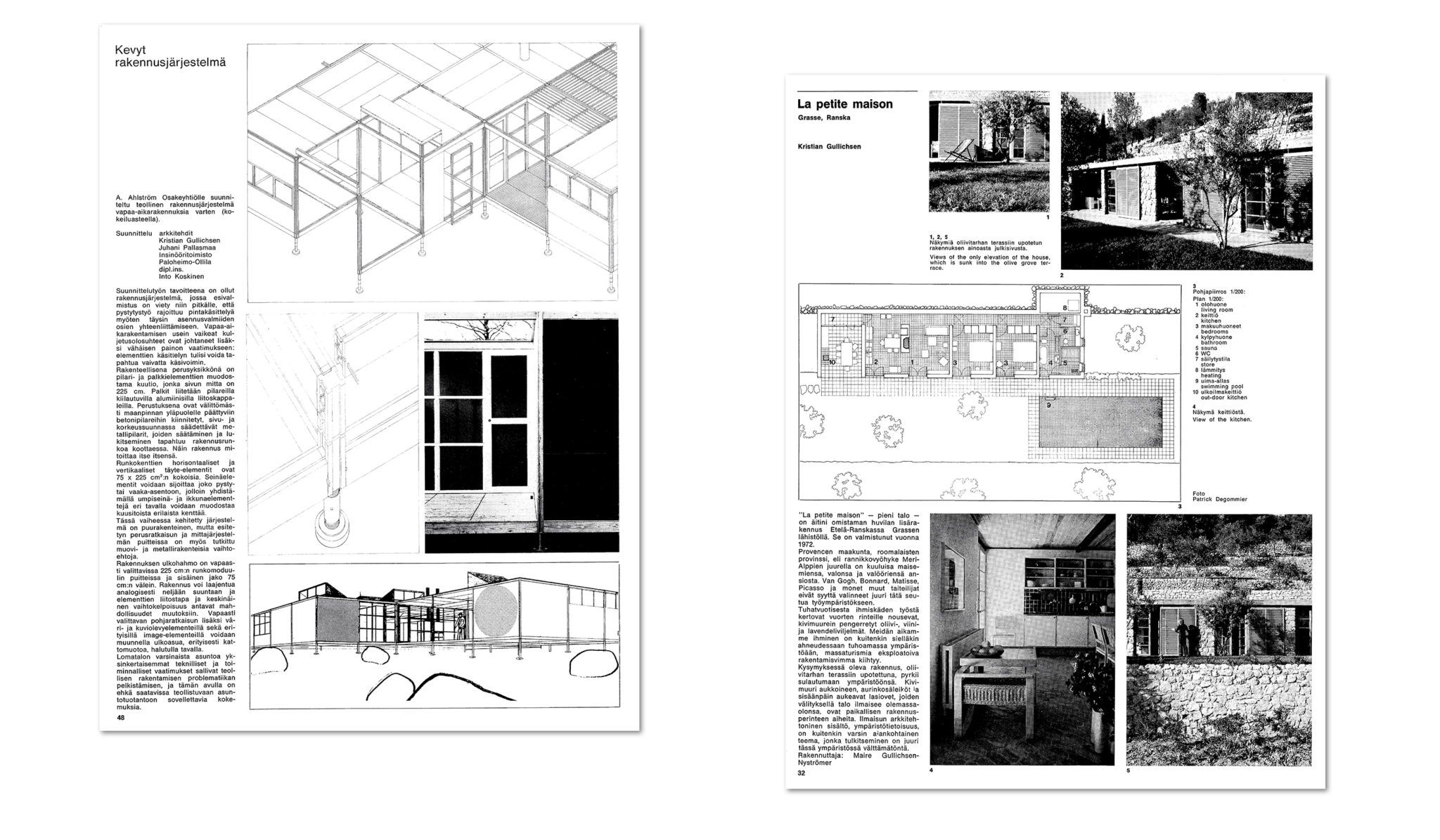

France played an important role in Kristian’s life as it had in the life of his mother Maire through her collection of fine pieces of French modern art. One of Kristian’s best early works is surely the family holiday house inserted into an agricultural terrace just inland from the Côte d’Azur, a minimal building almost invisible from the outside tucked away behind wooden louvres. This dwelling is a sort of Mediterranean cousin of his Moduli 225 timber frame structures developed with his long-time friend Juhani Pallasmaa between 1968 and 1974 in Finland. In fact, a demonstration version of this self-build timber system based on harmonic proportions was presented years later as a full-scale mock up in the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

There were several bridges between Finland and France in those years, some of them encouraged by Aalto’s Maison Carré, others relayed through the journal Le Carré Bleu. Kristian developed a close friendship with the French architect Roland Schweitzer who preached the values of architectural restraint and was an expert in wooden construction including traditional Japanese carpentry. He was deeply touched when awarded the Gold Medal by the French Académie de l’Architecture for the year 2007. In Paris Kristian liked to hang out at the Brasserie Lipp and of course with the background of his mother Maire’s contacts and collection was thoroughly conversant with the great moderns: Matisse, Picasso, Lèger just to mention a few. I remember being a guest in bedroom number one of the Villa Mairea and waking up to discover a Matisse sketch on one wall and a Picasso on another.

Catherine and myself have lived in rural south western France for over thirty years and one of the pleasures for us was to show Kristian and Kirsi, architect and designer in her own right, around our favourite landscapes, dolmens and ruined medieval abbeys and of course to share first rate French home cuisine. Kristian himself was a good cook with a Mediterranean touch in his recipes. He loved visiting and revisiting the works of Le Corbusier. In 1999 as part of the continuing Aalto centennial celebrations a weekend congress was organised in the Centre Tomas More in Le Corbusier’s Monastery of La Tourette by the Director, the Dominican monk Antoine Lion, another of my close friends to have passed on to the next world.

Kristian was President of the Aalto Centennial and had spoken in English all around the world including in Chihuahua, Mexico. He understood French but did not speak it well enough to give an entire lecture so he put it to the vote: “Would it be alright if I gave this talk in English?” A resounding “non” came back from the audience so I stepped in to do the translation. But Kristian opened the proceedings by saying “All the problems of the world would be far less if everybody would speak… [pause]… Finnish!!” Later we sat together in silence in the choir stalls of the church of La Tourette, taking in the light, shade, atmosphere and gravitas of that moving and timeless space. Architecture, we agreed, communicates by its own means.

Kristian was a great storyteller and possessed a highly developed sense of theatre. The Alvar Aalto Symposia brought speakers and guests to Finland from many parts of the world every three years to discuss the state of architecture. After receptions in Aalto’s house and studio in the leafy suburbs of Helsinki, guests were transported by boat northwards to Jyväskylä where the conference took place, but with a stopover at Muuratsalo to visit Aalto’s so called Experimental House with its memorable brick lined courtyard open on one side framing the landscape as if through a proscenium. There Kristian was like a Greek oracle disguised in casual summer clothes, recounting ancient Aaltoesque legends, stirring up reminiscences, always on a fine line between fact and fiction, the serious and the absurd.

But I remember Kristian best of all in the most familiar of his theatrical spaces, his spiritual home, the Villa Mairea at Noormarkku. Here his stock of personal memories took over and invaded the atmosphere of the place and we were transported somehow to the late 1930s when the Villa had just been completed. The past came alive re-enacted in series of tales and humorous stunts. What luck to have been invited there to spend wonderful times together with friends at different seasons of the year moving around from one space to another, inside and outside, with the forest as backdrop. When Kirsi approached me in 2012 requesting a contribution to the 80th birthday volume for Kristian, Theory Free Zone, I decided immediately that I should weave a historical, biographical, and even autobiographical story around my various visits and texts to the house over the years. So, I chose the title “Marking Time at the Villa Mairea” (short excerpts below). With the disappearance of Kristian Gullichsen, we have lost not just a rare individual, but also an era in architecture.

Excerpts from the text “Marking Time at the Villa Mairea”, originally published in Theory Free Zone: Kristian Gullichsen 80 vuotta = 80 år = 80 years, Helsinki 2012 (ed. Ilona Anhava).

William J.R. Curtis

August 1991. “Ça vous plaît?” said the tall man with the pronounced cheekbones who I realized must be Kristian Gullichsen. “Do you like it?” He was referring to the building in which we were standing, glasses in hand, the Civic Centre in Pieksämäki which he had designed in the early 1980s and which had been completed a couple of years before. It was late at night, music was playing and an exquisite Danish lady with golden blonde hair, black and white stockings and a black cocktail dress was spinning around the dance floor capturing a fair amount of attention. She stood out beautifully against the white surfaces and curves which reminded me of both Aalto and Le Corbusier. It was the Saturday night party of the Alvar Aalto Symposium and I had been invited as one of the official speakers. It was my first trip to Finland although I had often been there in imagination. We all took the train together from Jyväskylä to Pieksämäki and on the way over I sat next to Elissa Aalto and we talked about travelling around the Mediterranean. For the return journey in the early hours of the morning I found myself in the Gullichsen group. I was aware of being scrutinised silently by Kristian who seemed to decide I was alright. He had a flask in his pocket and poured out something pretty strong in small receptacles, handing one to me. Knowing that I live in France he said: “Santé! William, je suis très content que vous soyez venu en Finlande.” “Cheers William, I am very pleased that you have come to Finland.” It was the beginning of a friendship and an exchange of ideas and hilarious stories which has now gone on for twenty-one years. That puts me in the bracket of recent friends in Kristian’s existence. (…)

April 1992. At the invitation of Marja-Riitta Norri, Director of the Museum of Finnish Architecture, I returned to Finland as a member of the Jury of Finland Builds 8. There was still snow on the ground and ice on the sea – a long white horizon luminous at night. I thought of paintings I had done as an adolescent, one of them entitled Sibelius’ Dream. I insisted on seeing as many buildings as possible firsthand, and we ended up looking at some of them in semi-darkness! It was also a chance to visit and appreciate several buildings designed by Gullichsen, Kairamo, Vormala. I sensed a palette running from Constructivism to Le Corbusier and Aalto. “Ça vous plaît?” Kristian had asked the year before and the answer was “yes”. I was very taken with the Parish Centre at Kauniainen (1984), the inflections in plan, the various sources of light, the promenade architecturale, and of course the “wink” towards the Maison Ternisien by Le Corbusier of 1923 with its hoop shaped steel pergola. I realized that this parish complex fitted into a Nordic ecclesiastical tradition but that it also represented a particular point of view on the history of modern architecture. When I wrote the essay for the Finland Builds catalogue I gave it the title “Concepts and Continuities: Finnish Architecture of the 1980s”. Kristian took the position that he was inheriting and extending a modern architectural tradition. His own language was based upon a deep reading of past modern buildings but he felt free to take distance and to manipulate his sources with a degree of self-consciousness. (…)

April 1998. This was the centennial year of Aalto’s birth, with major exhibitions at Kunsthalle Helsinki and in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The follow-up was in Finland with a series of lectures devoted to Aalto in the old university buildings in the centre of Helsinki. I contributed an essay to the Finnish catalogue under the title “Modernism, Nature, Tradition” which looked into Aalto’s mythical landscapes. During the same trip Kristian organized a weekend at the Villa Mairea which was in every way unforgettable. One night we were all sitting around the fire when Kristian decided to give us his private tour of “the most important spaces in the Villa which people do not usually see”. These turned out to be in the basement, starting with the machine rooms for the heating, a place which Kristian sometimes visited as a child to chat with the eccentric chauffeur. It resembled the engine room of a ship. Next stop was the wine cellar which was stocked from floor to ceiling. A few bottles of fine French wine were selected and carried upstairs where the party continued into the early hours. Next, Kristian turned the staircase into a theatre for performing his own antics which as usual combined farce with deep seriousness. Out came the old wind-up gramophone from the 1930s with a record of American jazz. Kristian reminisced about his parent’s trip to the USA in the late 1930s to see Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair and about their return loaded with presents. Here then was a building tucked away in one corner of Finland, responding to its place, yet full of cosmopolitan echoes, containing works of art by Picasso and Matisse, and linked to international elites of the time. Perhaps that is another feature of the Villa in history, that it is a place where people from all parts of the world gather to enjoy the beauty of nature and to exchange ideas through the art of conversation and storytelling? (…)

The weekend drew to a close with a copious Sunday lunch. The embers in the grate were beginning to die. Talk returned to duties in Helsinki. A slight sadness set in. Then Kristian said: “William I have heard from here and there that you have some nice drawings with you.” “Oh, I am not sure that they would be of interest to you and everyone else here” I replied. “No, no, we would really like to see them”, said the group. So, we withdrew to the part of the living room with the plexiglass piano and there I laid out my “mental landscapes” one by one. They sat well in that space with the vibrations of light and shade all around, with the pervasive abstraction yet strong presence of materials, with the striations of the forest in the background. A long-focussed silence was broken by Markku Komonen: “Serious business, William.” Kristian said I should give up writing and concentrate on painting. It was one of those moments which one treasures. Aalto is the master of line, and his drawings of ruins had always haunted me. Landscape can be captured for its invisible presences through the medium of drawing and of architecture.

2002. (…) I drove from France to Finland via Sweden and the Stockholm-Helsinki ferry to pick up my drawings from the Museum of Finnish Architecture (where they had been showcased in the exhibition Mielen Maisemia – Mental Landscapes. Drawings and Paintings by William J. R. Curtis in September 2000 – installation design was by Kirsi Leiman, later Gullichsen) and spent a few days hanging around favourite haunts in Helsinki including a restaurant famous for its Baltic herrings and mashed potatoes. One evening I was invited by Kristian and Kirsi for dinner at their place. It was a greyish evening and the view from the terrace was of a flat landscape with one or two industrial harbour structures and a few passing ships. Kristian insisted on drinking outside where it was chilly. As we looked towards the grey haze he said: “You know if you half close your eyes you get a great view of the clocher of the village church tower, of the vineyard, of the market square and of the hilly slopes surrounding the village”. Always the view south, a bit like Aalto with his Tuscan landscapes transposed to Finland, although in this case the reference was to Provence where Kristian built one of his first houses fitting in under the terraces of the Var near the Côte d’Azur. No question of herrings and beer for dinner then: in fact, an excellent French meal of grilled fish with ratatouille washed down by a good wine. (…)

Spring 2008. (…) I returned to Finland with no other aim than to see friends. I went over to see Kristian in his office and he had set up a sign next to his desk which read: “Theory Free Zone”. Kristian and Kirsi arranged another weekend at the Villa Mairea and there were still one or two patches of snow on the ground: back again to the protectedness of those upstairs rooms and to the snugness of the fireplace in the living room. On the Sunday the light improved and it warmed up a bit so we wondered outside into the back garden. I recalled my hesitations about the rear façade and then Kristian said: “Well you know that this part of the building was never completed as Aalto intended? He wanted to have a sort of trellis walkway along the rear wall of the upstairs floor linking the studio at one end to the children’s wing at the other. This would have created a considerable overhang. But my parents would have nothing of it as they were afraid that we children would be running up and down and disturbing the peace, so this element was left out”. “Ah!” I replied. “That helps to explain why the transition from interior to garden always felt too abrupt to me. It also helps to explain why the linkage between the main volumes at the back always felt rather weak despite all the talk about collage”. I thought back to the first sight of the Villa in 1991 and to the discussion with the German architects when I had first been disturbed by the feeling that something was missing. Here I was again, nearly two decades further on, marking time at the Villa Mairea. Since that first contact with the Villa and with Kristian there had been so many inspiring buildings, so many rich conversations and, of course, so many jokes! “Ça te plaît, William”. “Oui Kristian, ça me plaît. Beaucoup. Un grand merci!!” ↙

WILLIAM J. R. CURTIS (b. 1948) is a historian, critic, painter and photographer and Kristian Gullichsen’s friend.