A City Out of Nowhere

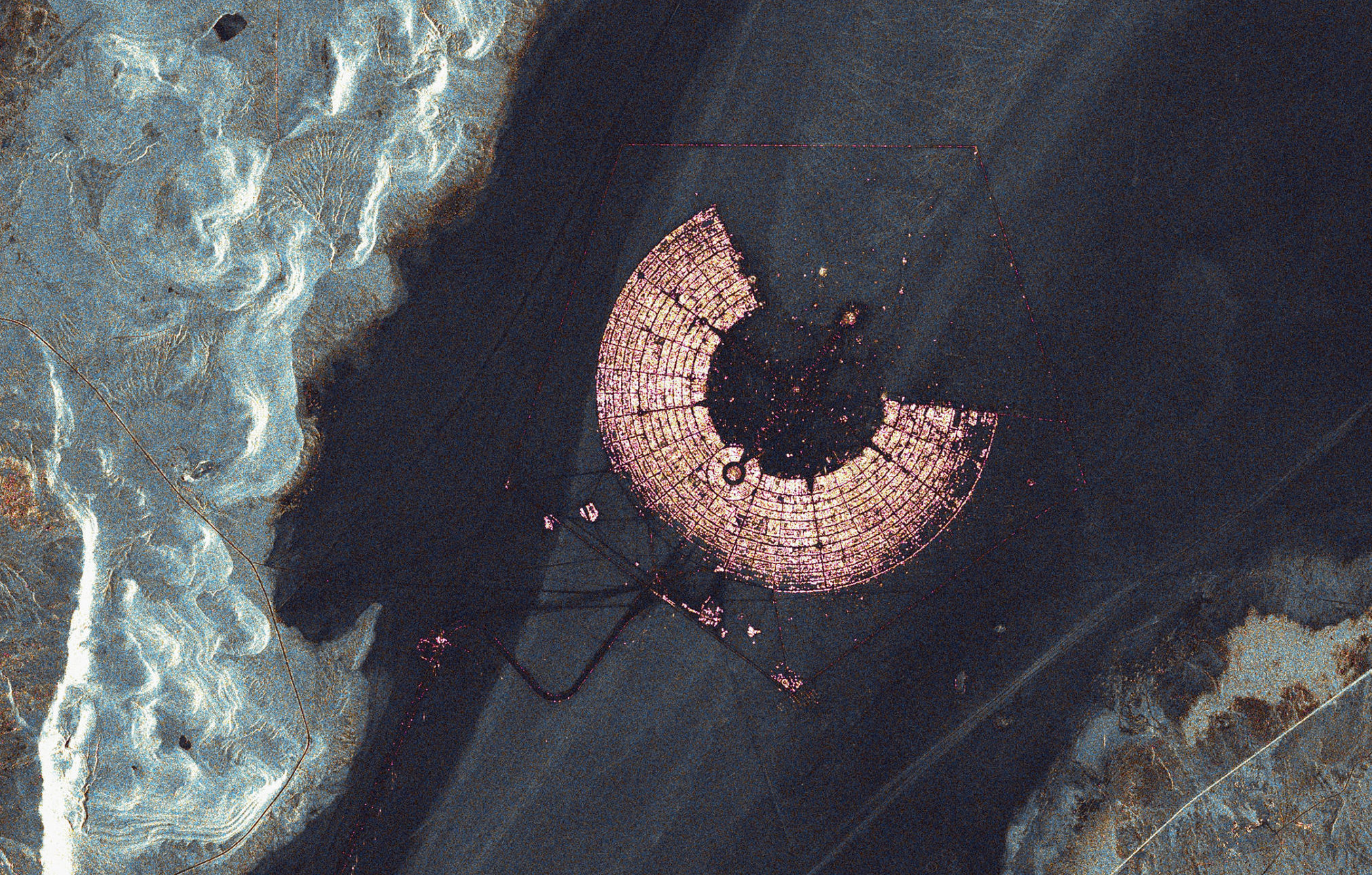

Every year, in the first week of September, a C-shaped city of 70,000 inhabitants is created in Nevada’s Black Rock desert. Every item needed for and at the city is transported there by the organisers. The participants, known as the Burners, organise themselves into a series of camps on their arrival. No form of self-expression is out of place here, and humanity in all its diversity is always on display. You choose what to wear or whether to wear anything at all. Huts, tents, buildings, random structures and fantasies are created, and after the week is over, they’re destroyed and tidied away – or burned down.

First organised on a California beach in 1986, Burning Man has latterly emerged into the mainstream, not least thanks to the extensive coverage the event receives on social media. What was once a small gathering of like-minded people has evolved into a global cultural institution that sees bohemians, electro musicians, artists and free spirits rubbing shoulders with film stars and startup millionaires. In the ironically-minded debates surrounding popular culture, the festival has often been dismissed as a male-dominated rite of passage for the tribally insular tech crowd, but this entirely self-organising city that is built in the desert by hand in a matter of days and offers total freedom from the constraints of everyday life, also tends to attract genuine interest and curiosity.

It is certainly no coincidence that big tech firms have embraced the festival. In the 1970s, radical subcultures and spirit quests were integral to Silicon Valley’s social makeup. By the 1980s, the United States may have entered the Cold War era and begun to chart a more conservative course in terms of its financial policies, but American artists, academics and bohemians had not given up on the idea that the restrictions imposed by the country’s class and economic systems could ultimately be shaken off. Ideologues like Apple founder Steve Jobs drew strength from this notion of personal liberty as they worked away in their garages, setting up their fledgling business ventures. In that sense, the present-day fascination big businesses palpably hold for Burning Man is all part of a more longstanding continuum. Many companies, particularly those operating in the creative, digital and design industries, have come to view the festival not only as a brilliant networking opportunity but an experimental and creative testing ground.

Despite the freedom it offers to Burners, the temporary city at Black Rock would not be possible without a great deal of careful planning. The revellers arriving in a never-ending stream of cars that stretches into the horizon take their places on the site in a clear and precise semi-circle formation. The area is bisected by a series of avenues and divided into sectors and theme camps, each with their own distinct purpose. Waste and traffic management, energy generation, logistics, cleaning and other key infrastructure services are managed through mutual agreements and volunteer efforts. Over time, the site has repeatedly been expanded to accommodate the festival’s growing popularity. Since 2000, a temporary temple has been built in the middle of the C-shaped arc each year, with artists as well as architects invited to design the structure. Though the temple, which is always burned down at the end of the festival, does not reference any world region, there is something fundamentally pagan about the festival’s creed: the eponymous Burning Man is a 12-metre tall effigy that’s also torched when the week’s festivities are over.

The festival’s temporary, fantastical, futuristic structures have increasingly proved a draw for architects too. In 2018, Danish architects BIG built The Orb, a floating mirrored sphere, 25-metres in diameter, which was intended to reflect planet Earth at a scale of 1/500,000. The photo-friendly silver globe was captured in countless sunset snaps on Instagram and Snapchat posts. This is definitely one way to attract global visibility for architecture.

A few Finnish design practices have also blazed the trail and participated in the festival. In 2017, Lundén Architects took part in the Space on Fire project run by a 50-strong multi-disciplinary team from Finland. The Cosmic Egg, a wooden dome constructed in the desert, was an opportunity for the architects to experiment freely with the algorithm-generated structure without having to worry about building regulations or planning consents. Last year, JKMM Architects took part in the Metamorphosis-themed festival, adding a quintessentially Finnish feature, a traditional wood-fired sauna, to the revelries. Created using a deceptively simple wooden structure, the Steam of Life welcomed around 1,000 bathers during the festival run.

Although the 2020 festival has now been cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic, Burning Man will no doubt make a return eventually. The now-enormous temporary city has recently attracted criticism over its environmental record and the sense of elitism that has crept in as the festival has become more successful. And yet it has also shown itself to be capable of demonstrating what people can achieve when they work together as well as offering us experimental glimpses of something new and different emanating from beyond mainstream society. The interesting thing about Burning Man as a contemporary phenomenon is how it manages to reflect our attempts at self-realisation, whether through art, through collaboration or through other forms of creative self-expression, which are present but often remain hidden in our high-tech society. What it also shows is how individual liberty and a deep commitment to tolerance can engender order and generate social capital. We are all den-builders by nature, it seems. ↙

Cosmic Egg

Lundén Architecture

Eero Lundén, Ron Aasholm, Matti Pirinen

2017

Steam of Life

JKMM Arkkitehdit

Samppa Lappalainen, Marcus Kujala, Hannu Rytky, Päivi Aaltio

2019