Published in 2/2019 - Education and Research

Should Collectives Replace Starchitects?

Increasingly high expectations are being placed on the societal significance of an architect’s work. The contemporary notion of the architect as an idealist is not, however, a solely positive development if it doesn’t rethink the structural dimension of architectural production and work.

During recent years, the professional image of an architect has been at a major turning point. With various exhibitions, publications, educational programmes and collectives, a new perspective has emerged on the production of architecture and the social and societal responsibility of architects in curbing climate change, for example. On the other hand, the more traditional educational frameworks and means of conceptualisation that emphasise individual creativity are still going surprisingly strong. Although few in the field are talking explicitly about architectural maestros anymore, the media coverage of awards and architectural competitions is often personified in the main partners of architectural firms or rising young talents with exceptional potential. What happens when these very different perspectives collide in the discussion regarding the role of architects in society?

A more societal and political approach to architecture has been called for especially by architectural theorist and pedagogue Jeremy Till, whose polemic (self-)criticism of the current state of architecture, Architecture Depends published in 2009, raised debate particularly among the architectural profession of Great Britain.

A long-term faculty member of the sociologically focused School of Architecture at the University of Sheffield, Till emphatically disassociates himself from the perspectives highlighting the autonomy of architecture, according to which an architect is considered to remain above any societal discord. As claimed by the autonomic tradition, an architect must be allowed sufficient aesthetic freedom in relation to society and politics, or the consequence is invariably some kind of aesthetic compromise. The roots of this tradition span from the classical 19th-century Beaux-Arts teaching method to the 1970s discussion on architectural autonomy, in which the teachers were regarded as a type of older-generation guardians of deeper knowledge and thinking.

Although few in the field are talking explicitly about architectural maestros anymore, the media coverage of awards and architectural competitions is often personified in the main partners of architectural firms or rising young talents.

In the autonomic tradition, the stereotypical, often male architect has a deep sensitivity to nature and an ability to see beyond social conflicts and political interests. At the same time, the definition manages to exclude anyone who does not fit the mould, as pointed out by, for instance, Despina Stratigakos’ pamphlet Where Are the Women Architects? (2016). By polemicizing about how such often unconscious base assumptions guide architectural education and practice, as well as the representations produced thereof, Till can be considered to have anticipated a later, wider discussion.

The deconstruction of the genius myth that maintains the artist’s autonomy is one of the hottest current cultural-political issues. The #metoo discussion, for example, has brought to light the ways in which many social evils and even authoritarian features related to artistic work and art education are justified by mystifying various fields of art as having a unique and special character, and thereby deserving complete autonomy. However, citing the creative, exceptional individual as a justification is rarely done explicitly today. The autonomy myth is communicated rather through the representation of the starchitect – the celebrity architect that is so often seen in the media.

The starchitect ideal

The architects who have received ample media attention over the last few decades, such as Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, as well as Patrick Schumacher who is currently running Hadid’s firm, can be construed as proof of the concept that exceptionally fascinating architecture is still chiefly produced by exceptionally fascinating, creative individuals. They are not shackled by too strict public planning and building regulations, for example.

In his book The Architecture of Neoliberalism (2016), English architectural theorist Douglas Spencer suggests that such a conception of autonomy is principally a product of the neoliberal era: architecture must remain free of social obligations for the sake of not only architecture itself but also of society at large, for the free market is, according to neoliberalism, what determines the social balance. It is therefore within the interest of society to allow complete artistic licence for exceptionally creative individuals.

This idea has also been adopted by Patrik Schumacher, who has suggested that architecture, urban planning and housing production should be left entirely up to the market. According to Schumacher, this would guarantee not only higher-quality planning but also planning that better meets the common shared interest: for instance, housing prices would be determined by the market, which is currently prevented by, according to him, artificial public regulation.

Like Schumacher, Danish-born Bjarke Ingels, who is perhaps today’s most talked-about architect, is a good example of how the autonomy of architecture is justified in the neoliberal context by citing the common good. On the face of it, the BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) firm led by Ingels seems to depart from certain elitist features associated with the starchitect representation. For instance, the firm does not scorn housing projects or downplay architecture’s responsibility in social and ecological problems. Indeed, on the flipside of the shiny starchitecture aesthetics are invariably questions relating to, for example, how architecture can be employed to meet the challenges of climate change or to make public spaces more human-oriented and engaging.

Is Ingels not identified, then, more as an idealist than the kind of authoritarian genius that the starchitects rising from the autonomy tradition, such as Frank Gehry, are often described as? In a way, the answer is yes, but in precisely this contradiction lies one of the reasons behind Ingels’s success. In the current economy, value is created not through the manufacture of goods but through innovation and design. It is necessary for this kind of value creation to also engage in continuous demarcation with perspectives that are typically completely opposite to those of the economy, such as counterculture and a criticism of capitalism.

Whether we are talking about a Silicon Valley start-up or a socially critical artist, success is based on how adept one is at balancing between economic growth and criticism directed at it. This is exactly where Ingels has succeeded, as the Big Time (2017) documentary by Kaspar Astrup Schröder, for example, demonstrates. The documentary follows Ingels’s work in the cross-pressure of conflicting objectives. Ingels is seen attending the Burning Man cult festival and advocating cycling and communal spaces, all the while winning the most significant competitions for new skyscrapers in Manhattan and expanding his firm into a global giant. The documentary shows Ingels going in for a brain MRI due to headaches, which luckily does not reveal anything seriously wrong. However, this detail offers the opportunity to indulge in a clichéd reflection of whether even the structure of an exceptionally creative individual’s brain has to show signs of exceptional genius.

Ingels seems to be an updated version of an architectural genius – an exceptionally creative individual who both follows in the footsteps of the great masters and dabbles in counterculture. An exceptional individual can be both an idealist with ethical and ecological interests and, simultaneously, involved in designing the world’s first Hyperloop rail system, with nearly six-fold travelling speeds compared to contemporary trains, between the cities of Dubai and Abu Dhabi that seem to stop at nothing in their pursuit of growth.

The architect as a worker

Even though the autonomy of architecture is no longer defended explicitly, it still makes its presence known as the unspoken idea that architecture is, at its core, about a higher creative vocation and calling than mere labour. The attention received by Ingels is a good example of this mindset.

Yale University Professor of Architecture Peggy Deamer has sought to politicise architectural education, research and practice and has brought attention to the problematics related to the definition. The Architect as Worker: Immaterial Labor, the Creative Class, and the Politics of Design (2015) edited by Deamer is an ambitious attempt to redefine the education and work of an architect by visualising the precarisation entailed in these, i.e. the general uncertainty and the increasing psychological burden of working life. Although the concept of precarisation has been discussed in several other fields almost ad nauseam – with the information, art and culture industries in particular – a similar discussion in architecture is, according to Deamer, still in its embryonic stage.

What is it that has made the architectural discourse, at least in the United States, downplay the growing precarisation? It is precisely the new forms of the genius myth, exemplified by Ingels, that are playing a part in nourishing the idea of architecture as something better and nobler than labour. Deamer suggests that in education, this is especially seen as an emphasis on entrepreneurship: it is viewed as a means to fulfil oneself and define one’s own objectives, instead of “just” working for someone else. There is naturally nothing wrong with going into business, but for many it does not only represent the freedom to fulfil oneself like Ingels, but also longer hours, uncertain income and poorer welfare benefits.

Together with her colleagues and students, Deamer established the organisation Architecture Lobby in 2013, tasked with bringing to light and addressing the downsides and injustices of the architecture industry. These include, among other evils, unpaid internships and overtime, an unhealthy competition within the industry, as well as ballooning student loans. Architecture Lobby is not, however, merely an industry interest group, as the operations also challenge the preconceptions often assigned to the gender, social class or ethnic background of architects and demonstrates how they can be deconstructed, as the organisation’s social media hashtag #endpatriarchitecture suggests.

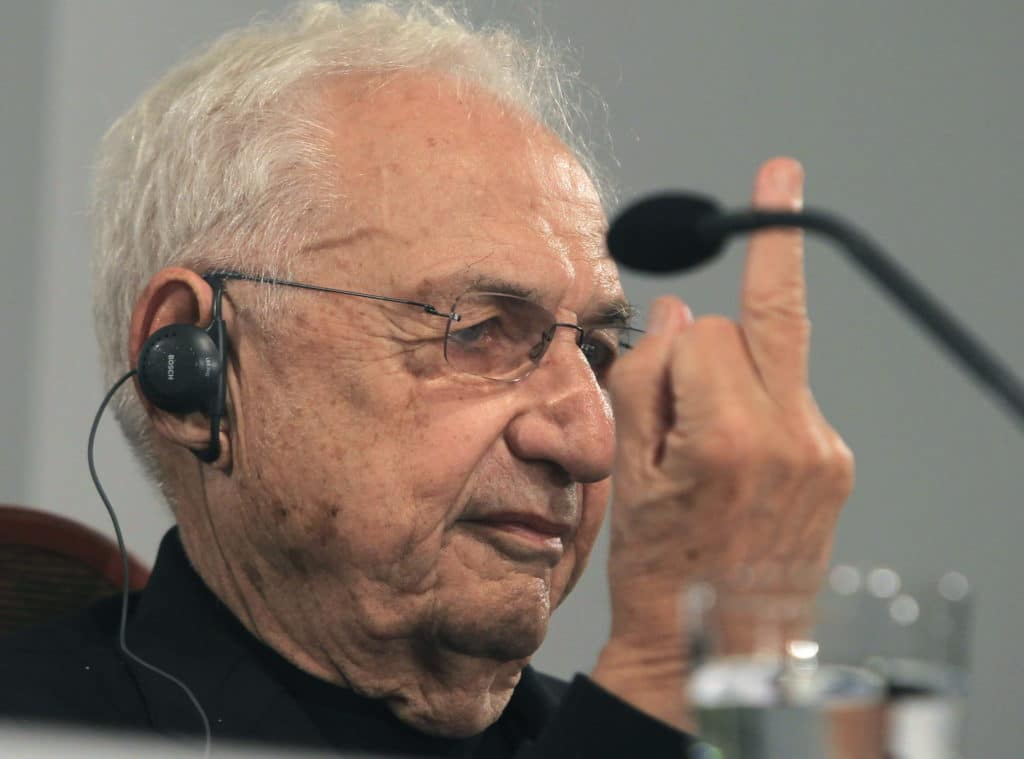

Visualising the definition of an architect’s work and the flaws of the industry is also associated with the architect’s relationship to the other areas of work related to architecture, with construction work and workers in particular. Designing and building have typically been strictly separated. The situation has been made even more troublesome as this division has adopted a global dimension. The actual construction work may be conducted under completely different labour laws to the design process, which has, in the most extreme cases, led to arrogant comments such as those made by Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry about how they, as designers, are powerless to do anything about the working conditions at the construction sites for the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim Museum or Qatari football stadiums.

The understanding of the multitude of different labour inputs entailed in architecture from the design process to the finished building is, however, clearly becoming more multidimensional – for example, organisations and actors like Who Builds Your Architecture, the Human Rights Watch for Architects, Architecture Sans Frontières and the GULF (Gulf Labor Artist Coalition) constitute a new type of an attempt at developing solidarity between construction workers and designers.

Collectives as the solution?

An essential and probably one of the most well-recognised attempts to rethink the status of architecture in society is associated with the transition from individuals to collectives. Several architecture collectives that have received a great deal of attention in recent years, such as the Assembly in Great Britain, the Raumlabor in Germany, the AAA (Atelier d’architecture autogérée) in France and Uusi Kaupunki in Finland, are showing us how economic and ecological crises also force those working within architecture to reconsider the operations and values of the field.

The Social (Re)Production of Architecture: Politics, Values and Actions in Contemporary Practice (2017), edited by Doina Petrescu and Kim Trogal working at the Sheffield School of Architecture, provides a fascinating outline of architecture arising from collectiveness and collaboration, i.e. commoning. The book focuses on the question of how the production of architecture could be built chiefly upon societal or social objectives.

Tatjana Schneider has studied critical architecture groups and spatial practices and suggests that the notion of social production can be applied to the architectural practises and activism at the grass roots level – she calls them expanded architectural practices – that have come to light during recent years. For example, various temporary constructions, squatting, as well as places, spaces and spontaneous activities shared by a community generate both economic and architectural value that is difficult to measure directly. They entail social, humane values and objectives from a wider perspective than the mainstream production of architecture.

Architectural collectives that aim to make the world a better place are often perceived as a recreational interest that one engages in outside one’s full-time job.

This type of a wider understanding of the means of producing architecture is not, however, without its problems. For example, several trends of activism that declare everything that happens within the urban space to be of equal value may also disregard the architects’ expertise in issues that require specialised knowhow. Therefore, there is still a market for professional practice, even if designing and planning were to be partially based on non-hierarchical crowdsourcing. On the other hand, despite sincere intentions, many of the ethically inclined architectural interventions directed at developing countries and collective activities with the local community can never be completely free of power play and hierarchies, as demonstrated by the so-called white saviour phenomenon.

Instead of the professed revolutionary nature of collectives, the issue is perhaps more structural. Architectural collectives that aim to make the world a better place are often perceived as a recreational interest that one engages in outside one’s full-time job. Architects have to work in construction projects that they regard as problematic in order to be able to act critically in their spare time. They must compete against each other, first at school and later at jobs, in order to be able to form collectives and peer learning spaces free from hierarchy in their free time. They have to travel to developing countries in order to gain ethical meaning for their work. That is why we need new concepts, movements and practices that will completely rethink the relationship of architectural education and practice with the society surrounding them. ↙

Aleksi Lohtaja (b. 1990, M.Soc.Sci) is doctoral student at the University of Jyväskylä. His research interests include the political dimension of architecture, utopias, and the cultural policy of creative labour.