Reclaiming Expertise

Architects can exert an influence on what is regarded as sustainable construction. It is also obliged by their code of ethics, but do architects understand their responsibilities?

An architect walks past a construction site. What does she see there? Behind the fence, the workers are handling construction products, almost all of which are harmful when they end up in the environment. As a matter of fact, the products are there already. The construction workers wear protective clothing. Even so, people will move in here soon.

Do architects realise that buildings are being made of harmful materials and material combinations whose combined effects are unknown? Do they understand that those materials will accumulate in the environment? The complex structures of contemporary buildings cannot be maintained endlessly. Buildings will soon be at the end of their lifecycles: unusable depositories of hazardous waste, waiting to be demolished.

Are architects capable of concluding what human and social problems will arise from this? By the end of a building’s lifecycle, the building is making its users ill: people are losing their health. When an expensive building cannot be used any more, people also lose their investment. In our system based on the transfer of income, all of us are, indirectly, payers of poor building practice.

What kind of thoughts do architects have when they glance at news headlines about microplastics, toxic substances, corruption and trade secrets for contents of products in the construction sector, contradictions in bureaucracy, or the notion that the adverse effects caused by buildings are considered a national health crisis in Finland? Do they understand that through their own work they are participating in causing such matters? Or are they just “busy at work” and have stopped thinking for themselves?

“It Isn’t the Architect Who Decides on These Things But the ___________”

As long as there is no proper definition for sustainable construction, it can be just about anything. And it currently is.

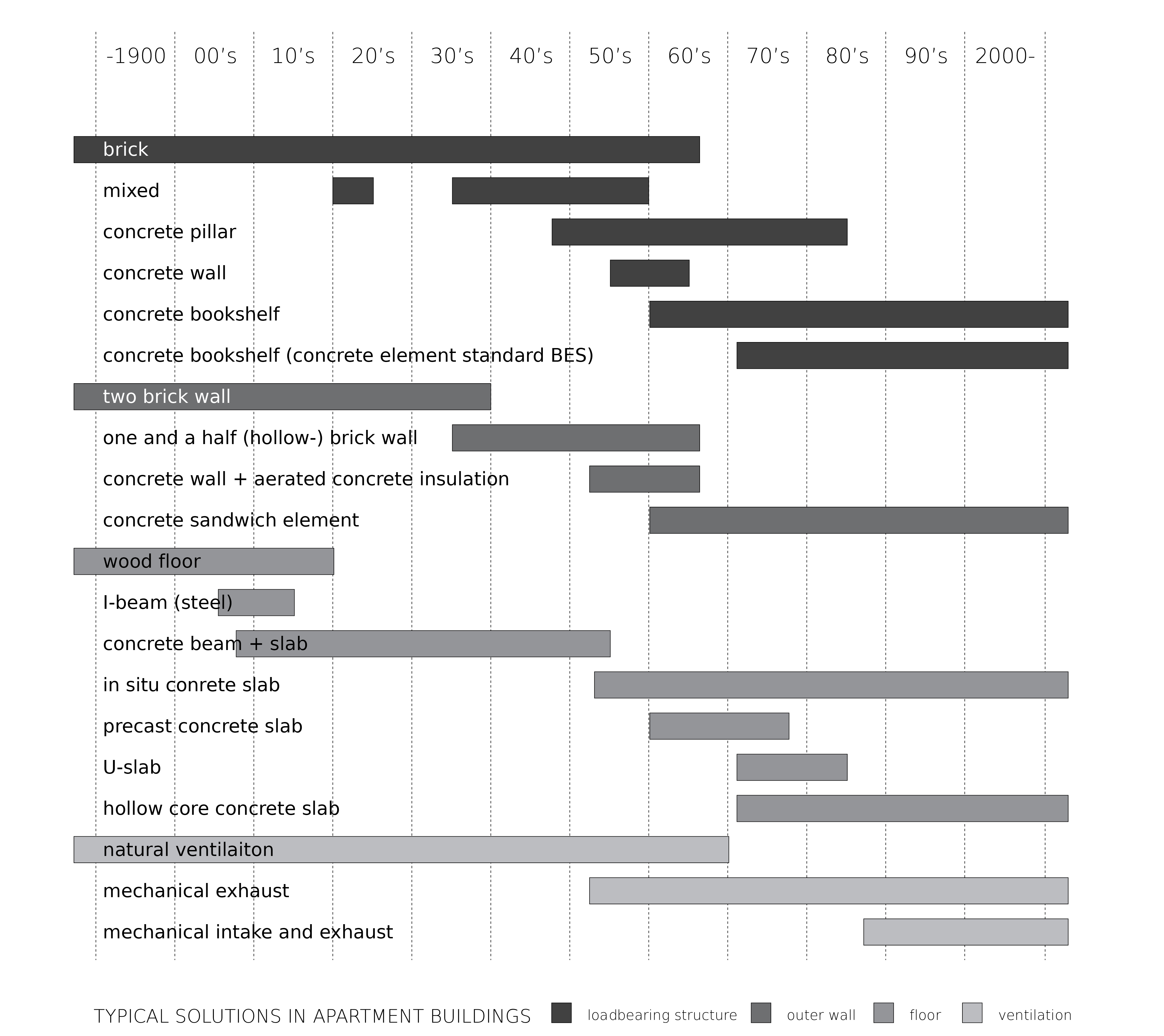

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Finnish construction sector did not worry about the future. Construction activities were based on efficiency, not quality. Lifecycle thinking and the design of disposable buildings began.

All the same, this building practice was never really abandoned, but construction is still carried out exactly in the same way. However, poor building practice has transformed into something good on paper: ever since sustainability became the general objective of the Land Use and Building Act of Finland, all construction that adheres to the building regulations has been, by definition, ‘sustainable’.

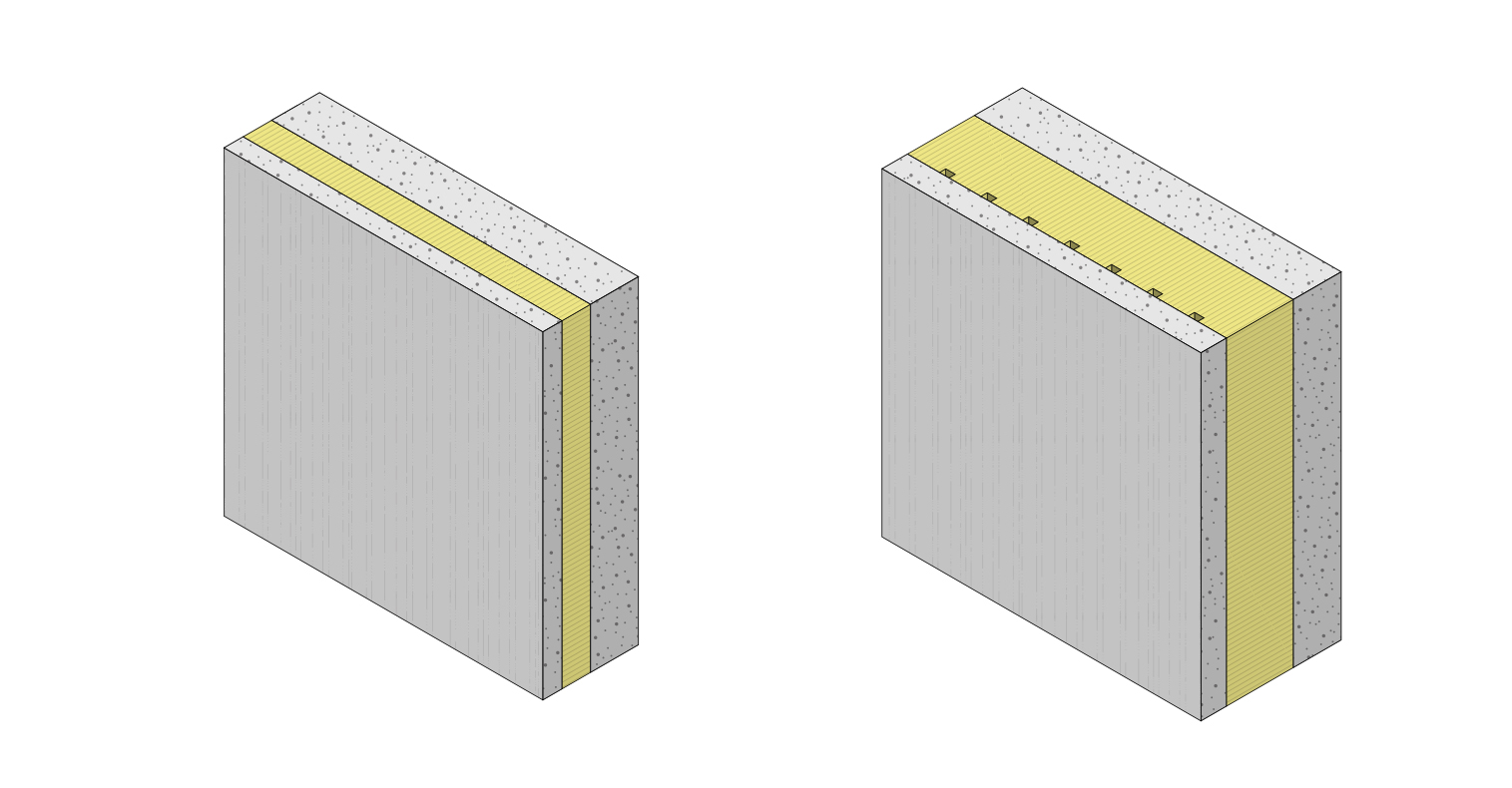

Practicing architects should be able to see that the typical wall structure is still exactly the same as before the launch of the sustainability regulations.

Laypersons do not read plans and designs, and they do not examine the backgrounds of the Land Use and Building Act. Instead, practicing architects should be able to see that the typical wall structure is still exactly the same as before the launch of the sustainability regulations. Architects would be capable of figuring out the absurd circular reasoning in the Land Use and Building Act: sustainability has been standardised, resulting in the construction of unsustainable buildings; but as these buildings conform to the regulations, they are, paradoxically, regarded as sustainable.

Do architects rely on their own expertise and the knowledge in their field regarding sustainability, or have they handed over their expertise to other people and ended up in the position of an operator or layperson? Contemporary construction has generated new experts whose tasks are to model, calculate and explain new standards of sustainability. Do architects dare to point out contradictions in their models, calculations and explanations?

Baboon Footprint, Greed-house Gas Emissions, Spiral Economy, Unsustainability…

There was perhaps a time when architects knew their materials. Today, they choose items from dropdown menus and fill in forms, using the presumptions of people in other fields with regard to which materials should be used for the construction of buildings and why.

A carbon footprint is a reading that is said to indicate the volume of greenhouse gas emissions caused by construction activities. Nevertheless, a carbon footprint does not convey any information on the physical qualities of construction materials or buildings, especially their harmfulness. For instance, industrial waste can have a small carbon footprint when it is reused in the walls of a residential building.

A carbon handprint is a reading that is said to indicate positive climate impacts created by construction activities. The name suggests that a large carbon handprint could compensate too large a carbon footprint. However, a carbon handprint is, in practice, increased by adopting measures that are trivial to the whole – for instance, by designing a green roof for a parking facility.

Products used by today’s construction sector are too complex to be recycled.

Recycling and a circular economy are just rhetoric from the perspective of genuinely sustainable construction. Firstly, products used by today’s construction sector are too complex to be recycled. Secondly, the considerable amount of energy required for recycling does not circulate. Thirdly, even if we were to recycle everything we now use, it is not enough if the economy grows: the virgin feedstock required by growth must always come from somewhere.1 Furthermore, all recycling systems created by human beings are incomplete and temporary.

Finnish-speaking architects probably get confused by the fact that both recycling and downcyclinghave been translated into Finnish as ‘kierrätys’. One might think about recycling as a process in which glass bottles are melted and blown into new ones. In reality, recycling also means the burying of construction waste in the ground in order to function as a base for a road, for instance.

Contemporary buildings have occasionally been compared to spacesuits: according to calculations, both are energy-efficient and clean, but in practice they represent the waste of energy and resources. A spacesuit can also be a dystopic outcome of contemporary construction. Architects do not understand the consequences of their work and do not correct their mistakes. On this basis, someone else gets a chance to create new business activities. The expertise is gradually taken away from architects, and as they believe in development and regulations, they adapt to the situation. Soon architects will no longer be required.

“But At Least It Looks Good”

Instead of changing building practice, only the way construction is discussed has changed. Newspeak has caused confusion in the basic terminology of the field. According to the Finnish Architectural Review (2/2019), “[t]he first school project in Finland utilising solid wood construction” was completed in 2018, and was built from CLT. Later in the same article, it is discussed whether the frame of the building could be made completely out of wood. This wooden structure is no longer called by any name: the term solid wood has been hijacked for a disposable, mixed structure of glue-laminated timber. The embarrassing confusion of terms concretely affects the building stock. Two years ago, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland announced that the wood content of new Finnish “wooden buildings” was only 16–32 per cent.

According to the Finnish Association of Architects’ Arkkitehdin ammattieettiset periaatteet (2003, the architect’s principles of professional ethics, in Finnish), the main ethical objective of architects is to maintain the credibility of the profession. Architects may not stain the reputation of their field. The key is to act in accordance with the values of the field. The first value mentioned is sustainability: architects “may not accept an assignment or participate in a project that weakens the quality of people’s living conditions or the quality of the environment”.

We know that both the quality of people’s living conditions and the quality of the environment have now weakened, due to buildings. Consequently, the value of sustainability has not been adhered to. This way, the credibility of architects has also declined. How have been the attempts to restore it then?

Apparently they are yet to be attempted. Architects have so far turned a blind eye on the large-scale problem in which they are complicit and which they could help to solve if they wanted to. There have been very few public statements, and even they have been spent on matters trivial to society. Unsustainable buildings have even been defended if they have been works by renowned designers or have represented popular styles.

It must be painful to see one’s lifework or a building that one admires being demolished. Outcries of a “new wave of demolition” is a symptom of this pain. However, an unsustainable building will not become sustainable after it has been “repaired”, i.e. when it has been demolished down to its frame and rebuilt as unsustainably as the first time. In public discussion, contemporary construction presents itself as a 50-year-long period of failed experimental construction.

Feedback is asked for of the general public with regard to matters like usability and aesthetic choices: do they like to use the building, is the building interesting and does it look good, and does it look nice in the cityscape? Surely, these matters are important, but they cannot be the most important.

What Can Architects Do?

Which is worse: a situation in which architects have not found out what materials are they designing buildings out of and what problems they may cause, or a situation in which architects have indeed found out about the materials but do not change their actions? On the basis of the architect’s principles of professional ethics, these are equally bad, as architects should, in any case, be active, critical acquirers of information, who boldly put it into practice.

A bulletin, Etiikan luonne ja käsitteet (features and concepts of ethics, in Finnish), has been appended to SAFA’s principles of professional ethics. It encourages architects to ponder what is true and what has just been agreed on. Which matters are part of the physical reality of the planet, and which are just related to the current national building code of Finland? The bulletin says directly: “As legislation changes along the course of history and is subject to political decision-making, legislation can sometimes contradict the otherwise motivated ethical principles. Occasionally, legislation can allow ethically questionable activities (loopholes) and, at times, it can even oblige this kind of action.”

The bulletin states that architecture is a constructivist field. Architects should not take information as granted from other fields of expertise, but they must create it by themselves, set it against prior knowledge and the values in their field.

At its most simple, sustainable development can be defined this way: an activity is sustainable when it can be indefinitely repeated, without harming anyone or anything. It could be said that the fundamental idea of sustainability is the same as that of an open wilderness hut – leave the place in the condition it was when you arrived.

This definition of sustainability can be adopted as such to building design. Consequently, sustainable construction is represented by activities where there is first discussion as to whether it is necessary to construct a given building in the first place. If it is, harmless materials and simple structures that are easy to maintain should be used. The key questions are as follows: where do materials come from, where do they go, and in what time – and whether this can be indefinitely repeated.2

We architects have the sort of prior knowledge from our field that allows us to put all these things into perspective. We have accumulated knowledge regarding which structures are the most tried and tested and have proven to be harmless in Finnish conditions. I wrote “which structures are the most tried and tested” and not “which structures are the oldest”, as our field is progressive, even evolutionistic: architects are not eager to learn from the past, but rather “old” and “new” matters within construction are kept in separate sections. In the discipline of architecture, the most tried and tested buildings are perceived as historical buildings and therefore, they are presented in history books and not in building technology books. Although our entire building stock is present today, we tend to think that tried and tested buildings belong to some other era that cannot recur – even though it would be easy to refine this timeless way of construction by applying modern methods.

The architect looks at the construction site and stops. After pondering a while, she understands that if she does not act, no-one else will do it on her behalf: it is the architect who is able to influence the problems of construction at their origin. The architect realises that she does not have to do just about anything for money. The architect understands that although she is in a difficult, inherited situation, she does not have to repeat the mistakes of the previous generation. ↙

LARS-ERIK MATTILA is a carpenter and architect.

The rendering of the illustrations for the present article has been supported by the Finnish Cultural Foundation. The text has been compiled by Anu Lahtinen, publishing editor, based on a script by Lars-Erik Mattila.

1 These three problems have originally been formulated by technology expert Kris De Decker, in his article ”How Circular is the Circular Economy?”, Low Tech Magazine 3/2018. www.solar.lowtechmagazine.com/2018/11/how-circular-is-the-circular-economy.html

2 I summarised these fundamental questions regarding construction together with architect Ransu Helenius.