Published in 6/2004 - spaces for knowledge, Pietilä

Pietiläs’ Other Half

Aino Niskanen interviewed Raili Pietilä in autumn 2002. The interview began during a lecture trip to the United States and was brought to a conclusion at Raili Pietilä’s home in Helsinki.

The apartment is big and old; the kitchen table is often the place where people gather. In the living room there are furniture prototypes, many rocking chairs, textiles from India, naivist and abstract art, and animal figures made of fabric and wood; an archetypal or symbolic animal is often present in Reima Pietilä’s ‘pictorial essays’.

Raili Paatelainen was born in Pieksämäki in 1926. Her path converged with that of Reima Pietilä (1923–93) in their years as architectural students and this resulted in a cooperation and dialogue that lasted for many decades. They founded their joint office in 1962.

Early recollections

Raili Pietilä describes her husband’s early years, “Reima’s mother had been foretold that her son would be an architect and her daughter an artist. The predictions came true. Reima inherited from both his mother and his father an ability for working with his hands. Reima’s parents had bought a small place by the sea, and Reima’s mother designed a summer cottage there. Mother drew plans at the kitchen table and watched from there as Reima and his father built.”

Reima made international contacts early in life. He had learned the rudiments of English from his parents, who had been in America. Reima’s mother went to Vancouver, Canada, in 1912 as a servant and then moved to Seattle in the United States. There she met her future husband, Frans Pietilä, who worked as a lumberjack and a slaughterhouse worker. Ida Pietilä returned with her firstborn, Tuulikki, to Finland in 1920, and Frans followed soon after. Reima was born in Turku in 1923.

When Reima came to Helsinki to study, he turned the whole flat into a studio, with large plaster sculptures – he was always busy. “Reima was interested in everything, including modern music. A Stockhausen performance was something that he enjoyed. And natural forms were so wonderfully free – and the sounds of nature. Reima always had some ‘handwork’ (reading) with him; he would study, add notes and dog ears to books and magazines.”

In his student years Reima had many contacts with young foreign architects working in Helsinki, especially Swiss and Germans. Early on, he joined CIAM and attended the group’s meetings. The members of CIAM became long-time friends, Aldo van Eyck and Georges Candilis, for example.

Dipoli and Suvikumpu

The Pietiläs first joint work was Dipoli. “Dipoli was an exciting and wonderful project, which generated new ideas all the time, although there were many great ideas that could not eventually be realised.” The debate concerning the publication of Dipoli in the Finnish Architectural Review was a difficult experience for the Pietiläs. Later they wondered why architectural students and architects were so unwilling to understand or accept Dipoli.

Dipoli and the Suvikumpu apartment buildings are close together in time and have common features. The facades of Suvikumpu had a texture of concrete formwork boarding that was timber in the Dipoli building. Young colleagues reproached them that it showed a lack of integrity when timber and concrete looked the same. The Pietiläs in turn pondered why concrete should be painted grey or black, which was the trend then; why not use a greenish tone and introduce a new colour component to the building?

Christian Norberg-Schulz was one of those three whose critique of Dipoli in the Finnish Architectural Review was positive. When writing the critique, he had not seen Dipoli completed, but he had followed its design since the competition. Norberg-Schulz became a friend, as did John Hejduk and Malcolm Quantrill somewhat later; Quantrill’s wife was Finnish.

When the plans for Suvikumpu were more or less finalised and the site ready for the project to start, the Pietiläs left for St. Louis, where Reima had been invited to take up a professorship for the autumn term of 1966. Today St. Louis is a more peaceful city, but at that time the Vietnam War had repercussions on campus, and sometimes it was even a bit scary.

“When Annukka [their two-year-old daughter] and I went to see Reima at the school, a military patrol was present every day, inspecting all the premises every two hours or so. Posters saying ‘Make Love not War’ hung everywhere, side by side with others asking student to volunteer for Vietnam.”

Exhibitions and work in Kuwait

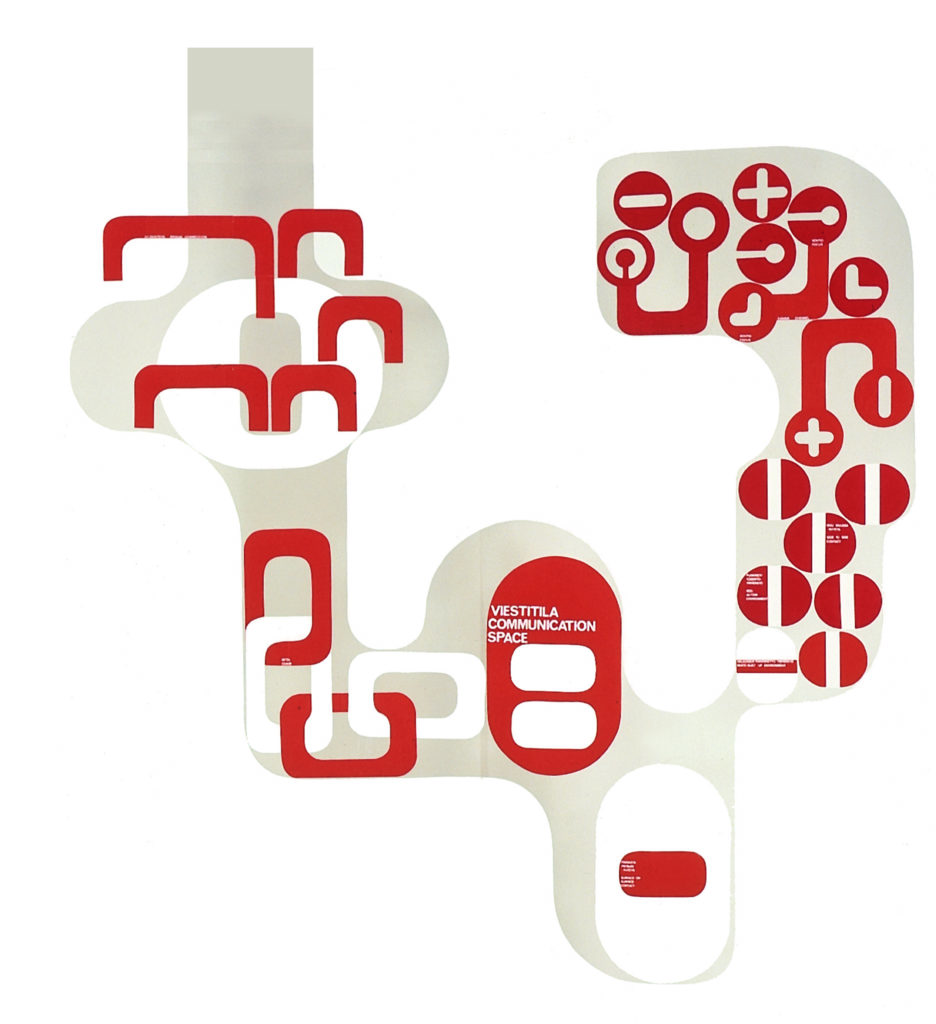

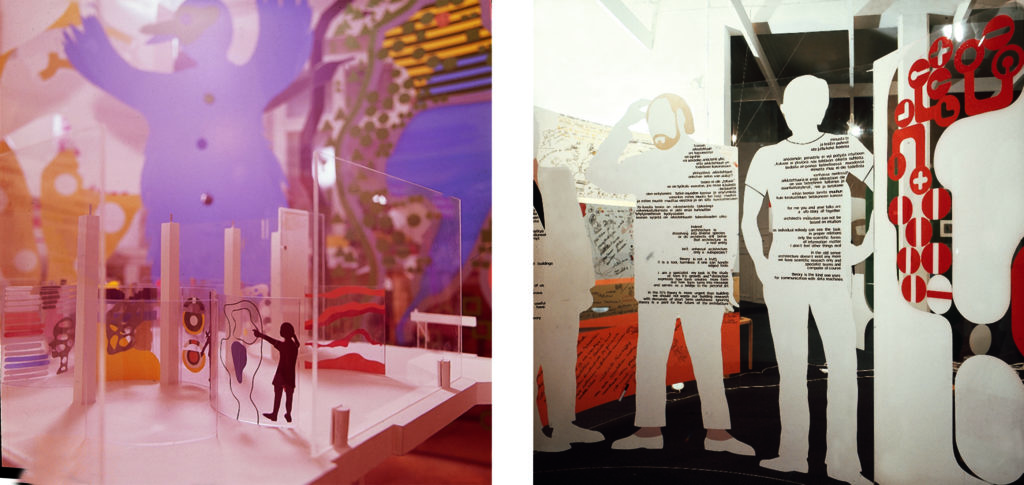

The Pietiläs worked on exhibitions together. “It was fun. At the time we had no work. Reima was doing exhibition sketches on a piece of paper and we thought, what the heck, let’s just do it.”

The Zone exhibition was held just before the Christmas of 1968 at their home on Korkeavuorenkatu, where drawings on long pieces of paper were hung in the four-metre-high rooms. “It was probably the most peaceful place in Helsinki. It was like a Christmas street, with faint music in the background, and the pictures.”

Raili worked in the Helsinki City Public Works department and supported the family. Some twelve years passed from their successes in the Dipoli and Suvikumpu competitions before they won another major project in Finland. “Reima thought that it was actually quite OK, as he was writing and thinking of new buildings, and you can always think and sketch.”

One day in 1970 an offer of work arrived. “When I got home a bit before four, I would always ask about the mail. One day Reima brought a telegram over half a metre in length; it was from Kuwait. It asked whether we were interested in coming to London to discuss a possible design project in Kuwait. We checked on the map where Kuwait was.”

The idea for inviting the Pietiläs came from Sir Leslie Martin, who had visited Finland and seen Dipoli. The idea of commissioning international architectural practices to put forward ideas for the master plan of the capital had sprung up in Kuwait. In London the Pietiläs met the clients and other invited designers: Candilis, the Smithsons and the Italian architect, Belgiojoso, of the BPR partnership (Belgiojoso – Piano – Rogers).

The Pietilä’s left for Kuwait before Christmas. What they saw there was a former fishing village that had ballooned into a big city, and more Bedouins were moving in across the border every night. At the end of June the Pietiläs sent plans, a model and a report to Kuwait. In autumn the participants were invited to London again. There they heard that all the participants were to be given a project for further development. The Pietiläs continued with the buildings of the Council of Ministers by the shore. The work continued through the entire 1970s and was completed in 1982.

“The Kuwaitis were very strict with their instructions. They gave clear criticism when something was unsuitable, or they could be enthusiastic about an idea and say this part is OK, but that area needs amending, as a teacher might say to a student.”

Reima received a professorship in Oulu, in 1973. “Reima was a born teacher. He would always be happy when a foreign student appeared behind his door with a question. Reima would be enthusiastic – Aha! – and the whole day would be spent discussing the question. He welcomed teaching in Oulu. Reima thought that you should mark out your territory during school years, do what you are interested in and ‘you should not to take for granted everything you are taught’. The teaching in Oulu lasted for five, six years. Then Reima grew a bit tired of it. We did actually have a lot to do with the Kuwait project, and Reima said that the teacher ‘had now learned what he set out to learn’.”

Managing the office and competitions

“The office was always somehow linked with home, and the number of employees varied from ‘a half to forty’. When the office was at its biggest, Reima went there reluctantly, he would sigh and say, ‘I don’t even know all of them, what will I say to them?’

“Reima spoke about setting traps: he would put questions to himself, for example, on something that he had seen, let’s say a project in the Finnish Architectural Review, where something had stuck in his mind. Why had the architect solved a problem in a particular way, why not in such or such a way? The problems could be theoretical too: ‘Why so? Why not that way? What would happen if I placed something here and another thing there and drew a line between them – what would happen?’ In other words he would during the course of the day set these traps, snares, and would then say that ‘I am laying a few traps.’ When he would envisage the same picture a few days later, there he would find an answer to what had puzzled him, waiting.”

For example, Reima and Raili drew Dipoli to quite a large extent on their own, and the assistants only came into the project at a fairly late stage. Few projects started so that the office would just start planning on receiving a commission. Many projects started from successful competition entries that were first carried out by the couple themselves. The realised projects proved to be extremely laborious. There was a lot of elbow grease required, for example, the working hours for the presidential residence, Mäntyniemi, exceeded 84,000.

“Luckily it was possible in those days to prepare competition entries in a fairly home-spun fashion, unlike today. Sometimes competitions would be started, but if there did not seem to be a comprehensive enough concept or idea, the plan was not finished. Competitions were executed with minimum staff. So if you won a competition it was something of a windfall as no great input was involved in it.”

Sometimes the formal concepts of competition entries would pass into the next projects. “Forms that you were not yet able to erase from your mind come to the fore. Then they just whirled around, crowding each other out. Reima’s opinion was that wild, theoretical attempts are quite appropriate in competitions. Competition entries can be largely based on theory, as you never know what the result will be. Since it is very uncertain that you will win a competition and you don’t know whether it will ever be implemented, you can throw in some bolder ideas. When we started on a project or a competition, Reima used to say ‘Let’s see if this theory works’. Competition entries were intentionally done away from the everyday environment, often during summer holidays. It was dictated by necessity, as the home and the office were in the same building and there were a lot of people in the office. Sometimes when you had a problem to solve there was no option but to take a return train ticket to Hämeenlinna or Tampere and be away for the duration of the journey. There we’d talk about the project.”

Competitions were often associated with a specific atmosphere. “I remember some time towards the latter part of the Kuwait project we were draughting the Dubai Deira competition, which we found interesting. At that time the apartment happened to be quite empty and we had a tent in the middle of the room. Our daughter Annukka was small, and it was a kind of a game, a place where she could play. We would have this yellow tent, drink coffee or take an afternoon nap there. Annukka enjoyed it, and Reima would tell her stories. It was an exciting place.”

Play and fantasy seem to have been present in the working atmosphere in other ways too. “There has always existed, as an inherent part of me, a playful person, so that all these ideas that came from Reima soon felt very familiar to me.”

Combining images and words into some kind of pictorial-literary poems was for Reima a way of making notes on his thoughts, to draw and to write on the drawing: ‘A direct link from the head to the fingertips’, he would say. Did Reima’s way of sketching and designing seem peculiar or different at the beginning?

“Well, it was strange, but I had already got to know Reima in his student years. Everybody said then that you can’t make head or tail of what he says. But to me the obscurity was so clear that it was strangely soothing.”

Finnish Embassy in India

The competition for the embassy in New Delhi was won in 1963. Raili remembers that they did the competition entry drawings by Lake Päijänne, where the scenery in the Korpilahti area is rather imposing. “You didn’t have to do more than squint your eyes and imagine that there are mountains here, the Himalayas just nearby. But when we went to India, we talked about how in winter the lakeside view is a long open stretch to the northeast where winds and dry snow blow in forming ridges of snow. When you look at such a view it is like mountains. It became one of the starting points; the pseudonym was ‘Snow speaks on the mountains’.”

The New Delhi commission slipped through their fingers and went to the entry that was awarded second prize, Lauri Silvennoinen’s work, which was based on prefabricated components. Silvennoinen’s project, however, was never begun as he died in 1967. The project was frozen for a long time, until at last in the early 1980s the Pietiläs were awarded the commission. The design changed from their competition entry, as the Indian officials would not accept a building under one roof. In India they used to take the population count by taking an overhead photograph from an aeroplane, calculating the number of roofs in the picture and multiplying that by a certain coefficient, since it was accepted that every nook and cranny of a building would be inhabited. And even when we sent an officer from the National Board of Public Building to explain the project, it had to be divided up into separate parts.”

Memories of the building site in India. “Well, it was absolutely wonderful. I have sometimes told the story while showing pictures, that the Tampere Main Library and Delhi projects coincided, and while in Tampere there were 60 builders on the site, in Delhi there were over 600. The local contractor had agreed with a nearby village that the villagers would build the embassy and had reserved a fenced off area for them on the site. The villagers came there to live with their families, children and all.”

President’s official residence

“The official residence of the President is a tool in the President’s hand. State visitors come there and you need a Finnish building to show them. It has to be made of Finnish materials and has to be in a way ‘Made in Finland’. The project Kiillemoreeni (Mica Moraine) was sketched out at Hankasalmi, in central Finland, in the same manner as Delhi was sketched out by Lake Päijänne. They both contained themes from the Finnish Lake District at the outset, mental images of the Ice Age forming the Finnish landscape – how the layer of ice, slowly moving from southeast to northwest, moulded the terrain to certain forms. Ice dragged along with it a lot of rock material and ground it into sand and larger blocks, then simply deposited them and melted away. This is the origin of moraine soil.”

The President’s official residence was lavishly publicised in the Finnish Architectural Review. It was praised, but also met criticism from within the profession. Was the criticism hard to take? “Generally that kind of design project is difficult in many ways. There are schedules, compromises and other pressures. Then there was criticism from colleagues that it isn’t a house at all, it’s a vodka bottle designed by Wirkkala. But at the time, work schedules and finances were so tight that there was no chance to mull it over or respond to it. Also the client, that is the National Board of Building and the Office of the President of the Republic, took the stand that we need not respond to criticism in the press, and that it was not advisable either. It was an enjoyable job as such. We were allowed to work in peace, at least to some extent.” ↙