Editorial 2/20: Fences and Thresholds

Today’s society has contradictory attitudes towards rules and liberties. Some people call for individuality, agility, smoothness and deregulation of norms, whereas others want to rely on the stability of the system. Unnecessary bureaucracy is not wished for, but, simultaneously, people hope that society takes responsibility in large matters. The need for the latter has been emphasised due to the virus pandemic during the past few weeks. However, even in normal conditions, there are also many ongoing global and technological changes that must be responded to. New rules and amendments to existing statutes and agreements are also required.

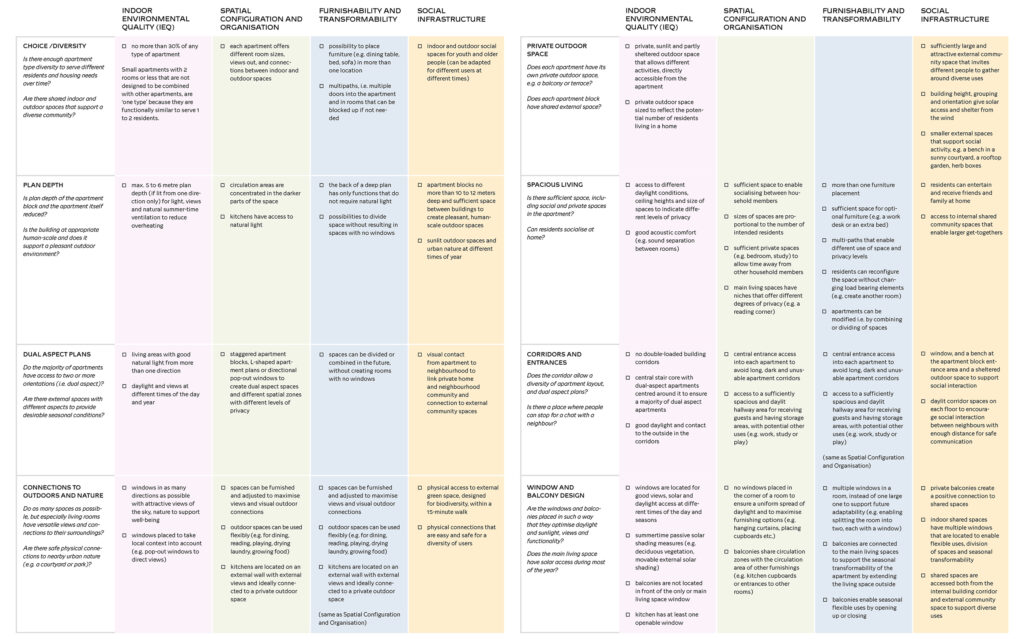

We often hear designing architects say that “the plan stipulated”, the “Building Control demanded” and the “maintenance and service traffic required” certain matters, or that protection, energy and accessibility regulations “posed special challenges” to the project. Consequently, we are quite used to the fact that construction is regulated in many ways, subject to a permit, restricted by various factors – and we probably understand fairly well why certain things have been steered in the first place. Regulations and instructions are often also drawn up by architects.

Despite this, those who work within architecture often note that well-meaning regulations can create unclear situations. If the bar is set low, a minimum becomes normal. If there are very detailed regulations, a minor point can become a threshold element. Contradictory goals are also often concretised in construction and land use. It is clear that from time to time, statutes must be updated and it must be discussed whether they function adequately at present. At the same time, it would be worthwhile pondering in which framework of norms, rules, agreements, facts, illusions or practices architecture or planning is carried out.

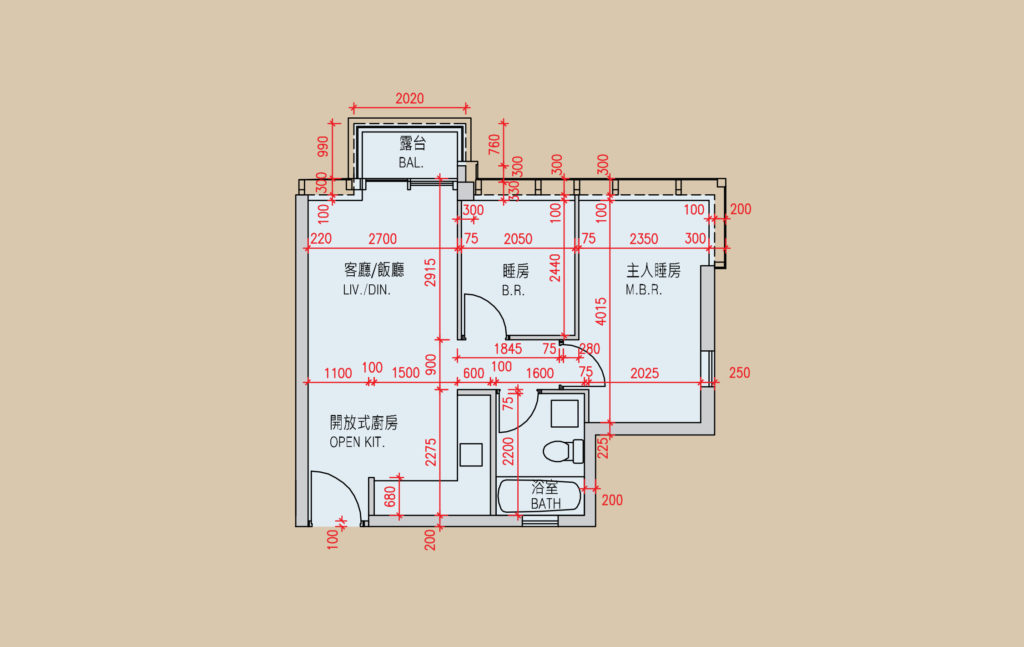

Quite recently, it has been discussed whether statutes produce weaker built-up environments than intended. In Finland, for instance, the much discussed windowless bedrooms in new residential buildings appear to be a drawback at least in the history of modern design, which has attempted to move from dark and cramped spaces towards space and light. On the other hand, throughout history, those who have been able to pay for space and light have always got it. Consequently, this is not only about the design norms or giving them up, but about economic principles and the rules of the game approved by society.

Rules and regulations are a question of which values we wish to raise above opinions – or economic profit, for instance.

It is also possible that, as in other areas of life, people are not necessarily interested in expert opinions. For some, a darker sleeping space is suitable as a home cinema or a computer gaming space, and the other does not want a proper kitchen or laundry drying space. The third perhaps only wants one large space and no linen cupboards or internal walls. Perhaps housing is a fitting example of the changing values and need for spaces. But at which stage does this become a matter of sliding towards small and expensive square metres instead of being a matter of making the housing supply more versatile?

In fact, it is a question of which values we wish to raise above opinions – or economic profit, for instance. Rules and regulations that aim at creating a good environment cannot represent noble elitism. They have been meant to maintain and achieve long-term well-being and equality. It is also true that currently, not everyone can receive as ’good an environment’ as we would like to design. We cannot influence the increasing inequality of society in all respects.

However, architects so far are probably more influential in the planning of land use, residential areas and dwellings than a person who buys a new dwelling, for instance. This is also about communication – having, as a minimum, a shared understanding of the aim of the rules. ↙