Published in 3/2021 - Sacred Space

Discourses on Dogma – Alvar Aalto and the Church

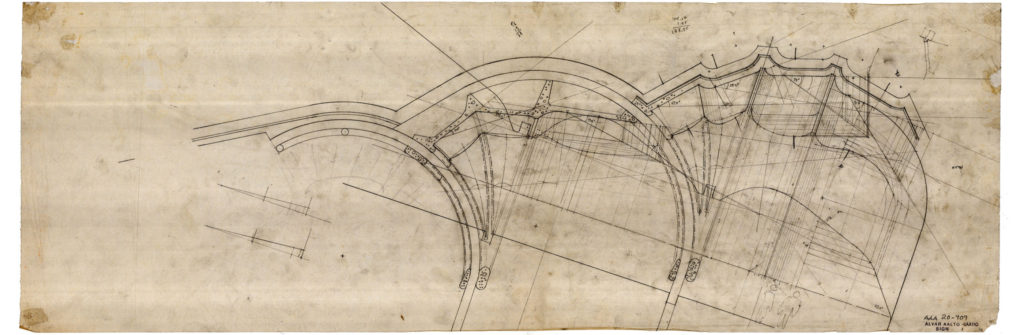

Alvar Aalto saw a parallel between his own architectural project and the Finnish national Lutheran Church’s adaptation to the twentieth century. In religion, as in modern architecture, tolerance bore more fruit than dogmatism.

The painterly play of light in the Church of the Three Crosses in Imatra, the solemn monumentality of the Cross of the Plains in Seinäjoki, and the structural lucidity of St. Mary of the Assumption in Riola are among the highlights of Alvar Aalto’s ecclesiastical oeuvre.1 Although his churches are considered an evocative subgenre of his portfolio, the relationship between Aalto’s architecture and religion has eluded enquiry. Explanations for Aalto’s longstanding collaboration with the Church have been limited to mutual opportunism. If Aalto found in the Church a patron sympathetic to many of his design ambitions – particularly the pursuit of structural and spatial complexity unattainable in civic or residential commissions – the Church found in him a famed architect to promote a public image of its own relevance in the twentieth century.

Mutual expediency cannot be discounted, but neither can it be accepted as the only source of Aalto’s kinship with the Church. Their alliance drew from a foundation of shared values. Themes such as humaneness, harmony and organic life, which are familiar from Aalto’s speeches and texts, and which have become shorthand for his contributions to modernism, were also evoked by the Church in its description of its mission in the twentieth century. The Church’s self-qualification as a corrective to the perceived rootlessness and soullessness of modernisation – by means of upholding tradition and resisting rationalist reductionism – resounded with Aalto’s architectural project, and vice versa. Perhaps the most significant congruity in the Church’s ethos and in Aalto’s design philosophy was compassion for the individual: Aalto’s empathy for “the little man” accorded with the Church’s love for the sinner.

Modernist apologias for religion

Aalto was not the only modernist to appreciate – and, subsequently, adapt and appropriate – values associated with the Church. Many Nordic architects perceived ecclesiastical projects as opportunities to critique mechanisation. The impression was encouraged and fortified by clergy, whose awareness of the ills of mechanisation, in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, was acute and raw. In Sweden, the so-called construction primitivism of Sigurd Lewerentz and Peter Celsing capitalised on the religious brief as an opportunity to refuse not just technological systems in the church interior, but mechanised building processes at large. Aalto, in turn, defied the requirement for a motorised catafalque in his proposal for a pair of funerary chapels in Denmark: “The author accepts no mechanical processes associated with the ritual (sinking or vanishing coffins, mechanically closing doors, etc. [That is Hollywood]).”2

Interpretations of Christ as an anti-establishment, anti-capitalist radical, and of the Church as a proto-anarchist institution, also animated the sustained engagement of modernists with Christianity across the arts. Poet Pentti Saarikoski, for instance, drew from the historical Jesus as a rebel and renegade.3 Public discourse was inflamed when some church officials joined the chorus. Pastor Terho Pursiainen’s Newest Testament (1969) provocatively argued that Christ should be followed not as the Messiah, God or even a saint, but as a revolutionary teacher.4

The radical “new guard” of theologians in the 1960s criticised sacral architecture for its ostentatiousness. Aalto’s churches were a prime target, condemned both implicitly and explicitly for their expensive materials, custom detailing and unabashed monumentality. Tension arises from the fact that the radical sentiment which judged Aalto’s oeuvre as vulgarly flamboyant may, in fact, have inspired aspects of its design. Aalto’s political views were non-committal, inconsistent and pragmatic, but his “anarchistically tainted social tendencies” are well-documented; did his choice of the Crown of Thorns as the theme of the stained glass in Imatra, or his refusal to connect sacral space with commercial functions in Wolfsburg, even when demanded by the local parishes, draw from the modernist discourse on Jesus as an insurgent?5

Aalto’s churches were condemned both implicitly and explicitly for their expensive materials, custom detailing and unabashed monumentality.

Faithful fellowship

Complementing the appreciation that Aalto felt for the values publicly promoted by the Church institution, he enjoyed a personal, at best even intimate, fellowship with clerical confidants. Parish priests in Germany and Italy served as “theological guides” to Aalto, supplying him with recommended readings relevant to the religious implications of his design decisions and engaging earnestly with his musings on the sacred.6 The most meaningful figures that informed Aalto’s engagement with the sacred, however, were neither other modernists nor local parish officials, but shepherds of the Finnish national Lutheran Church, especially Bishops Eino Sormunen and Martti Simojoki.

Aalto had been in close contact with Bishop Sormunen in the 1920s; contact was reinitiated by Sormunen in the 1950s. Sormunen’s critiques of commercialisation and technology, as well as his appreciation of Classical Antiquity and Christianity as the dual foundations of Western culture, resonated deeply with Aalto’s thought. Aalto’s characterisation of the ideal ecclesiastical space as “a churchly Capitolium” – a hybrid of Classical and Christian elements – comes uncannily close to Sormunen’s vision of an “inextricable and fateful pairing of Golgotha and Acropolis, of the Vatican and Capitolium. There is always tension between them, but it is precisely that which makes our culture multifarious and rich.”7 The Bishop’s son, architect Yrjö Sormunen, recalled that his father had even envisioned co-designing a church with Aalto.8

Bishop Simojoki became another close intellectual ally. He met with Aalto several times to discuss the design of the Church of the Three Crosses in Imatra; their dialogue continued until Aalto’s death. Simojoki assisted Aalto in the religious thematisation of his religious oeuvre, pondering the theological implications of the titular motif of three in Imatra and, later, the churchyard as a metaphor for Gethsemane in Lahti. Simojoki also defended Aalto to critics – for instance, he made the case for Aalto’s vision of a single cross at the altar in Lahti, in opposition to the parish’s preference for an altar painting.9 The encounters with Aalto were, for Simojoki, precious moments that afforded him valuable insights into an architect’s work and also crystallised the mutual empathy he advocated for between the Church and artists.10

A monument to uncertainty

Despite being senior leaders of a national religious institution, both Sormunen and Simojoki took measures to dissociate themselves – and, thereby, the Church – from unyielding dogmatism. In opposition to the moralist theologies in favour in the 1930s and 1940s, Sormunen promoted the conception of an open folk church, which unhesitatingly offered its grace to all. His calls for acceptance were no doubt informed by the tension in his own life, where, “unable to deny the allure of the humane and the worldly”, he was prepared to accept the resultant religious conflict.11 Simojoki occupied an analogous position, having branched out from the strict Pietism and “cultural antipathy” of his youth to the promotion of a socially and culturally accepting dialogue between the worldly and churchly realms, which underscored the Church’s mandate to serve all, not just its own members.12

Bishops Sormunen and Simojoki regarded the Church of the Three Crosses as a standout, which reflected the tolerance they espoused in the national Church.

Interestingly, both Sormunen and Simojoki regarded the Church of the Three Crosses as a standout, which, in addition to its architectural merits, reflected the tolerance they espoused in the national Church in the twentieth century. Simojoki, who consecrated the building, interpreted it as a monument to uncertainty: its lyrical interior mirrored the “many doubts and contradictions” of the contemporary mind, and rid the self-righteous “of all their assumptions”. In Simojoki’s reading, the design consciously opposed the “worst possible violation to our Saviour’s cross: isolating it among a select few”, and, instead, invited in “even those who did not consider the religious question an existential matter”.13 According to Sormunen, the design successfully “constituted part of the worship”, although he remained uncharacteristically mum on the reasoning behind his remark.14 Given how often, in his other writings and speeches, Sormunen had underlined the fact that life gives more questions than answers, it is not implausible that he, too, would have likened the building to a doubter’s prayerful murmur more than an impassioned sermon.15

In particular, it was the incongruity of the inner and outer shells of the Three Crosses that was read as an architectural metaphor for uncertainty. The dark hump of the roof suggested nothing of the airy, vaulted ceiling inside, and the upright exterior facades concealed the way in which the inner surfaces, even glazing, leaned and fanned inwards. “The ethical cornerstone of Modernism: the distinction between structural and non-structural members” was blurred, and various opposites – inside and outside, wall and ceiling, surface and skeleton – suspended from clear definition.16 The resultant idiosyncratic sensibility, somewhat Baroque in register, was interpreted by Simojoki as an architectural manifestation of irresolution, and an acceptance thereof. “The architecture of this building”, he preached, “speaks in its own way of how the Church of the God of grace does not push away people for not posing only the kinds of questions the Church is familiar with.”17 In complicating the relationship between typical architectural opposites, he suggested, the Three Crosses evaded perspicuity and accepted perplexity – just as the national Church ought to.

The Doubting Thomas of modern architecture recognised the Bishops as brothers-in-belief.

Doubting dogma

A symmetry underlay the communion between the two Bishops and Aalto. Whereas Sormunen and Simojoki interpreted Aalto’s architecture in light of their own theological and church-political views, Aalto regarded their thought as a reflection of his position in the Modern Movement. Their rapport was rooted in the shared critique of inward-looking dogmatism in architecture and religion, respectively – while Aalto berated the unrelenting authoritarianism of International Style modernism, the Bishops cautioned the Church against sanctimoniously restricting itself to a select few. The thematic overlap crystallises the Church of the Three Crosses’ essence as a modern religious building: it challenges rigid doctrinairism in both religion and architectural modernism.

While accounts of Aalto’s perceived exceptionalism with regard to modern architecture must be received with a grain of salt – especially as the assumed homogeneity of “mainstream modernism” continues to be questioned in contemporary scholarship – his architecture has long been typecast as an outlier of sorts. Aalto’s simultaneous belonging to and departure from “the Masters of the Heroic Period” has informed characterisations of his oeuvre as a critical, otherist or even anti-modernist brand of modern architecture. His apologia for “the often disdained sceptical world view”, explicated in a seminal speech in 1958, has fuelled interpretations of his dissidence: as a sceptical modernist, he operated within and for the modern movement but was forever inclined to question its self-proclaimed truths. Exalting scepticism as a type of radical acceptance – the capacity to simultaneously entertain conflicting conceptions of the world – Aalto himself quoted Simojoki: “Christianity should not isolate itself and remain only amongst its own, for it belongs to everyone: both those who believe and those for whom nothing is holy.”18

The quotation was not merely a flippant appropriation of a religious sermon into a cultural theory, but a grateful acknowledgment of the mutual affinity between Aalto and his priestly supporters – and by extension, between him and the Finnish national Church. Sormunen’s and Simojoki’s appeals for broadening the reach of the Church matched Aalto’s calls for modernism to become more willing to deviate from its self-defined orthodoxy. The Doubting Thomas of modern architecture recognised the Bishops as brothers-in-belief, who not only empathised with, but shared his scepticism towards dogmatism. ↙

SOFIA SINGLER

Architect, PhD (Arch.), Fellow of Homerton College, Cambridge. Her research interests lie in the history and theory of modern architecture, with particular focus on ecclesiastical architecture, Nordic modernism and Alvar Aalto.

1 For a comprehensive and beautiful compendium of Aalto’s churches, see Jari and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen: Alvar Aalto Churches (trans. Gareth Griffiths and Kristina Kölhi), Rakennustieto 2020.

2 Alvar Aalto & Jean-Jacques Baruël: ”Centralkirkegaard, Lyngby–Taarbæk commune”, (unrealised). Drawing no. 25-176, n.d. Alvar Aalto Museum Archives.

3 Arto Köykkä: Sakeinta sumua käskettiin sanoa Jumalaksi. Uskonnollinen kieli Pentti Saarikosken tuotannossa, PhD dissertation, University of Helsinki 2017.

4 Terho Pursiainen: Uusin testamentti, Tammi 1969.

5 Göran Schildt (ed.): Näin puhui Alvar Aalto, Otava 1997, 163.

6 See i.e. Susanne Müller: Aalto und Wolfsburg. Ein skandinavischer Beitrag zur deutschen Architektur der Nachkriegszeit, VDG 2008.

7 Alvar Aalto: untitled project description. Alvar Aalto Museum Archives; Eino Sormunen, Lännen syksy, WSOY 1951.

8 Letter from Yrjö Sormunen to Göran Schildt, February 7, 1993. Alvar Aalto Museum Archives.

9 Mauri Malkavaara: Ristinkirkko, Lahden seurakuntayhtymä 1998, 47–49.

10 Martti Simojoki: ”Oma kirkkoni”, in Meidän kirkkomme. Seurakuntien paimenet kertovat kirkoistaan (ed. Aimo Vuokola), WSOY 1979, 5–6.

11 Antti Alhonsaari: ”’Selvyyttä kohti’. Kysymyksiä Eino Sormusen kulttuurityön ääreltä”, teoksessa Eino Sormunen. Tutkija, esipaimen, kulttuurikriitikko (eds. Veijo Saloheimo, Hannes Sihvo & Alpo Valkeavaara), Karjalaisen Kulttuurin Edistämissäätiö 1990, 84–85.

12 Juha Seppo: Arkkipiispan aika. Martti Simojoki II, WSOY 2015.

13 Record of Consecration, Church of the Three Crosses, conducted by Martti Simojoki, Bishop of Mikkeli, September 28, 1958. Imatra Parish Archives.

14 Eino Sormunen: Kirkko ja seurakuntakoti. Johdatus nykyiseen kirkonrakennustaiteeseen, Suomalainen kirjakauppa 1962, 23.

15 Päivi Huuhtanen: ”Eino Sormunen kirjailijana, eli Taru Sormusen Herrasta”, in Eino Sormunen. Tutkija, esipaimen, kulttuurikriitikko (eds. Veijo Saloheimo, Hannes Sihvo & Alpo Valkeavaara), Karjalaisen Kulttuurin Edistämissäätiö 1990, 107.

16 Demetri Porphyrios: Sources of Modern Eclecticism. Studies on Alvar Aalto, Academy Editions 1982, 4–5.

17 Record of Consecration, Church of the Three Crosses. Imatra Parish Archives.

18 Alvar Aalto: ”Mitä on kulttuuri?”, in Näin puhui Alvar Aalto (ed. Göran Schildt), Otava 1997, 15–17.