Interview with Bijoy Jain

In February 2021, the fourteenth Alvar Aalto Medal was awarded to Bijoy Jain, the director of the Indian architectural office Studio Mumbai. In their work, the office seamlessly combines architecture and craftsmanship and attention to local conditions. Kristo Vesikansa interviewed the winner.

Past Alvar Aalto Medallists include James Stirling, Jørn Utzon, Tadao Ando, Alvaro Siza and Glenn Murcutt, among others. How does it feel to be part of the continuation of these respected architects?

Of course, it is a privilege and an honour to be in such respected company of architects, just in terms of their empathy and affection, more than just their philosophy; how they have conducted themselves through their journey.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the award ceremony was held at the Finnish Embassy in New Delhi, designed by Raili and Reima Pietilä in the 1980s. What kind of impression did this building give you?

It is such a beautiful building – actually, a complex of buildings. I remember seeing photographs of it; this was before I was in architecture school. For me, it was just a wonderful opportunity to visit this building. It is like being in Finland in Delhi; it is quite impressive spatially and experientially. I am also very fond of the Pietiläs as architects. They developed their own discipline and expression, continuing on from Aalto in some ways. I think they are both Bauhaus in that sense.

The Pietiläs explained that, when designing the Finnish Embassy, their intention was to create a building that would act as a link between Finland and India. Hence, the building contains references to natural features and cultural conditions from both countries. Does this kind of approach make sense to you?

Absolutely. It is wonderful that geographies can, in some way, meet. We are just charged with the potencies of both these cultures. I like the idea of a palimpsest, the making of a third one, which is not one or the another. When I went to see the swimming pool and sauna of the Finnish Embassy, at that moment I felt completely displaced, I felt as if I was completely inside Finland. Another thing that struck me was the openness and hospitality, which is very much present in the space. While it is an embassy building, it also manages to be an open building, which is very particular to Finland. The culture is apparent in the space.

You have studied in the US, worked in the UK and lectured around the globe. At the same time, it is almost impossible to distinguish your projects from the geographical, cultural and social context of India.

I never thought of it in the way it has been seen. Of course, travelling, exposure, all of that becomes a very essential part of a living experience. What I have begun to understand is that it is not just an India-centric thing or a Finnish-centric thing. We share values that are common globally, and tapping into those shared experiences or values makes it something that we call global. It is not about style or form, it is about the ethos that we share electively across the continents.

Do you think your architecture is Indian, Asian, Mumbai, global or something else?

I have never thought of it that way. The moment you do that, you kind of limit yourself. I am working in France, Italy, Japan and other places right now. For me, it is not about what is Indian, what is American, or what is Finnish. We share common things. Somehow the space can provoke or evoke that quality to be drawn out.

As the name of your studio implies, you live and work in the metropolis of Mumbai. How is the impact of this local context reflected in your work?

I find it very invigorating in that it is very charged and interesting. Previously, my studio was in the countryside, and now my studio is in the city. If I observe my actions, I have done exactly the same things in both places. For me, it is just the charge of the environment you are tapping into, and you can draw from that, take things from that or participate in that, which is what we did earlier as well. The nature of the disciple of practice has remained exactly the same in terms of tuning and centring.

How is working abroad different from working in India?

The approach is the same. The methodology is what is fine-tuned to suit the location because the location demands a certain set of parameters that have to be met to move forward. It utilises the same infrastructure, and it is only a question of how that infrastructure is organised or how it is calibrated between the end number of agencies or entities and how you maintain the conversation. For myself, the important part is to remain in that flow. If you are in that flow, then participating is much simpler. Each of these places will pose its own difficulties, obstacles or challenges that need to be answered culturally, economically, climatically, etc. It is a matter of tuning in to those anomalies. You have to tone yourself. I enjoy that.

Studio Mumbai’s working method is quite exceptional, at least from a European perspective. You employ both architects and craftsmen who are responsible for realising the projects. What was the reason for creating such an organisation?

It was because we architects don’t know everything. To cite an example, I have to design a door and a window for a winery in the South of France. Sure, I know how it works here, but I can’t just take that and superimpose it directly. There is already a very deep embodied cultural knowhow. Why would I not tap into that resource to bring me up to speed? Taking that to another level is when the dialogue takes place. When you bring that together, something else possibly occurs.

In modern society, architecture, crafts and the arts have evolved into separate disciplines. In your work, however, they combine in a fascinating way. For example, your installations have been exhibited in art galleries. How do you see the relationship between architecture, craftsmanship and art?

I don’t think much has changed in that sense. If you look at the Renaissance or Pre-Renaissance or even go further back in time, artists made paintings, designed buildings and wrote about the sciences, too. By doing these other things, I am not restricted to that narrow gauge into which we have jacked ourselves. For me, it is a way to practice the core essence of architecture. Making a building is not difficult, but how do you charge the building with a conceptual idea? How do you charge that space with that kind of energy, tactility? Aalto, Pietilä, Borromini and Siza were able to charge their buildings with this other haptic quality. The idea to practise all these diverse methods and this way of making is to remain in that charged field. There was always the intention that these things we do will be around for a period of time, and if I visit one of them, I want to be able to experience for myself that it is charged, it is present in time, it will shape and move, it is a breathable artefact. For me, it is an interest. That being said, it is not a question of a hand, machine, technology, or no-technology – it has nothing to with that. You can use whatever resources are available, as long as those resources can be used in a way that can be engaged in a haptic way.

In addition to buildings, you have designed numerous pieces of furniture. Do you see a fundamental difference between the design of a place-specific building and a movable piece of furniture?

It is all space in the end. It all engages the human body in one form or another. In furniture, the moment you make a modification of 4 mm there is a big shift, while in a building you can make a modification of 4 metres. It is about understanding tolerances. You have a better understanding of tolerances built into that dimension. It is the same way you train your body, macro-muscles or micro-muscles.

You have said many years ago that, when designing a building, the programme is secondary. This differs significantly from the way most architects think and work in Finland. Could you explain in more detail what you mean by this argument?

Eating, sleeping, writing with a pen on a desk, sitting at a computer, looking out the window – that is a given. That is what we do, right? For me, typology is important; that is the core essence of space and the diverse ways it can be occupied over a period of time. The programme will change no matter what happens. If you make it absolute, then it becomes a dogma. When the space is inclusive to receive an end number of different ways, it can, potentially, be occupied. For me, that is the programme of the project. It is how you inject it, how you infuse it with the idea that it can traverse time, modify itself and accommodate itself, that something can come on top of it, and it is okay and that the project is not absolute.

Do you create different scenarios for how the building will be used in the future?

What remains at the centre of all the work is locating and anchoring to something that is embedded and allows us to have a ground. For me, the only precondition is that it is grounded in gravity. The building will assemble and dismantle itself in time. But the potential we have is to put something in there that allows for a reassembly of something at a later point. For me, that is the essence of architecture.

Your architecture is largely based on the characteristics of the materials. In recent years, materials have also played an increasingly central role in Finnish architecture, mainly due to the debate on sustainability and carbon neutrality. What are your criteria when choosing materials for the projects?

As human beings, we are also material; we are made of water, air and light. We are just an energy field of water and light that is vibrating to give us form. If the materials can mimic that or emulate that, fabulous. I am not thinking of sustainability as an idea of trying to save something, but more of the idea to retain one’s energy. How do you, in the shortest time, get the greatest distance? The materials also have to include this idea of speed, distance and time in the way that they will evolve, disassemble and dismantle themselves to be reassembled. It is not about finding natural materials or unnatural materials or any of that. Our actions are embedded in materiality, no matter what the material is; our action is required to enter into that. For me, that is really the important thing, the charge you embed in that field.

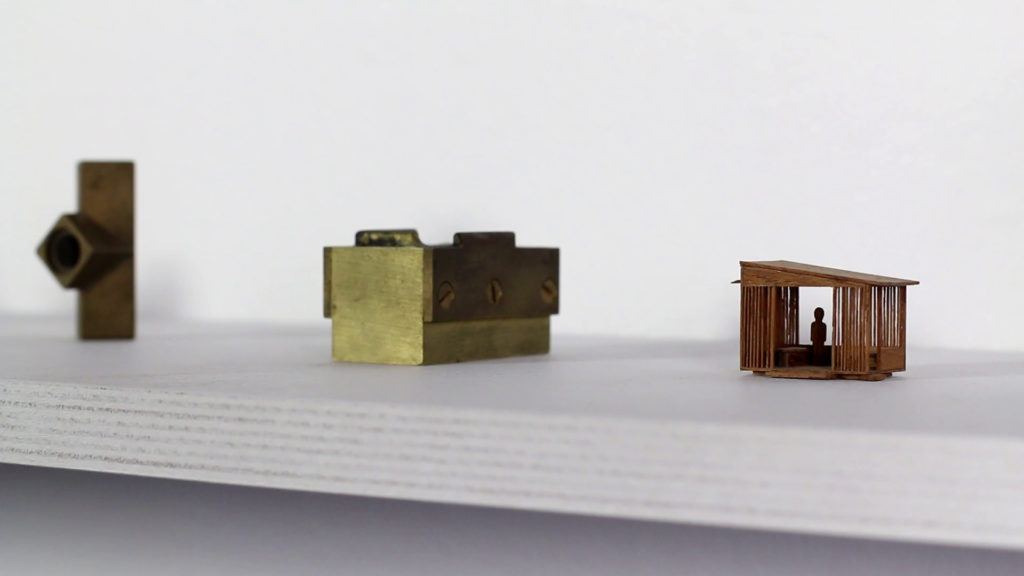

Your exhibition will open during the spring at the Museum of Finnish Architecture in Helsinki. What will be your message to Finnish visitors?

I am just sharing my space, what I do and how I do it, and the visitors are invited to be part of that space. It is not a solution, it is not a direction, it is just a space that allows a certain intimacy for people entering into that space. It is more like my studio in that space. That is what I can share. There is no other message beyond that. ↙

The Alvar Aalto Medal, established in 1967, is awarded every few years as a recognition of a significant contribution to creative architecture by the Alvar Aalto Foundation, Finnish Association of Architects (SAFA), City of Helsinki, Foundation for the Museum of Finnish Architecture and Architecture Information Finland and the Finnish Society of Architecture